‘…I have scrawled with my pencil a sort of view…’

—

In recent times, and particularly during this period, our means of communication has become largely ephemeral and digital; including text messaging, video and audio. But for centuries it was not so. Until the advent of the telephone in the latter part of the 19th century written communication was the only option unless you could speak to someone face to face. As a result, correspondence in the form of letters, notes and later telegrams and postcards feature in many archive collections.

From the medieval period legal and official correspondence was being penned often by paid clerks as even many of the gentry were illiterate. Following the Reformation, the importance of the ability to read the Bible and with it the ability to write grew as did letters of a more personal nature. Many collections relating to landed families contain correspondence between family members describing relationships, personal, local and national events and much more. As many of the landed classes were also involved in politics there are letters relating to national and local political events as well as the administration of their estates and their tenants.

The impact of war is strongly represented in letters, including in this one, written home from America by an emigrant from Dorset in 1864;

This dreadful war still drags its tedious course, and people are becoming hardened to its details of horror. But we hope and trust for a happy issue, even if it should please a kind and overruling Providence, that with still prolonged judgement the curse of slavery must be rooted out from among us.

The whole country is in mourning and the best and noblest of the land are in the army.

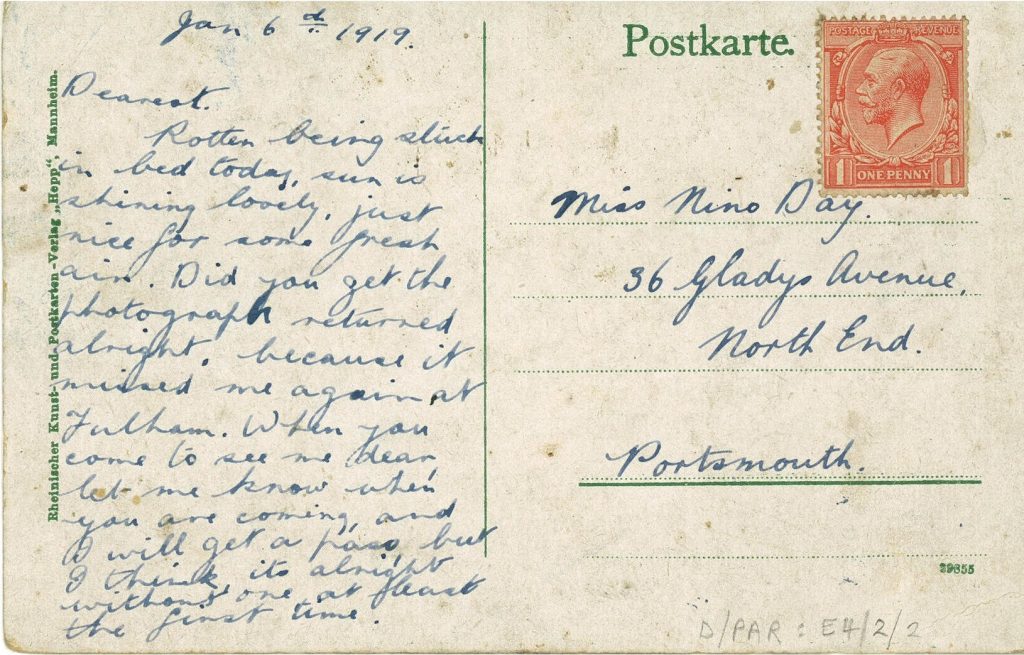

The voice of ‘ordinary’ people is missing from most records until the growth in literacy during the 19th century. Letters can be long or short, in some cases little more than scribbled notes which in some situations became more formalised; either as postcards of the ‘wish you were here’ variety to postcards from prisoners of war in Germany during the First World War.

—

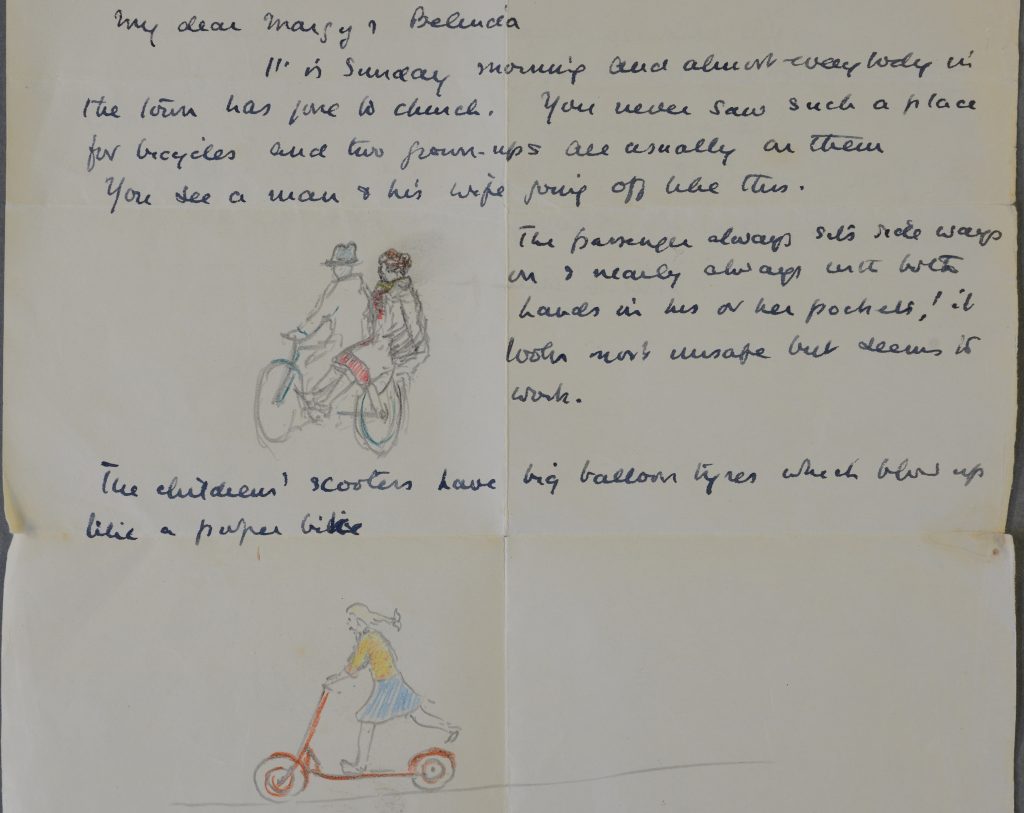

In fact, every letter writer reveals their own ‘view’ of the world, their daily preoccupations, their humour and their values. The following extract from a sweet letter is from Jack Parham (General) to his daughter Belinda during his service in the Second World War;

I went for a lovely walk late at night over Salisbury Plan; it is a lovely great place miles and miles and miles of grass, no fences and a few little woods about. It is the sort of place you would expect to meet a fairy in the moonlight!! (I didn’t see one I’m afraid but I saw some rabbits).

It is very hot and I am sitting in my shirt sleeves in a tent and every time I write one line of this letter somebody comes and interrupts me! I went to a lovely big castle the other day – it was ever so old – the Romans built the old bit and the Normans built the new bit…. There is a big ditch around the castle, full of water, so that people couldn’t attack it without getting their clothes wet and so getting into trouble with their mummies.

I must go and have my lunch or I won’t get any and that would be a BAD THING (I wish I was having it with you).

Private correspondence reveals a wide range of voices – men and women, rich and poor, old and young. In some circles letter writing became an art form. Topics range from love to war with a host of daily details on the way. Raw feelings of grief or adoration are expressed to the long dead in words which we feel privileged to encounter today. Nor do letters stint on the difficulties which can arise in family relationships at any period of history. This writer is in full sympathy with her friend;

I think you have done all you could, and all you ought to do under your trying circumstances, and the having done so will I have no doubt be a cause for future comfort & consolation to you. I have no words to express my abhorrence of your Mother’s unfeeling conduct, but on the whole I fancy it is just as well that you two should not meet at present.

Letters at DHC frequently touch on serious issues, such marriage arrangements, and many document the financial negotiations which were progressing in tandem with the ‘romance’. Uncle George Cokayne perhaps expresses realistic hopes for a marriage when he writes;

My Dear Maurice

I am most glad to hear of your approaching marriage which is sure to be a happy one for unless indeed the Lady be very unreasonable she cannot fail to work comfortably in harness with you.

There are few more direct, accessible and affecting types of document than letters– they are a wonderfully effective way to access the stories held in archive collections. Volunteers at DHC have scoped over 400 items of correspondence from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and we are grateful for their work which has allowed us to generate this blog.

[…] “Life & Letters,” Correspondence, The Walt Whitman Archive; “Archival Types – Letters and Correspondence,” Dorset History Centre blog, Apr. 20, 2020; “Greetings from the Smithsonian Postcard […]