The current coronavirus pandemic has brought home to us all how fragile human health can be and also how our lifestyles and assumptions can be completely disrupted by an event of this type.

Dorset History Centre holds over 1,000 years of records relating to our county and we thought that it would be appropriate to consider how a previous era coped in an era of extreme stress and turbulence linked to the outbreak of a previously unknown disease.

To do this, we asked recent DHC employee Dr Mark Forrest, an expert on the Black Death, to provide us with an overview of how Dorset coped with a pandemic situation nearly 700 years ago…

—

In 1348 two ships … landed at Melcombe in Dorset a little before Midsummer. In them were sailors … infected with an unheard of epidemic illness called pestilence. They infected the men of Melcombe, who were the first to be infected in England. The first inhabitants to die from the illness of pestilence did so on the Eve of St John the Baptist [23 June], after being ill for three days at most.

Chronicle of the Fransiscan Friars at King’s Lynn

When the plague arrived in Dorset in 1348 it was a new and unexpected crisis, rather like the arrival of Covid-19. At the time it was called the pestilence and nobody knew where it had come from, how it spread and how it might be cured. Now we know it was the pathogen yersina pestis, commonly called the bubonic plague, which still periodically jumps the species barrier from rodents to humans in places as far afield as China, India, Peru, the western United States and Madagascar. Although the plague is easily cured with antibiotics it still kills around a hundred people each year in remote areas.

When it arrived in Dorset in 1348 the plague spread quickly, along the coast and up the river valleys. Its progress may be plotted by the appointments of extraordinary numbers of parish priests to replace those who had died. During the month of November the bishop in Salisbury appointed new priests on twenty-two different days: for parishioners who could not cure their bodies the cure of their souls was the most important concern.

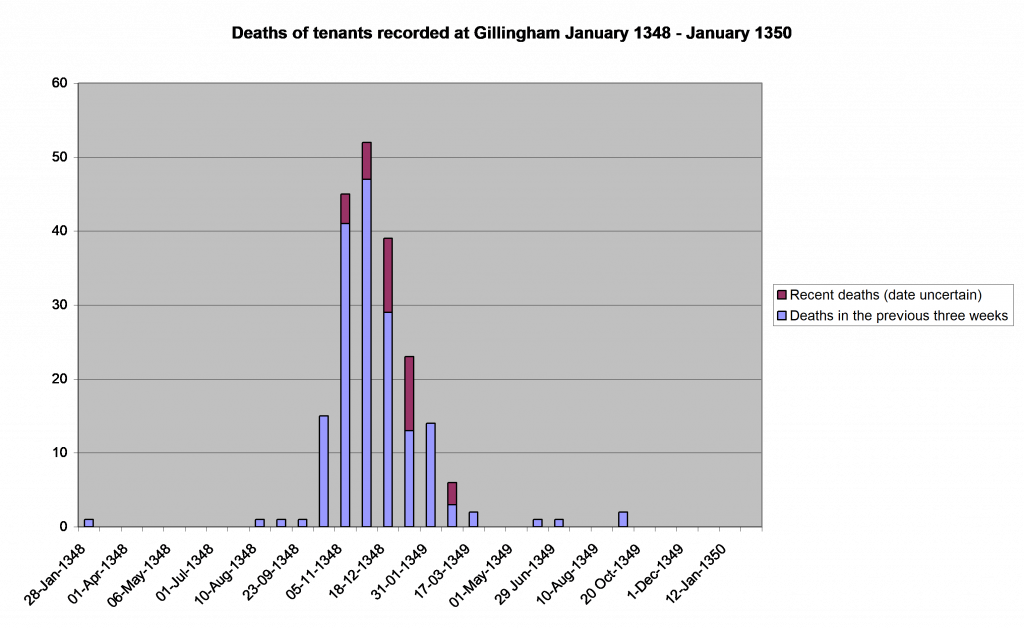

Going to church attendance did not help to flatten the curve. Nor did the attendance of heads of household at the regular three weekly manor court; the medieval equivalent of a parish council meeting. At these courts the lord of the manor’s steward recorded the deaths of his tenants, their heriots (death duties) and the new tenant who took over their property. At Gillingham in north Dorset there is a particularly good set of manor court records and recording that around 140 of the 300 tenants died during the outbreak, with a further twenty deaths among the new tenants. The deaths began in October 1348, reached a sharp peak between November and January 1349 and had returned to normal levels by the end of March.

The Gillingham community held together, they were lucky that several of the steward, bailiff and a couple of older tenants survived to provide leadership. But the plague returned again thirteen years later and fresh outbreaks every ten or twenty years meant that the population levels never recovered. Across Dorset labour intensive arable farming gave way to an increase in the number of sheep.

Throughout its history Dorset has suffered from outbreaks of diseases such as plague, typhoid, cholera and tuberculosis. Most have left traces in the parish and borough records of individual communities. Plague years and outbreaks of other diseases such as cholera can be identified by increased numbers of deaths in the parish registers. The development of public responses such as the introduction of quarantine periods can be found in the court records.

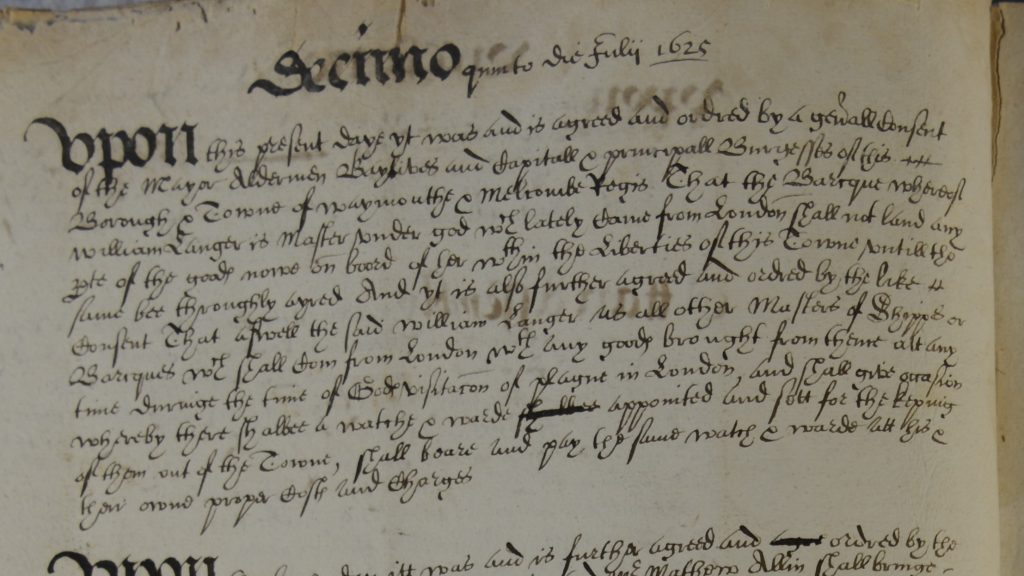

Upon this present day it was and is agreed and ordered by a general consent of mayor, aldermen, bailiffs and capital and principal burgesses of this borough and town of Waymouthe and Malcomb Regis that the barque whereof William Langer is master under God which lately came from London shall not land any part of the goods now on board of her within the liberties of this town until the same be thoroughly aired and it is also further agreed and ordered by the like consent that as well the said William Langer as all other masters of ships, barques which shall come from London with any goods brought from thence at any time during the time of God’s visitation of plague in London and shall give occasion whereby by there shall be a watch and ward appointed and set for the keeping of them out of the town, shall bear and pay the same watch and ward at his and their own proper costs and charges.

—

An article on the Black Death in Dorset, by Dr Mark Forrest, focusing on the bishop’s registers and Gillingham manor appeared in the Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society, volume 131, 2010, together with articles on Edward Jenner and Dorset’s role in early vaccination, Henry Moule and the prevention of cholera in Fordington and the development of public sanitation infrastructure.

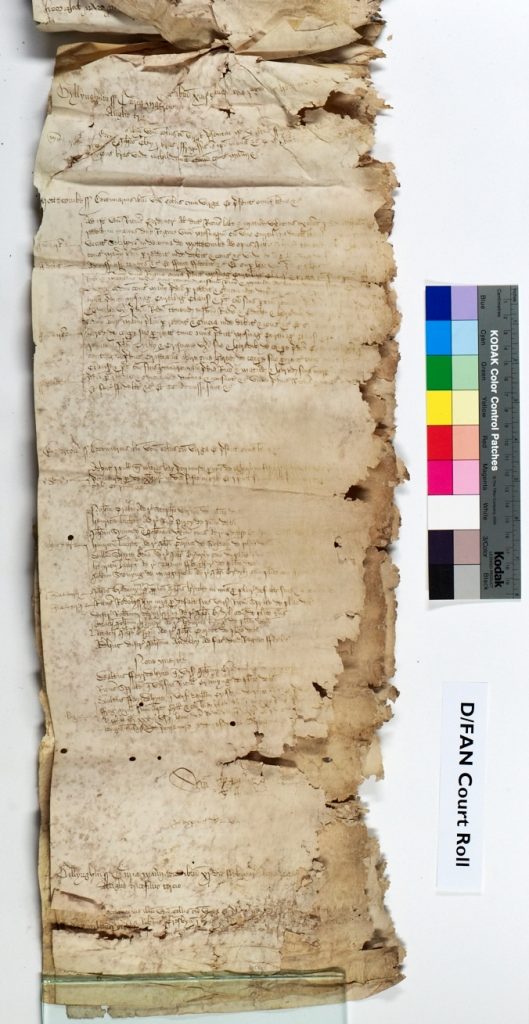

Gillingham manor court roll

Of the surviving records am I able view the details say from 1600 onwards preferably translated. If encompassed in a book then perhaps you would pass on the details.

I am unable to travel to DHC

Thank-you for your comment. Unfortunately, there are no transcribed sections of the Gillingham Court rolls and there are none in progress as far as we are aware. We know that someone is working on analysing some of the data from the medieval rolls, but not transcribing them. If you are just interested in post-medieval Gillingham, we recommend John Porter’s book ‘Gillingham: the making of a market town‘, which should be available online!

I have studied the Plague epidemic of 1348 for years, Current research by Marseilles University seems to indicate that the parasite that spread the disease between family members was human fleas and especially human lice, that resided in the straw bedding the family slept in. The other point I would like to make is that Black Ship rat, Rattus Rattus, is a creature of habit that would not stray far from the port in which it found itself, and furthermore, the plague would stay within the rat population until there were no rats left. The Xenopsylla Cheopsis, the rat flea, for preference will choose rats over any other animal. If the local rat population all die of plague, and the infected and blocked rat fleas would then bite humans that went to the ports to collect goods. They could also find themselves in materials collected from ports and taken back to villages. That would help infect other local rat populations and could well infect other animals – with the exception of horses – as well, helping spread. However, given the mini iceage that happened around the time of the Plague, I doubt there would have been massive rat populations to begin with, even with all the filth that existed at the time. The fact that the highest death rates in North Dorset took place during the winter months primarily, does suggest that the work undertaken by Marseilles University into the mechanics of the spread of the 1348 Plague is correct. The primary vector were human fleas and lice and not rat fleas subsequent to the human first flea bites at ports and a few that were in material.

Hi from the local village historian and the local landowner I understand there was a Manor House on burnt house bottom fields on Alton Pancras. This was burned down due to the presence of the Black Death coming from Weymouth as one of the captains of the ships was a friend of the estate owner and visited him in Alton Pancras Manor House . There appears to be no mention of this occurrence in the historical records. The landowner did some excavations some years ago but could find no remains of the Manor House on the site. I further understand that there were cottages on each side of the roadway up to the Manor House that were burned also !

Is anyone aware of these matters which I presume have been handed down to the village elders over the years and is still being repeated.

I have looked for any drawings of the manor to no avail as did the estate owner in his time . Now deceased. But there are definite singles of cultivation on the field and tiered levels suggesting there were people living on the site.

Hi Rodney – thanks for your message. Your query has been passed onto one of the team here to have a look into, and we will be in touch by email in due course with any information we are able to find.