Wills are basically a statement of how you wish your property to be disposed of following your death. The 1540 Statue of Wills laid down that a will should deal with real estate (i.e. land and buildings) and personal property (e.g. goods, money). The main change was that through a written Will a landowner could dictate who would inherit their land.

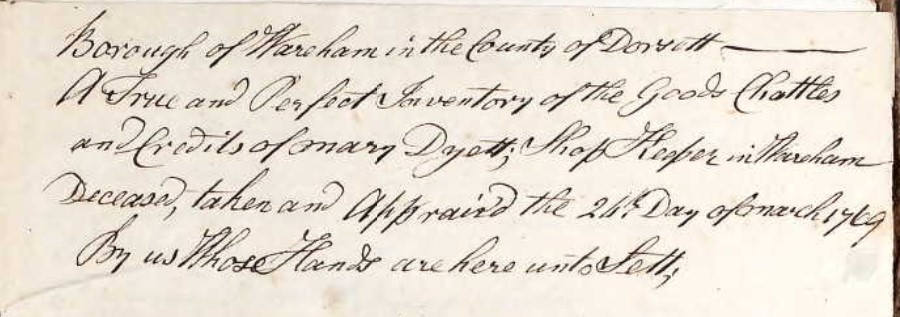

Anybody, with a few exceptions such as criminals, lunatics and ex-communicants, could make a Will. However, before the Married Women’s Property Act of 1882 women did not make Wills in their own rights as their property was deemed to be owned by their husband. Therefore, most of the Wills for women prior to this date were made by widows, spinsters or women who had their property rights protected in a marriage settlement. However, they may give further information too; the Will for Mary Dyett in 1769 states she is a widow her inventory also details her trade at the time:

The poor rarely made wills as their wishes were usually well known within the family, and their personal estate, such as it was, was usually divided up amongst the deceased family without the need of a written will.

—

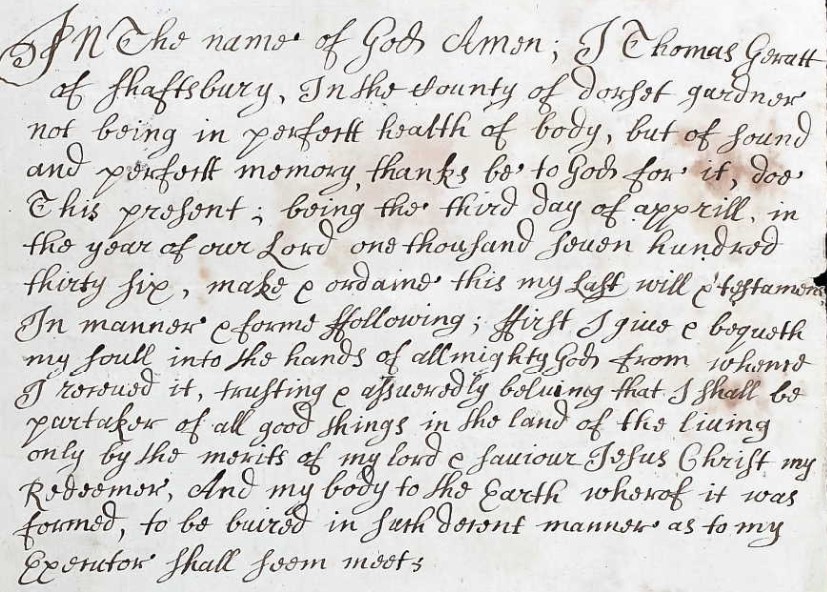

Wills usually start in a similar way as evidenced by the Will of Thomas Geratt of Shaston:

This opening statement gives the identity of the testator, where they are residing and sometimes their occupation. It also confirms that although not always in perfect health, they are capable of making a will being ‘of sound and perfect memory’. Will’s are dated, and whilst they could be made many years before a person died, it is more usual to find that they were made shortly before the person died.

Thomas Geratt’s will was made on 3rd April 1735 and the burial of a Thomas Garrot is recorded in the registers of Shaftesbury St. James on 10th April 1736. Therefore, when looking for a Will, you will need to remember that the date it is recorded will be the date it was proved, not made!

It may also state where the testator/testatrix wished to be buried, which may not have been in the parish they were residing in, or that, as in this case, the final decision was to be made by the Executor of the Will.

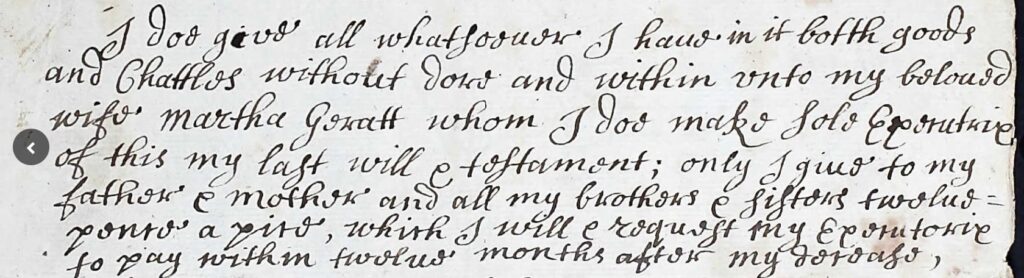

The names of beneficiaries, executors and witnesses can provide valuable information on family relationships. Thomas Geratt appointed his wife as executor but gave only vague details concerning his family members who were to inherit:

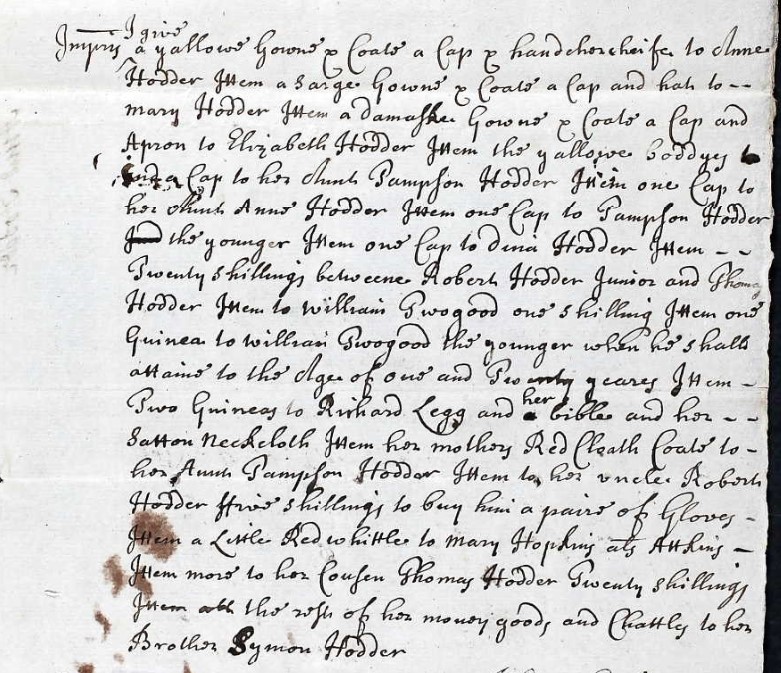

By contrast, the Will of Anne Hodder in 1719 gives an extensive list of family members:

If the Will was made some time before the person died any amendments or additions to the original Will are recorded at the end in what is known as a codicil.

—

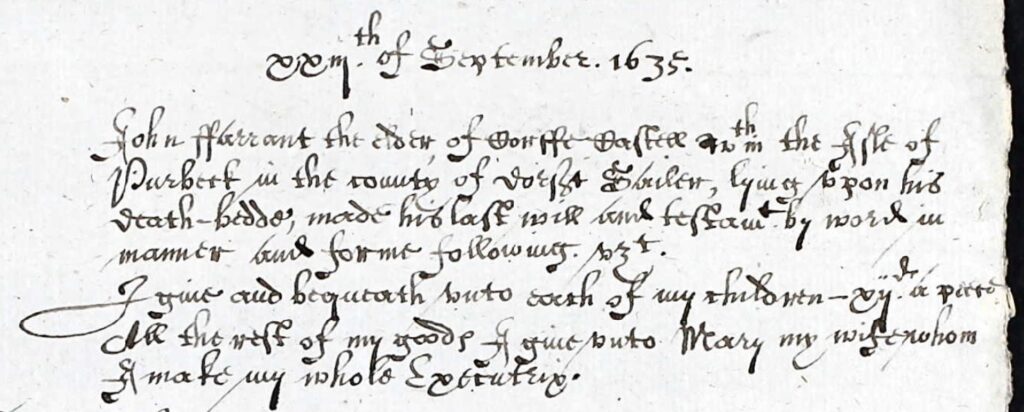

If the person was very ill and unable to write or have a will written by a lawyer, oral statements of intention could made. This was known as a nuncupative Will such as can be seen in the Will of John Farrant, in 1635:

From 1837 nuncupative wills were no longer permitted except for members of the armed forces.

—

After someone’s death the Will had to be proved by a probate court to ensure that the Will was genuine and ensure some supervision of the administration of the will by the executors. Before 11th January 1858 wills were proved by church courts. This was usually the Archdeaconry Court for the area of the diocese in which the person lived, for Dorset this was the Dorset Archdeaconry. If the individual held land and property in more than one Archdeaconry, but in the same diocese, the will would be proved by the Bishops Court called the Consistory Court. For Dorset this was the Bristol Consistory Court. Wills proved in the Dorset Archdeaconry and Bristol Consistory are held at the Dorset History Centre.

However, there are some exceptions to this rule. The ‘Peculiar Courts’ were areas outside the authority of the Archdeaconry, which had the power to grant probate. These were usually made up from a small number of (or even just one) parishes and were usually a hangover from the pre-Reformation period when the local monastery had held a court. A number of these Peculiar Courts exist for Dorset including, but not exclusive to, Corfe Castle, Burton Bradstock, Milton Abbas, and Wimborne Minster.

If land and property were held in more than one diocese the will would be proved at the Prerogative Court of Canterbury (which was actually based in London) and had a reputation of being more competent and professional than any other probate court. As a result, many ordinary people chose to have wills proved at the Prerogative Court of Canterbury rather than a local court. These Wills are held at The National Archives.

—

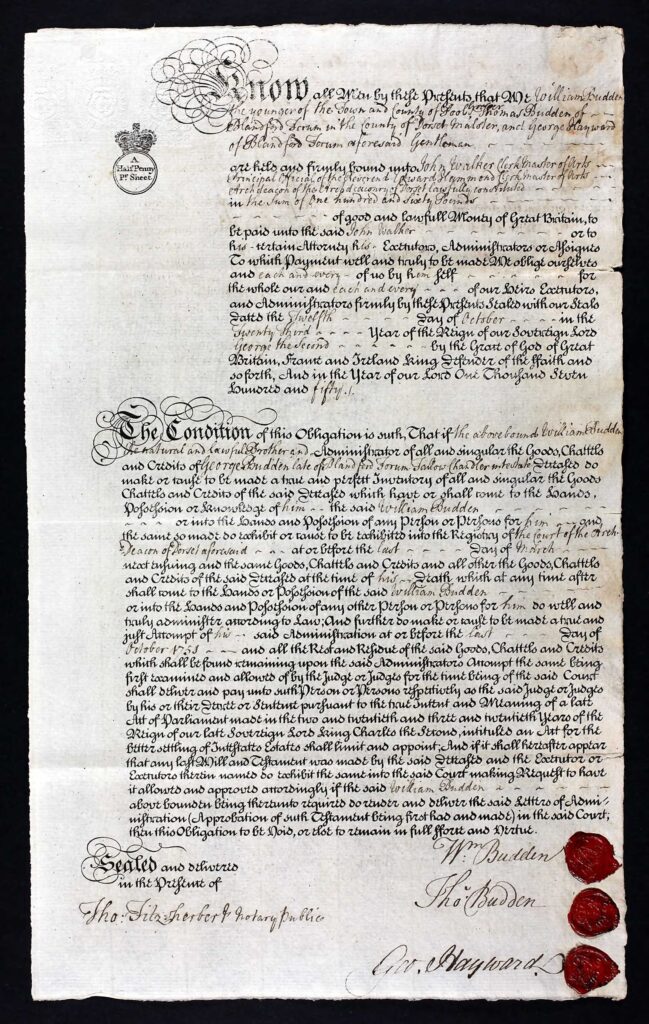

If someone died without making a will (intestate) it may have been necessary to obtain legal right to administer the estate. This document is known as a Letter of Administration (or Admon) and appoints an executor.

The 1670 Statute of Distributions dictated how a person’s estate should be divided if no will was made: the widow received one third, the remainder was divided equally between the children or other relatives who stood as next-of-kin. A woman’s estate went entirely to her husband if she had one. If no relatives could be found the estate would in theory, after the payment of any creditors, pass to the Crown.

A standard pro forma was used for Letters of Administration, with the relevant bits completed, although sometimes it was written fully by hand. Letters of Administration provide limited information; the names and possibly addresses of the deceased, the next of kin and the person appointed as executor and a date. Occasionally the deceased occupation was also listed, as can be seen in the case of George Buddens Admon:

—

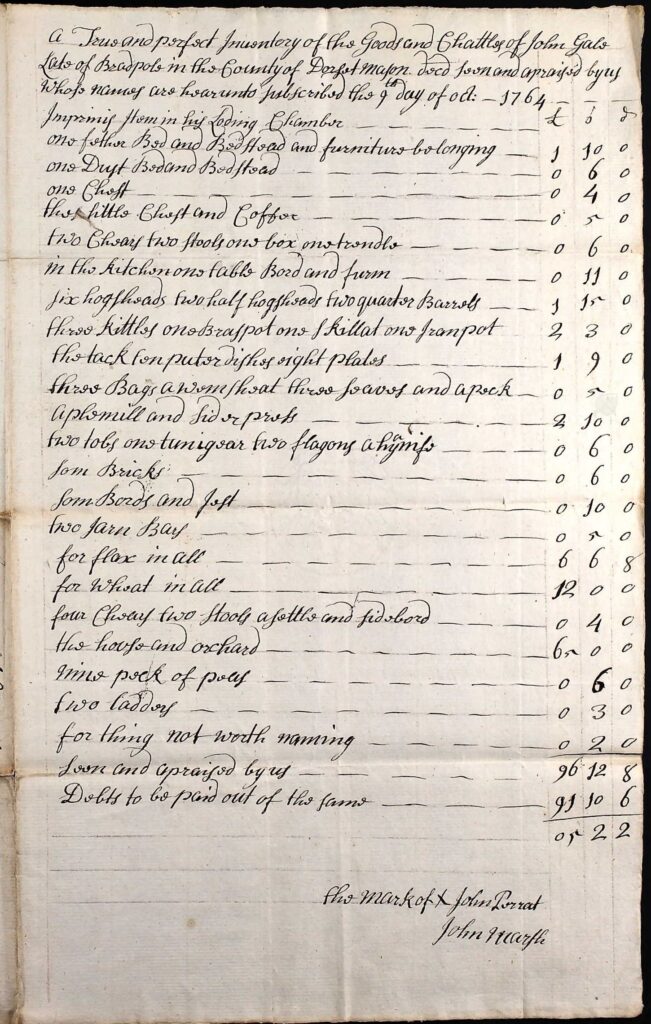

Wills and Letters of Administrations can also contain an inventory of all the ‘goods and chattels’ of the deceased. This lists and values the personal property of the deceased, including items such as clothing, furniture, household goods and even animals, and can provide an insight into the lifestyle and wealth of the individual. Such an example is John Gale’s inventory below:

Details of Wills, Admons and Inventories created by Dorset Archdeaconry, Bristol Constituency and the Peculiar Courts for Dorset can be found on a card index of wills, arranged alphabetically by surname, at the Dorset History Centre (although work is in progress to get this index onto our online catalogue). The wills themselves are on available to view on microfilm, or can now be accessed through the Ancestry website.

However, as a copy of the probate Will was given to the executor it is always worth searching our online catalogue as well to see if there is a copy held in another collection for your ancestor. Probate Records for England and Wales, dating from 1858 up to as late as the last six months, are available to search, and order copies of, on the Government website.