In 1799 two significant things were born. Both would make significant contributions to science and research. The first, The Royal Institution of Great Britain was established in March 1799, and is still in existence, having seen no less than 15 Nobel Laureates pass through their doors, and 10 chemical elements be discovered by its members throughout its history.

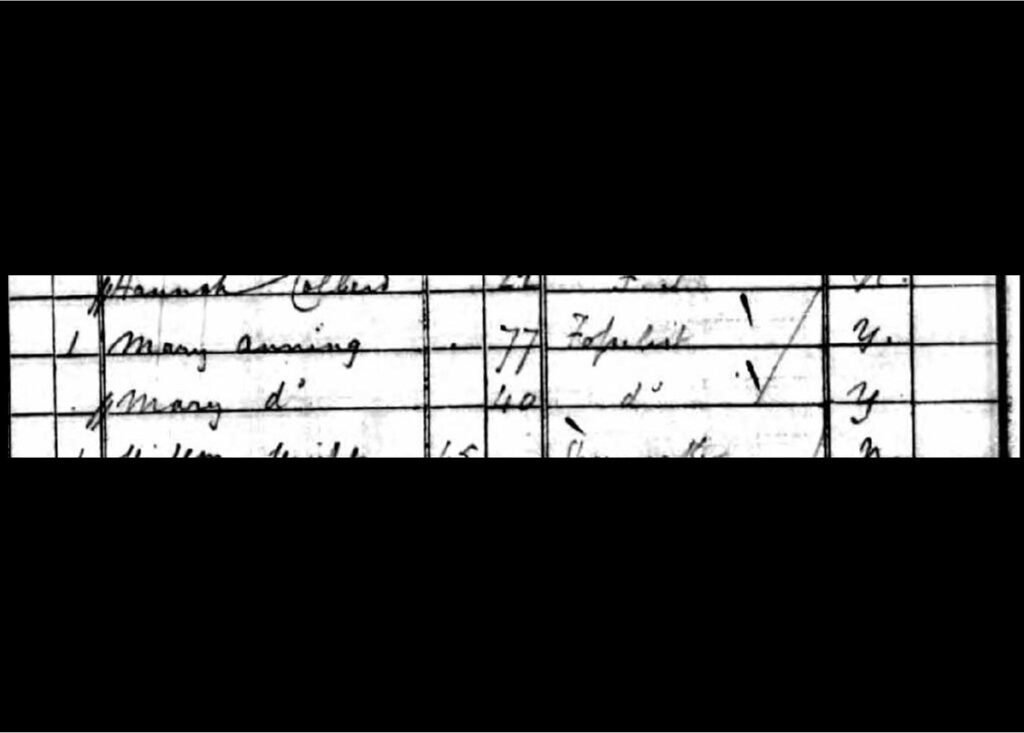

Two months later, Mary Anning was born in Lyme Regis to Richard and Mary Anning (known as Molly). Two-hundred and twenty years later, she about to be thrust back into the public limelight with the release of the Kate Winslet-starring film ‘Ammonite’.

Richard was a cabinet-maker who sold fossils to tourists to make some extra money. Mary was named after her older sister, who had died months before she was born after an accident with an open fire. Eventually, Mary would be one of ten children born to Richard and Molly, however only two of the children survived to adulthood, painting an ongoing tale of heart-break for the family.

Mary learned to read and write through the Congregationalist Sunday School. Congregationalists emphasised the importance of education for the poorer members of society, and undoubtedly Mary benefitted from this as she grew up.

The French Revolution had made continental Europe a less desirable holiday destination, and had forced wealthy aristocrats to embrace the ‘staycation’, as they holidayed in coastal towns around England. Lyme Regis undoubtedly benefitted from this boom, and the Anning family would make the most of this. Fossils, found aplenty around the town, had long been thought to have medicinal or mystical properties, and the Anning family made the most of this fascination, by selling fossils to the tourists. Richard would often take young Mary, and her brother Joseph, to the cliffs around Lyme Regis to gather fossils for sale outside their home.

In 1810, Richard, having suffered from tuberculosis and injuries caused by a fall from the cliffs, died aged 44, leaving the family with no savings and debts. Fossil selling continued for young Mary (aged 11 at the time of her father’s death) and Joseph to help make ends meet. It was less than a year later that Joseph, and then Mary would make their first ‘big’ discovery. Joseph dug up the not-inconsiderable 4 foot skull of a dinosaur. Months later, Mary would discover the remainder of the skeleton.

The family were paid £23 for the skeleton (which would be worth roughly £1100 in modern money). The skeleton made its way to London and the British Museum, and fascinated society. Biblical attitudes to the history of the Earth were still commonplace. The Ichthyosaurus (as it had been named) skeleton challenged these attitudes.

The nature of this work meant that income was unreliable. In 1820 Mary and Joseph had made no major discoveries, and the family struggled to make ends meet. With the threat of having to sell furniture to cover their costs, the Anning’s were aided by an interested patron. Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas James Birch of Lincolnshire, who had bought many samples from the Anning’s over the years held a large auction of these to help the family survive. More importantly, the auction, which attracted buyers from continental Europe, helped to build the name of Anning within the geology world.

Mary continued to search the cliffs throughout the 1820s and 1830s, becoming more and more knowledgeable about her finds. She would transcribe academic articles and add her own notes to these pieces to illustrate them. Anning taught herself geology, anatomy, and how to illustrate accurately. She famously discovered a Plesiosaurus in 1823, a Pterosaur in 1828, and numerous other key findings in between. Mary had an appetite for learning about these discoveries and was clearly comfortable conversing about her discoveries with all comers, often knowing much more than her male counterparts who would go on to author papers on Anning’s discoveries. A combination of her gender and her social position meant she was often overlooked as collectors took credit for her work. This naturally upset Anning.

In addition, by the 1830s financial difficulties had once more arisen for Mary. Long spells between discoveries, coupled with general economic difficulties in Britain caused problems for Mary. A £200 sale in December 1830 helped, but by the middle of the decade, Mary was struggling once more, losing around £300 in savings. During this period Mary left the Congregationalist Church, for various reasons, and became an Anglican, remaining deeply religious.

Anning’s work dropped off in the 1840s, as she began to suffer the effects of having breast cancer. The Geological Society, who had been supportive of Anning, helped raise money to support her in her ill-health, and the newly created Dorset County Museum made her an honorary member.

Mary Anning died on 9th March 1847. She was 47. She was buried in the churchyard of St Michael’s, Lyme Regis, and a new stained-glass window in her memory was installed in the church in 1850.

—

For the best information about the life and legacy of Mary Anning, we recommend you get in touch with Lyme Regis Museum who hold various samples and materials relating to her work.

Dorset History Centre hold some records and various books relating to Mary Anning:

- D-PAV/33 – A Short Account of those who have done Geological work in the Neighbourhood of Charmouth, by W.D.Lang, FRS: Mary Anning…

- D1/NS/1 – Letter: Mary Anning of Lyme Regis, to Miss M Lister of 8 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London, 1840.

- RON/5/2/3 – Photo of Pterosaur found by Mary Anning, 20th century

- RON/5/2/4 – Fossil Hunting in Dorset: In the steps of Mary Anning. Extracted from “Coming Events in Britain”, Sep 1965

- D-LRM/T/18 – Inquest and testimony into the death of Elizabeth Hoskins who was struck by lightning whilst caring for a young child [Mary Anning] 20 Aug 1800.

- PE-LR/CW/12/1 – Correspondence concerning the restoration of Mary Anning’s tomb stone including letters from Annette Anning [great grand niece]; suggestions for restoring the inscription; and some genealogical notes on the Anning family. 1925

- PE-LR/CW/3/28 – Proclamation for a faculty authorising the removal of certain tomb stones to another part of the church yard but leaving the stones of Mary Anning and the Revd F Hodges. 1955

- PE-LR/CW/9/1 – Letter from the Geological Society of London to the churchwarden offering help with the renovation of the Mary Anning memorial window which includes a transcript of the inscription on the window and a postcard picture of Mary Anning. 1975

- Mary Anning, 1799-1847, by Richard Curle, library reference 567.9

- Mary Anning of Lyme Regis, by Christopher Tickell, library reference 567.9

- Under Black Ven: Mary Anning’s Story, by Judith Stinton, library reference 567.9

- Curious Bones : Mary Anning And The Birth Of Paleontology, by Thomas W. Goodhue, library reference 567.9

- We hold various other books too. Please have a look at our library catalogue for more details.