We have just come to the end of our series of blogs highlighting the wide variety documents contained in two collections of grangerised books held within our archive; Hutchins Extra illustrated and Royal Weymouth. We couldn’t finish this series without writing a little bit about the man responsible for putting these books together, A.M. Broadley.

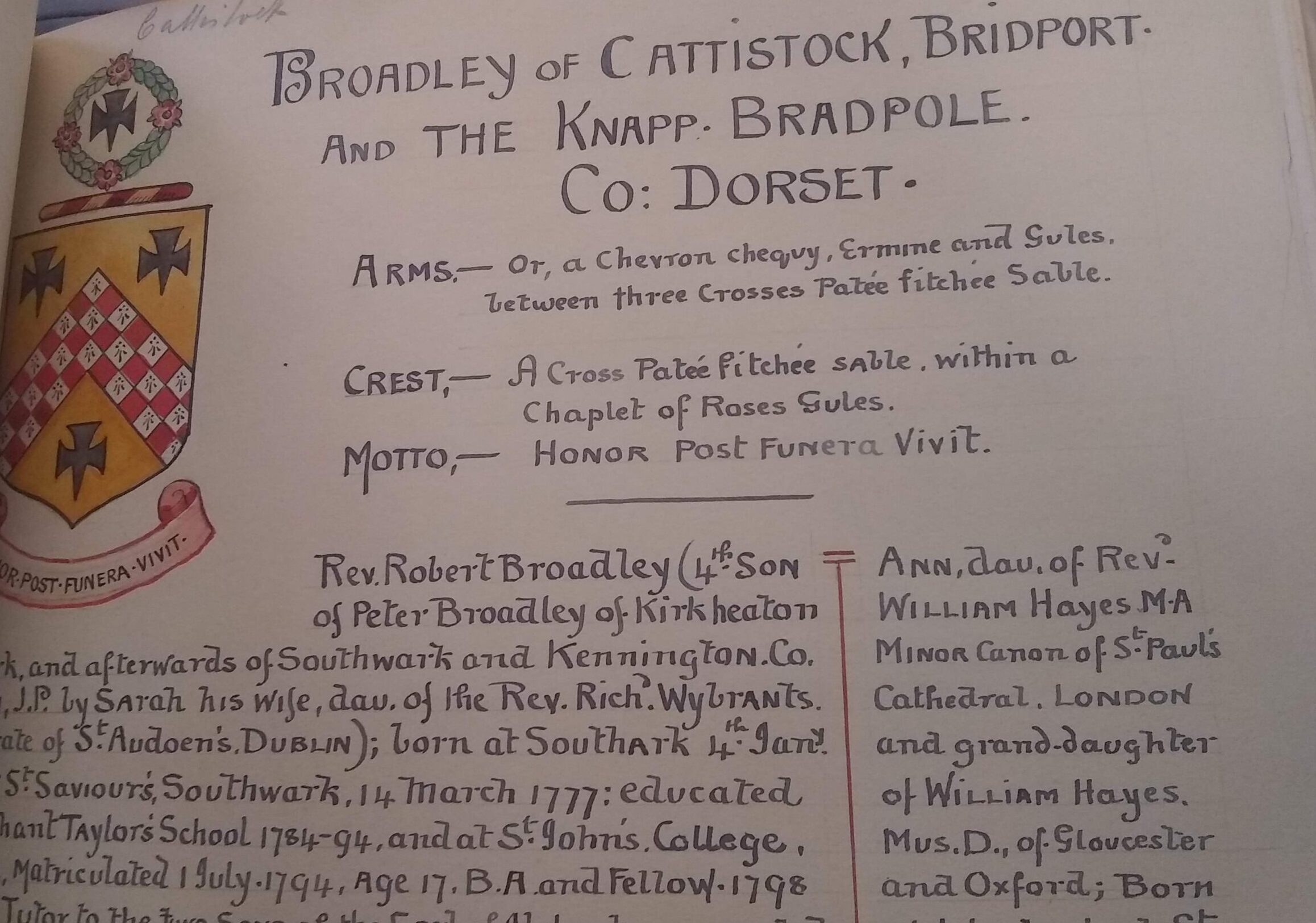

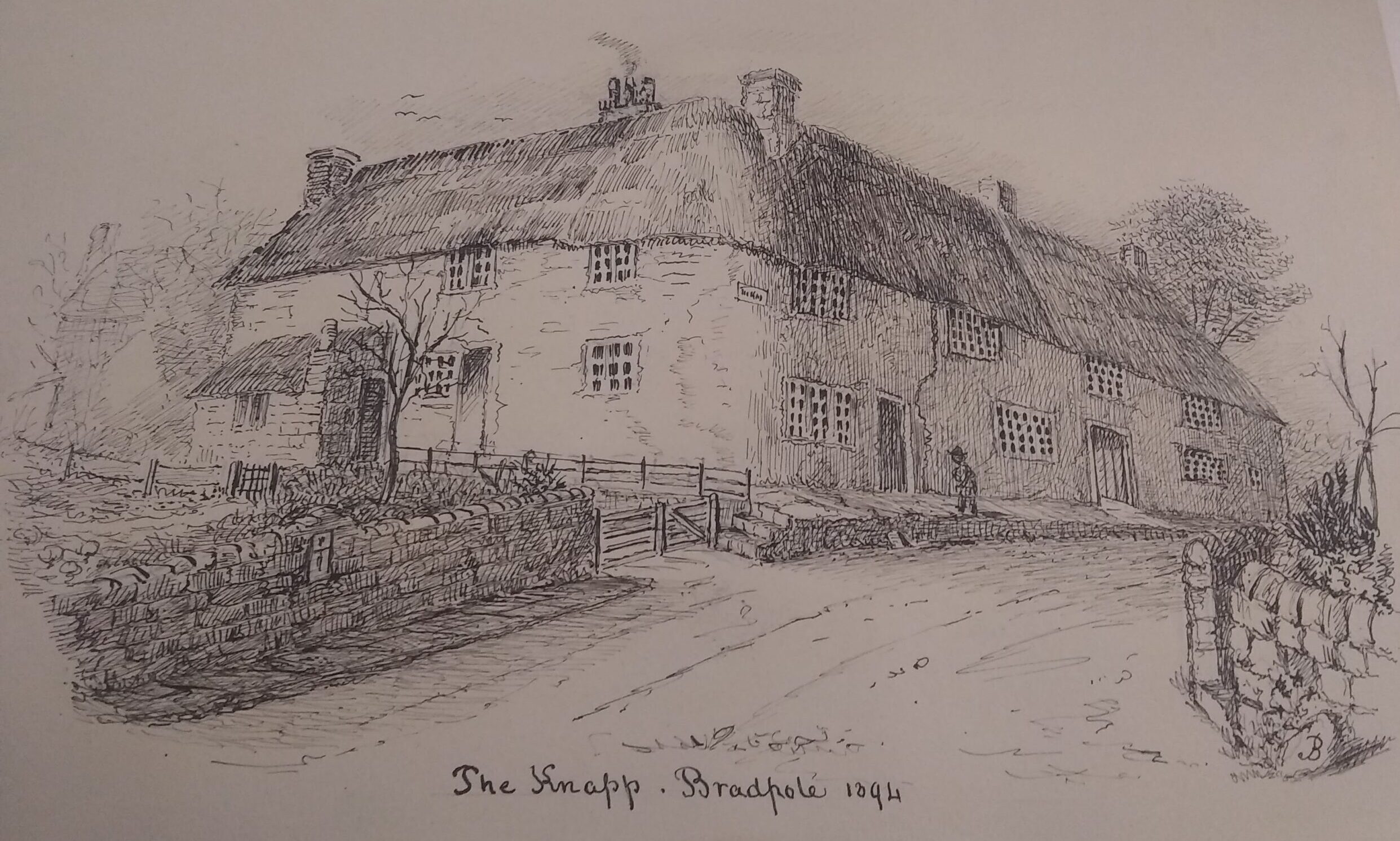

Alexander Meyrick Broadley was born on the 19th July 1847 in Bradpole, where his father was the vicar. From his birth in this Dorset village he went on to lead an extremely eventful life becoming embroiled in scandals, earning the enmity of the Prince of Wales and defending the leader of an Egyptian uprising.

Broadley qualified as a lawyer and joined the Indian Civil Service in 1869, becoming the assistant magistrate and collector of Patna, Bengal. As well as his work as a lawyer he also conducted a survey of the ruins of the Nalanda monasteries at Burgaon. His report on his findings was published in 1872, but shortly after this he had to leave India and the civil service after he was accused of what contemporary newspapers described as ‘charges of a serious nature’. Later accounts of his life suggest that the charges related to homosexual behaviour.

To escape the scandal Broadley moved to Tunis where he worked as a lawyer and correspondent for The Times and was very involved with the freemasons. He also continued with his historical studies, producing a well-received book ‘The last Punic War, Tunic past and present’ in 1882.

In 1882 he was appointed as one of the defence lawyers for Ahmed ‘Urabi, also known Orabi Pasha, who had led a rebellion in Egypt. Broadley forced a compromise which saw Ahmed ‘Urabi sent into exile in Columbia and from this point onwards he was nicknamed Broadley Pasha by English society and the press.

After the trial Broadley returned to England and worked his way into the highest echelons of society. He became the unofficial editor of the periodical ‘The World‘. At his birthday party of 1887, which was reported in the Bridport News, entertainment was provided by some of the best-known singers of the time and the guest list included royalty, ministers and nobility.

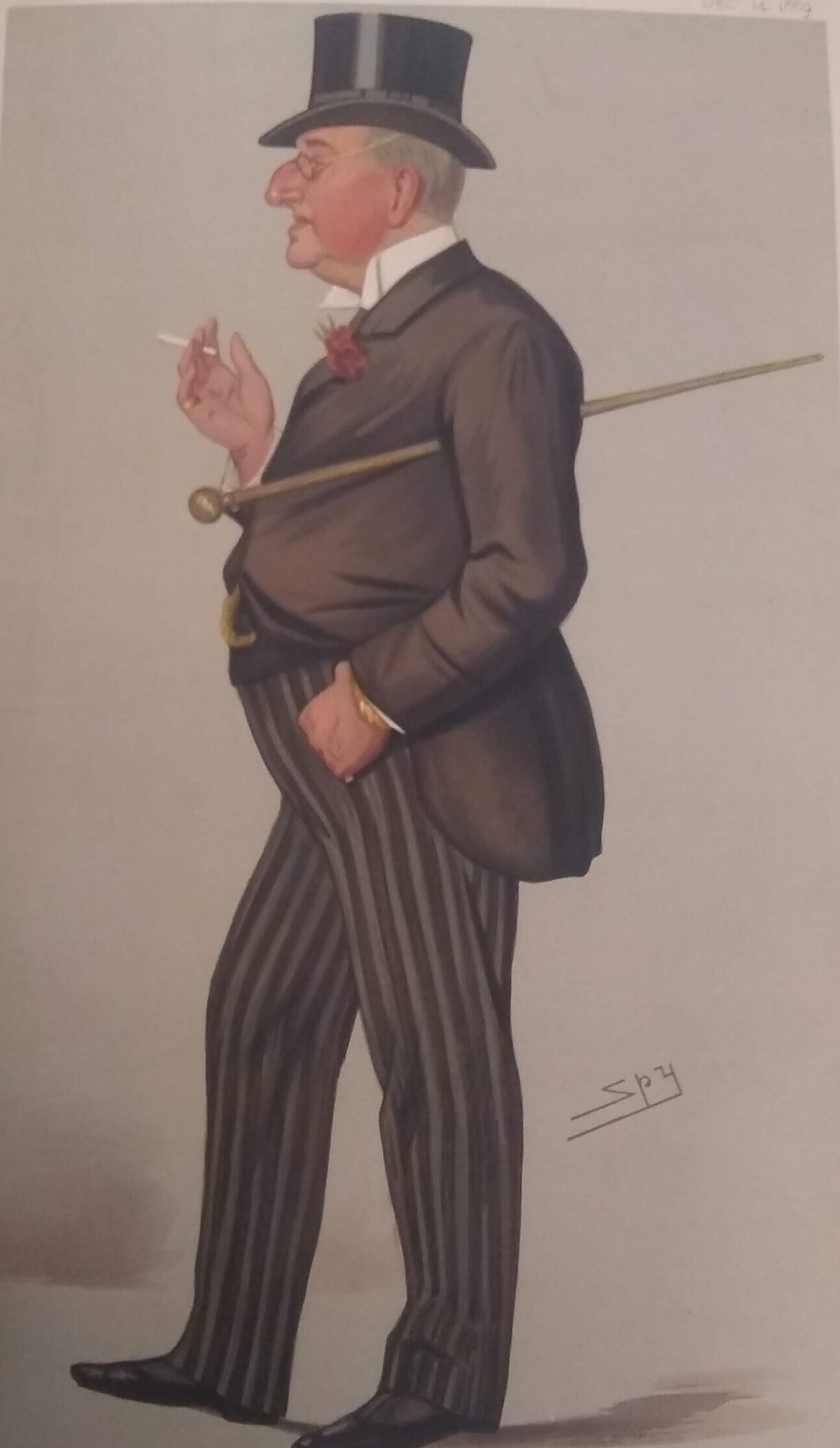

In 1889 Broadley’s picture appeared in Vanity Fair, which should have been a sign that he had become an accepted part of high society, but instead led to a second exile. The Prince of Wales, who later became King Edward VII, objected to Broadley’s inclusion in a magazine that had published pictures of his family. He forced the magazine to print an apology. Why the Prince of Wales disliked Broadley is not clear, some reports claim it is because he knew of his reputation in India, but it may have been because of his connection with the Cleveland Street scandal. Broadley was said to have been a patron at the male brothel that was raided in 1889. The government was accused of covering up the fact that many aristocrats were clients of the club. There was even rumours that the Prince of Wales son Prince Albert Victor was involved, but this has never been substantiated.

The apology printed in Vanity Fair led to society turning against Broadley and in January 1890 The World paper published a notice that Broadley had resigned and would have no further connection with the publication. Press reports reporting this announcement praise Broadley’s skill in writing gossip and describe his opulent lifestyle. The Dundee Chronicle of 4th of January 1890 writes:

Mr Broadley’s receptions were amongst the most stylish things in London. Mr Broadley himself was a very florid, verdant-green looking gentleman, in gold spectacles with an affectation of ennui and vacuity which suggested “form” and opened many doors for him in the West End.

The same report suggests that he had been making two to three thousand pounds a year through his work for The World, promotion and exploitation. There is also a suggestion in these reports that many of those who once courted him were celebrating his downfall.

Exiled for a second time Broadley ended up in Belgium, where he once again worked his way into the elite and even associated with the King. Bizarrely there are reports that he put his past behind him by denying that he was the same A.M. Broadley who had been thrown out of England!

In 1894 Broadley returned to England again. In 1896 he met Ernest Terah Hooley, a financial fraudster, and started promoting his investments. There were reports at the time that Broadley was the financial mastermind behind Hooley’s cons. This was never proved, but Broadley freely admitted assisting him.

In 1898 Hooley was made bankrupt. Broadley was charged with contempt of court after trying to bribe Hooley to change his testimony in order to protect his employer, the Earl of Warr. Hooley alleged that Broadley had intercepted money intended for others and made thousands acting as his promoter. Broadley denied this. Broadley was found guilty of insubordination and perjury and ordered to pay costs, which was considered a very light sentence.

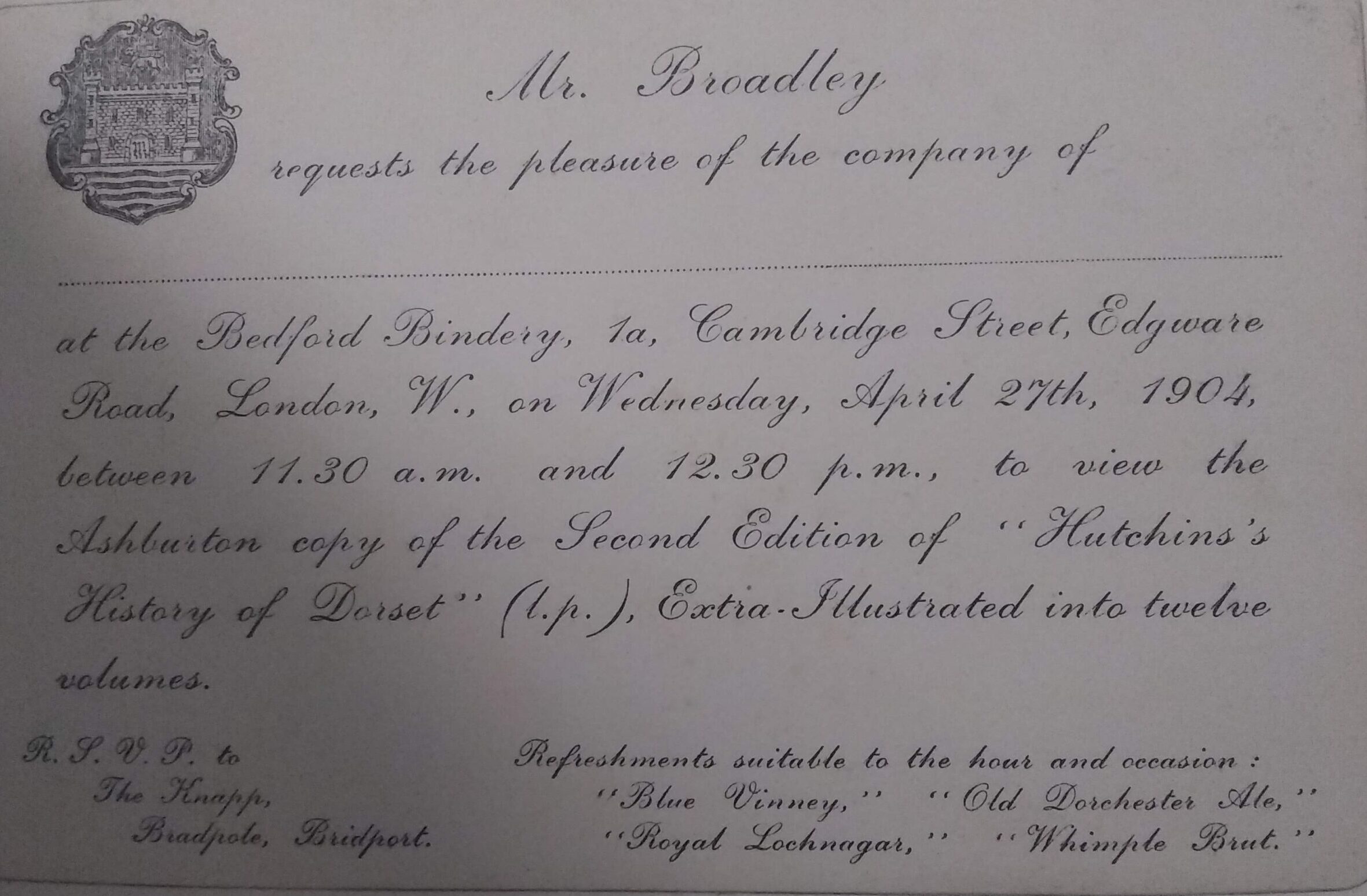

After the case Broadley retired to The Knapp, his large house in Bradpole, where he wrote and collected books. He died in 1916.

The story of Alexander Meyrick Broadley’s life paints a picture of a clever and charismatic man who was not afraid to use his intellect and powers of manipulation for his own benefit. He had great belief in his own opinions, something that comes across when looking the Hutchins Extra Illustrated in which a large number of the critical cuttings and pamphlets included were written by Broadley himself. He seemed to have a remarkable ability to escape from trouble relatively unscathed and by the end of his life was remembered as a scholar not a criminal.

Broadley may have been a divisive individual, but the huge collection of books and documents that he left behind is an amazing resource and we have enjoyed discovering the treasures in the volumes in our Archive. We hope you have too.

—

This blog follows our monthly series on the 12 extra-illustrated volumes of “Hutchins’ History and Antiquities of Dorset.” You can read the rest of the series through the links below:

Part one: An introduction to the history and antiquities of Dorset.

Part two: The Pitt family, a piano player, and a plague of caterpillars.

Part three: Coastline, Castles and Catastrophe

Part four: A Phenomenon, Fake News and a Philanthropist

Part five: Antiquities, Adventurers, and an Actress

Part six: A Gaol, a Guide and a Man of Great Girth

Part seven: Physicians, fires and false allegations

Part eight: Graves, Grangerising and a Man who wore Green

Part nine: Desertion, Drinks and a Diarist

Part ten: Music, medical miracles, and mills

Part eleven: Courtiers, Criminals, and Cuttings

Part twelve: An Abbey, the Arts, and the Athelhampton Ape

Rev. John Hutchins – author of a cursed book?

Royal Weymouth, Volume 1 – Cuttings and Correspondence

Royal Weymouth, Volume 2 – Devonshire and Dialect