On 1 November 1943, a man, claiming to be refugee, arrived in Poole by flying boat and told a story of how he had escaped from a German internment camp in Occupied France.

Little did he know then how short his stay in Britain would be.

This was wartime Britain and ports and airports like Poole were watchful for anything suspicious. Thanks to a sharp-eyed MI5 port security officer at Poole terminal, within five months that flying boat passenger was hanged as a spy in Pentonville jail.

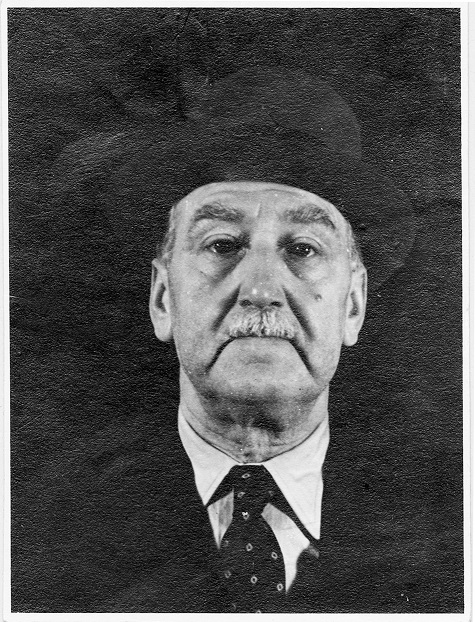

Much of the story of the traitor, Oswald John Job, was been unearthed in The National Archives, in the ‘KV’ files released by the Security Service. Ed Perkins, author of Britain’s Forgotten Traitor, argues that there may have been a miscarriage of justice.

Interned

Job, known as John, was born in London (the son of German immigrants) and grew up in the East End; married and served time abroad for his part in a gem raid.

Then he abandoned his wife and young daughter.

Job went to Paris where, bigamously, he married a French woman and ran two businesses, one making artificial eyes. All was going well until war broke out and soon Nazi boots were marching down the Paris boulevards. With much of France under German Occupation, Job was interned and thrown into prisons, ending up at the St Denis internment camp.

Nearly three years later, Job, who despised life behind the wire, said he was close to breakdown. Desperate, he struck a deal with the Nazis. They would free him if he agreed to return to Britain and spy for them.

Arrival at Poole

Within weeks, after being taught spycraft, he arrived at Poole flying boat terminal, waiting to be interrogated in the requisitioned Poole Pottery building.

It was 1 November 1943 and, in confident mood, he approached an officer. Job told him he was a special passenger because he had escaped. He was given a curt reply.

‘Wait your turn.’

Little did he know that that security officer, Lt Desmond Burke, would later seal his fate. He was a port security officer, answerable to MI5, who had their Poole HQ at 18 High Street in what is now a Thai restaurant with solicitors’ offices above.

When Job’s turn arrived, three men sat waiting to interrogate him. There was Lt Burke plus an Intelligence Corps sergeant and a local immigration officer, Arthur Clarke.

Job recounted the story of how he had escaped from internment and made it over the border to Spain, then Portugal.

Suspicion

The Poole men, now joined by their chief, Major Edward Humphries, smelt a rat.

Job was taken away to be searched by Humphries and the sergeant. He had a ready answer to everything and even pulled out his trouser waistband to show how much weight he had lost.

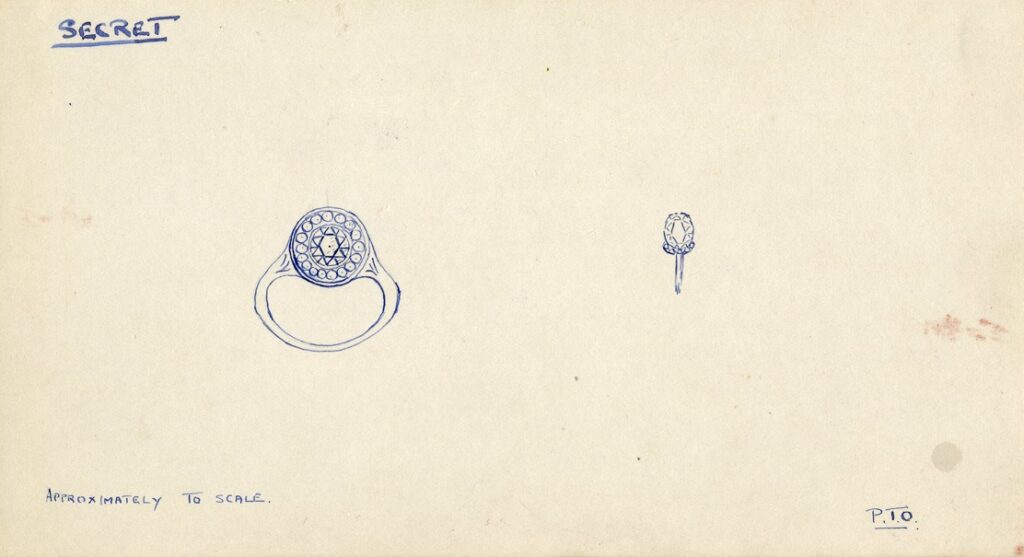

Pinned on his waistcoat was a gold tiepin and in a pocket they found a wrapped-up, valuable diamond ring. It was one, he claimed, he had given to his wife.

‘I could never sell my dear wife’s ring,’ he vowed.

Leaving him to dress, the searchers returned to the interrogation room. Humphries told Burke about Job’s impressive jewellery. Burke suddenly reacted. The jewellery matched the description MI5 had circulated weeks before in a ‘Most Secret’ message.

A British double agent had received a message from his German masters to say a courier would be bringing such jewellery into the country as payment for him. What the British did not know was who, where or when?

The Poole security men had identified him. They followed instructions. They let Job leave… but they tracked him.

Tailed

John Job stayed his first night back in England at the Merville Hotel in Bournemouth, by the Winter Gardens. It was the evening of a German air raid.

Next day Poole’s port security officers alerted their MI5 headquarters to say he was a train to Waterloo. When he arrived, MI5 watchers were waiting to tail him again. Meanwhile, counter-intelligence ordered Humphries, at Poole, to draw for them a sketch of the tiepin and ring.

Three weeks later, Job was arrested. He denied everything at first. But after being whisked off to a specialist prison interrogation centre, he cracked.

Confession

He admitted he had been recruited for a mission by the Nazis. He was to bring in the ring and tiepin and deliver it to a certain address.

And he was to report on bomb damage and morale in London.

- He showed told his interrogators where they could find invisible ink in his hollow razor and keys.

- He explained a code he had been taught for listening to wireless instructions.

- He had a list of addresses to where he was to send letters using the secret ink.

Job always claimed he took up the mission purely to get back to Britain and never intended to spy.

An Old Bailey jury did not believe him and he was hanged by Albert Pierrepoint in March 1944.

Guilty or Not?

This author, however, believes that Job, a habitual liar, may have been telling the truth. The Germans had given him little or no money and he was a onetime gem thief who had valuable jewellery burning a hole in his pocket. Instead, it is suggested that Job probably meant to ignore his mission, say nothing and hang on to the ring and tiepin for his own profit.

That was never suggested at his trial, but evidence to support the view includes a report compiled by the commandant when he was in hush-hush spy prison.

It states:

‘My personal opinion is that he is a shabby crook.’

And adds:

‘What he intended to do was to sell the jewellery for his own profit and lie low.’

In his diary, Guy Liddell, head of MI5 counter-intelligence at the time, said he, too, believed Job wanted to keep the jewellery. The files at The National Archives include a letter of thanks to the Poole team from Liddell. And another from the head of MI5, Sir David Petrie, who wrote to Major Humphries at Poole saying:

‘Your staff have done a good job and I feel I must not let this episode pass without sending you some letter of my appreciation and congratulation.’

It said that Job had now been ‘dealt with’.

He was… but was he hanged for telling lies?

—

This was a guest blog written by Ed Perkins, a Dorset writer, who honed his research skills as a volunteer at Dorset History Centre and at Poole History Centre. Britain’s Forgotten Traitor by Ed Perkins, is published by Amberley Publishing and will be published in April.

If he intended to doublecross the Nazis and keep the jewelry, why did he not say so? In any case he would have been offered the chance to become a double agent, as most captured Nazi spies were.Most of them agreed. Did he refuse and that is why he was seen to be an ideologically committed Nazi?

Several habitual liars and fantacists were recruited as double agents, so the fact that he was clearly both would not have disqualified him.

Richard, thanks so much for commenting on the blog. Feedback is always much appreciated.

First of all, let me stress that none of know what was inside Job’s head – though that was what the Old Bailey jury members were asked to try to do. There was certainly more than enough evidence to safely convict him and even more emerged after he died. As you know, I tend to think he took up the mission intending to carry it out but changed his mind after he got to Lisbon. He was away from his Nazi masters in Paris and increasingly aware that by summer 1943 the tide of the war was turning fast (North Africa, Sicily, Italy, the Eastern Front etc.) But to try to answer your specific points:

a) If he intended to double cross the Nazis and keep the jewellery, why did he not say so? In fact, he did. The Commandant of Camp 020, the prison for spies, wrote in his report, ‘My personal opinion is that he was a shabby crook. On his own admission, he intended to sell the jewellery in the event of financial necessity. He did not intend to work for the Germans because he was afraid. He did not intend to divulge his knowledge to the British because he was afraid. What he intended to do was to sell the jewellery and lie low’. Guy Liddell, the head of MI5 counter-intelligence, also wrote in his diary: ‘ My own belief is that he intends to pocket the jewellery and say nothing.’ Also, Job’s original confession states: ‘I proposed to keep the ring and tiepin.’ What is baffling is why this wasn’t flagged up in his defence when, absurdly, he claimed he intended posting them, anonymously, at some future date to the police. I can only put it down to poor legal advice. His defence team had very little time to prepare a case before the trial.

b) Was he offered the chance to become a double agent? No. The Liddell diaries reveal that this was considered but after a few days rejected. Why? Probably because i) Job wasn’t trustworthy. ii) MI5 and co had to pretend to behave as if they had not turned any German agents and this required a few unlucky ones to be executed to convince Berlin that nothing was amiss, iii) It was stated that, because Job’s means of communication with the Germans was to be through invisible ink on letters and not by wireless, the Post Office would find it too hard to monitor it. In his confession, Job offered to spy for the British. MI5 was not interested.

Job was convicted of being part of a jewel gang as a young man; arrived in London carrying a sum of money that Camp 020 said ‘wasn’t worth a tinker’s benediction’; and no immediate prospect of any further payment from the Germans. What he had got was the equivalent of £10,000 worth of jewellery at today’s value burning a hole in his pocket. But it would be easy to argue a very powerful case the other way. Saying he never intended to spy was certainly a classic ruse used by other spies arriving in Britain after they were captured. His internment camp file, unearthed after his execution, showed he had earlier in the war volunteered, eagerly, to spy for the Germans and that he purported to be very pro-Hitler (though the Nazis stated that they could find no previous political activity in his past.)

I think he was an unscrupulous chancer who would do only what was best for himself. In Britain, having been given little money by the Germans, my take is that he would have hung on to the ring and tiepin, then flogged it. But your guess is as good as mine.

In your report you state Job arrived in Poole on 1st November 1943.

He was hanged by Pierrepoint in March 1943.

Pierrepoint was a clever man……………..

Ah! A deliberate mistake! This should, of course, read March 1944. We’ve updated the main article now – thank-you for noticing the mistake.

What a fascinating and well-researched account of Oswald John Job’s story! The layers of intrigue and the meticulous work by MI5 and Poole’s port security highlight a tense and complex period of wartime Britain. Perkins’ insights into Job’s possible true motives add a compelling twist to the narrative. It’s intriguing to consider that Job might have been more of a petty thief than a dedicated spy. This post does a great job of shedding light on a lesser-known piece of history and the role Poole played in wartime espionage. Looking forward to reading more in “Britain’s Forgotten Traitor”!

That’s a really cool story about the spy capture in Poole! I’ve never heard of that before. It’s crazy to think that a flying boat could land in the harbour like that. I wonder if the spy was really guilty or if it was all a misunderstanding.