For this blog local Dorset author Minette Walters tells us about the inspiration behind her upcoming book…

—

For anyone who relishes tales of courage and heroism against overwhelming odds, I recommend a study of the siege of Lyme Regis during the English Civil War. I researched it for my new novel, The Swift and The Harrier, due out in November, which depicts the lives of two Dorset families from the start of the war in 1642 to the King’s execution in 1649.

The siege of Lyme forms the backdrop to the middle chapters of my novel, and I can’t remember enjoying the researching and writing of a subject so much. Even the driest accounts of the beleaguered town’s dogged two-month resistance – and ultimate victory – against the King’s western army make exciting reading; though to truly understand the magnitude of what Lyme faced I would advise a visit to the Cobb and an hour’s contemplation of the high ground that surrounds the town.

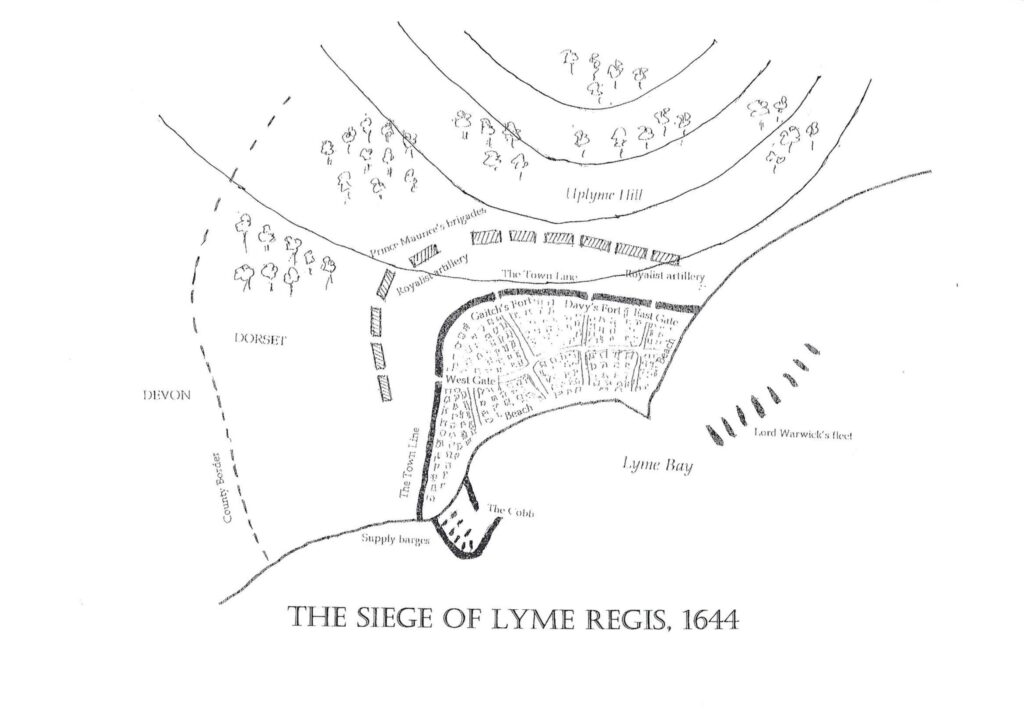

The King’s western army, commanded by his nephew Prince Maurice, numbered six thousand and mustered on Uplyme Hill on April 20th, 1644. By contrast, Lyme’s garrison was a mere one thousand, and their only protection from frontal assault was a mile-long earth bank behind a deep trench, known as the Town Line, that stretched from the western end of the Cobb to the shoreline in the east. Prince Maurice held the hill with batteries of light and heavy artillery, and, by any reckoning, should have over-run and occupied Lyme within days. Yet in eight weeks, and despite constant bombardment of the town by cannons, fire-darts and musket shot, he was never able to penetrate beyond the Town Line.

Why not? One answer lies in the compelling leadership of Colonel Robert Blake, the commander of the garrison. His name should be as well-known to us as Thomas Fairfax or Oliver Cromwell because his triumph at Lyme was bettered only by his subsequent holding of Taunton for Parliament through three sieges and against even greater odds. After the war he was appointed Admiral of the Navy and, such were his successes that he’s credited with establishing England’s naval supremacy – a dominance of sea-power that was maintained for another two and a half centuries. It remains a mystery to me that so able a man has been largely forgotten.

Nevertheless, Blake is better remembered than the true heroes of Lyme, who were referenced in the refrain of a popular song that became fashionable in London as news of the town’s resistance spread.

‘By all tis known, the weaker vessels are the stronger grown.’

The allusion was to the women of Lyme, whose indomitable courage was applauded throughout Parliamentary England. Not only did they dress as men to stand with their fathers, husbands and brothers on the earth bank to make the garrison seem larger than it was, they fought the fires caused by the relentless Royalist bombardment, hauled powder kegs to where they were needed, re-loaded muskets, tended the sick and buried the dead.

The war made them the equals of men, but it was another three hundred and fifty years before another conflict – World War 1 – persuaded Parliament to finally grant women the beginnings of legal equality through the Representation of the People Act of 1918. History doesn’t relate whether the men of Lyme afforded their ladies the same respect after the siege as they’d shown them while it endured, but, if not, perhaps we can right that wrong nearly four centuries later.

March is Women’s History Month, so allow me to offer you the wonderful women of Lyme and ask you to raise a glass to their memory!

—

This was a guest blog written as part of Women’s History Month. Should you be interested in writing a piece about Dorset history, please get in touch with us: archives@dorsetcouncil.gov.uk