Since the formation of books as we know them, endpapers or endleaves have existed in some form, situated between the textblock and the binding. Not unlike endbands which were discussed in a previous blog, endpapers have evolved through time from providing protection for the textblock and structural support to becoming integral decorative features.

Endpapers in their basic form are additional leaves of paper, or originally parchment, that were added to either end of a textblock. The outer pages of a textblock are always more susceptible to damage so these leaves protect the written text.

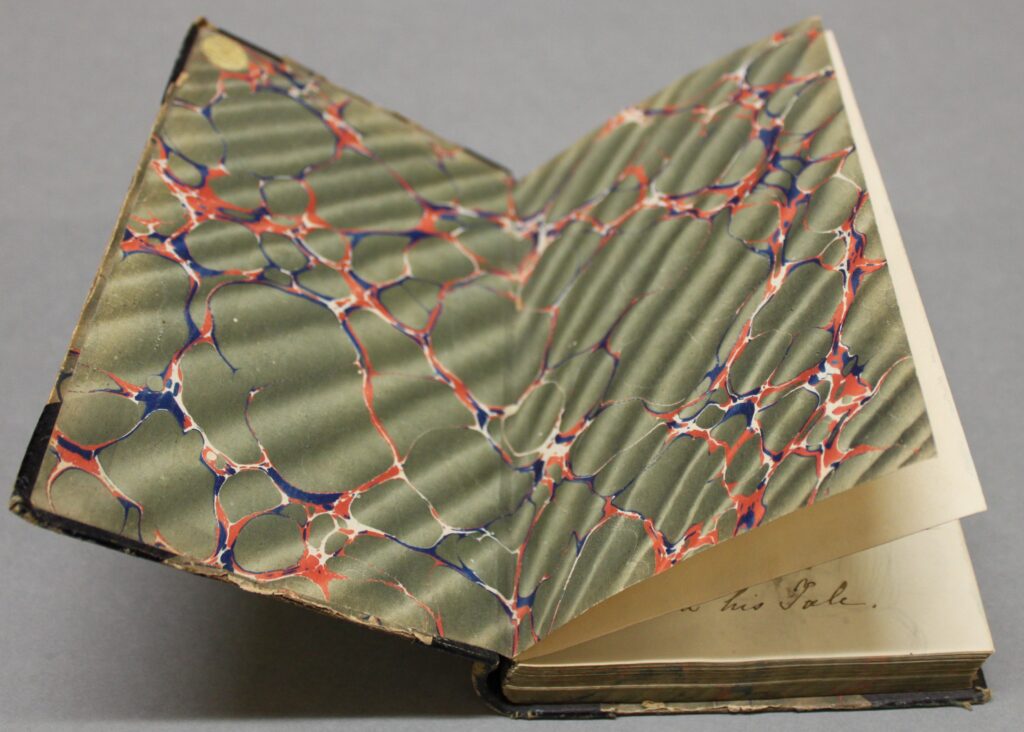

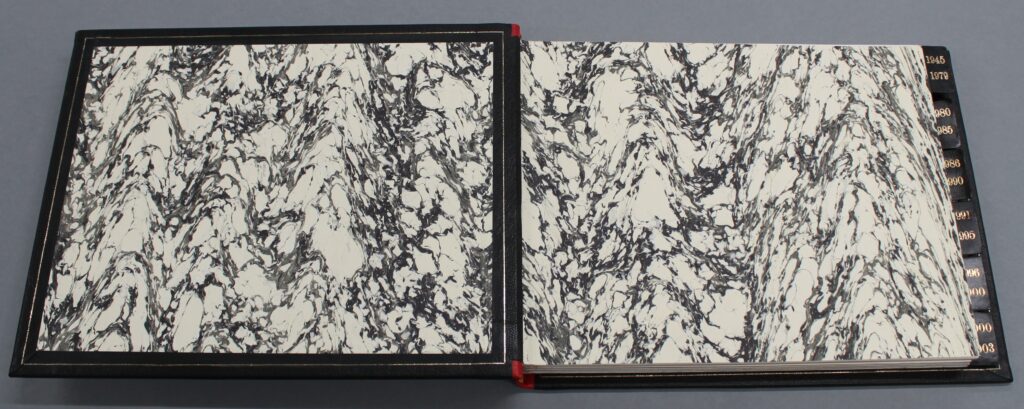

In the 15th century blank vellum sheets would have been used, before plain paper or waste vellum was utilised, and later manuscript and printed waste paper. The second quarter of the 17th century saw the introduction of marble paper which became increasingly popular. In the later 18th century silk and leather doublures became fashionable for upmarket bindings; an example is shown later in the blog.

The earliest marble used in England, from 1630s, was typically a pattern called comb marble. From the 18th century curl or snail designs and spot patterns emerged. Other decorative paper was also used, such as paste paper and brocade or Dutch gilt paper. From the 19th century endpapers were also used to display artistic work relating to the text or additional information such as maps.

Endpapers consist of the ‘pastedown’, the leaf that is adhered to the inside of the board, and ‘flyleaves’, which are the leaves that come between the pastedown and the textblock. As with endbands, the construction of endpapers become more complicated depending on the size, structure and the value placed upon the binding. Three main constructions are discussed below, but as with all hand-crafted items, bookbinders often use a variety of methods to make endpapers and studying bindings will show a wealth of techniques.

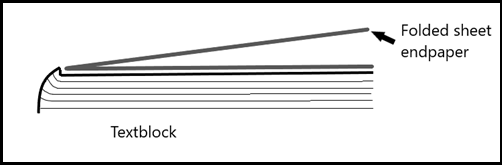

—

The simplest endpapers are constructed of a single folded sheet. It has little strength or structural integrity but provides protection to the first and last pages of the textblock.

—

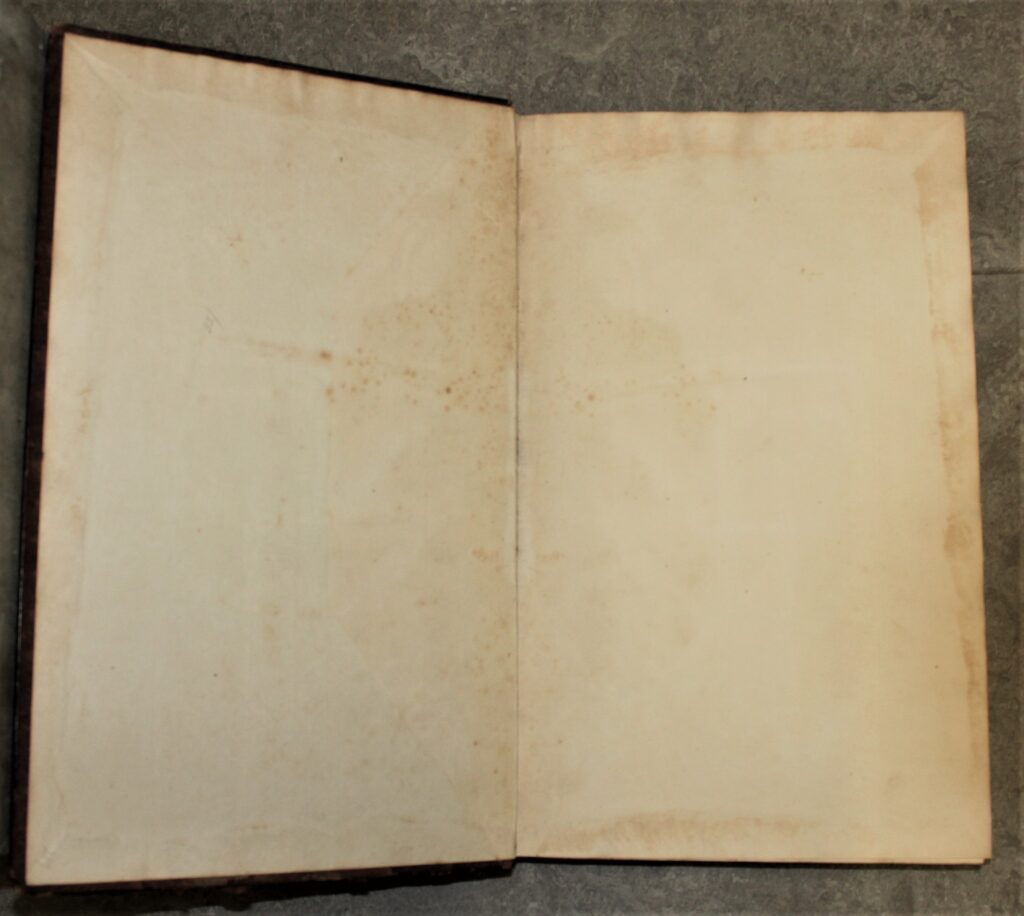

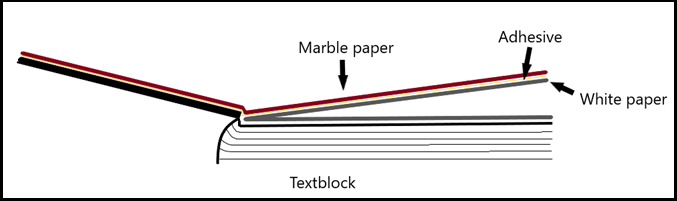

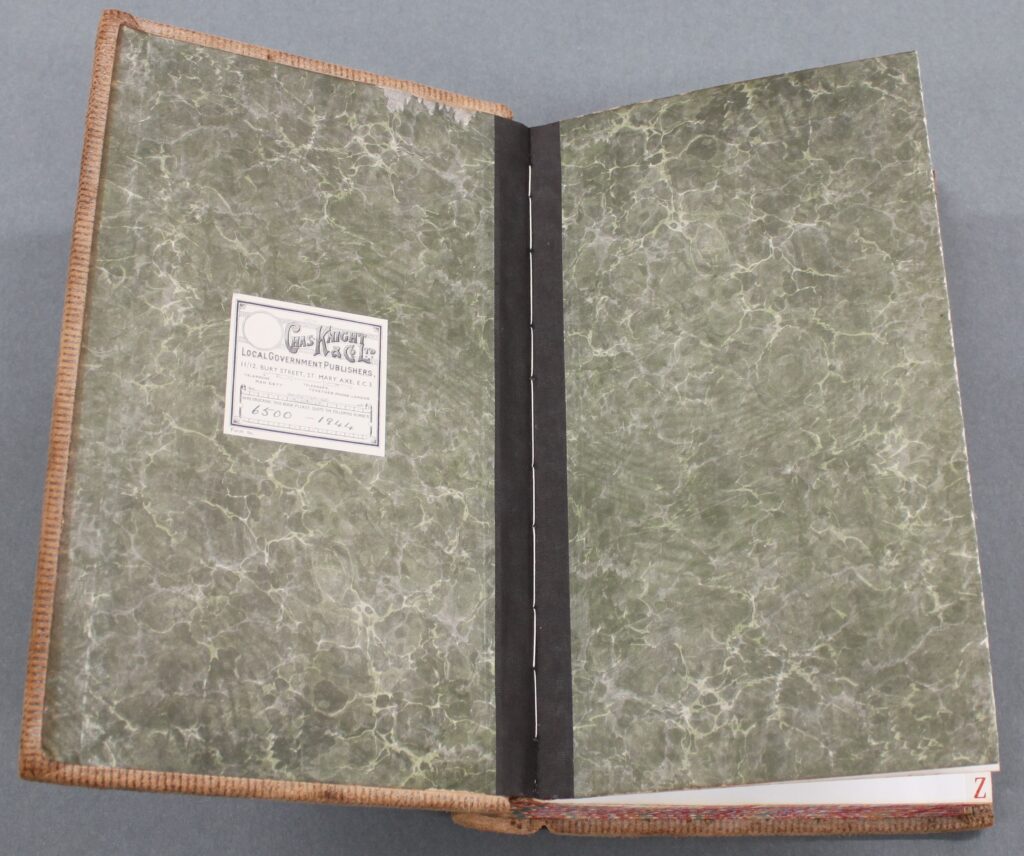

The ‘made’ endpaper is so called because the underside of marble paper is often marked from the making process with coloured drips or fingerprints and as such is not presentable enough to be visible. It is therefore lined with a folded sheet of white paper, creating a pastedown of marble, a marble/white flyleaf, followed by a white flyleaf. Whilst it is structurally sounder to sew this endpaper into the textblock, it can be simply pasted on. The ‘made’ endpaper can also be constructed with a cloth joint for additional strength, which is sewn along with the textblock.

A ‘made’ endpaper.

A ‘made’ endpaper.

—

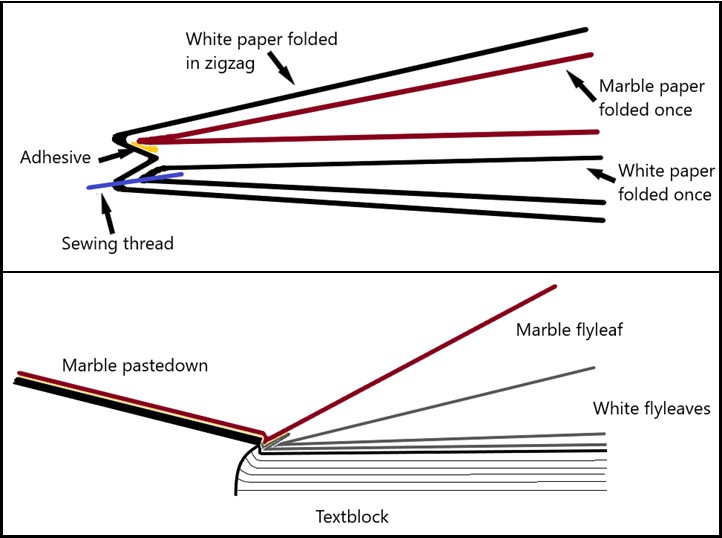

‘Zigzag’ endpapers require more work and are used for those bindings of greater quality. They consist of three sheets of paper: two white and one marble. One sheet of white and the marble paper is folded in half once, whilst the second white sheet is folded with a zigzag. The drawing shows their construction. They are made of the best quality paper and are always sewn onto the textblock. Their construction minimises the stress that is often exerted on the endpapers at the joint from continual opening and closing of the book. These endpapers can be adapted further to produce leather joints, doublures and silk or leather flyleaves. Doublure endpapers are created by forming a sunken area in the pastedown which is then inset with decorative leather, watered silk or decorative paper.

Endpapers have an important structural and protective purpose, but they can also provide great artistic opportunity. These days endpapers are often used to great effect, especially in children’s books, to build excitement, to delight and inspire.