In the local studies library at the Dorset History Centre you can find a large collection of journals. These journals are packed with fascinating articles and are often an underused resource. In this series of blogs we will be highlighting some of the interesting articles within them!

This is the seventh in our series of blogs looking at the journals held at the Dorset History Centre. In this blog we will be looking at two journals from the 1960s.

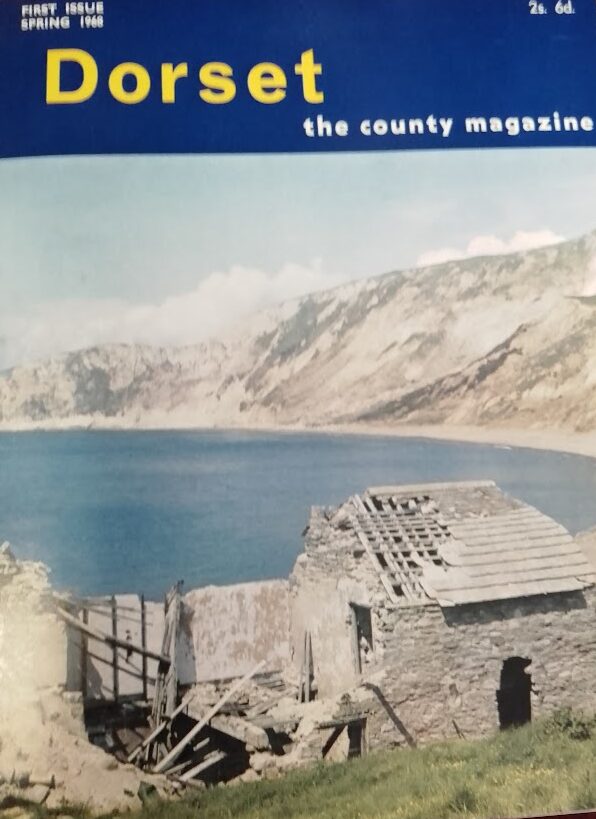

The first is The Dorset Magazine, a magazine that is still published today under the name Dorset Life. The magazine was started by Rodney Legg, who wrote many books on the history of Dorset. The first issue was published in 1968 and highlighted local environmental issues alongside features about the county and walks.

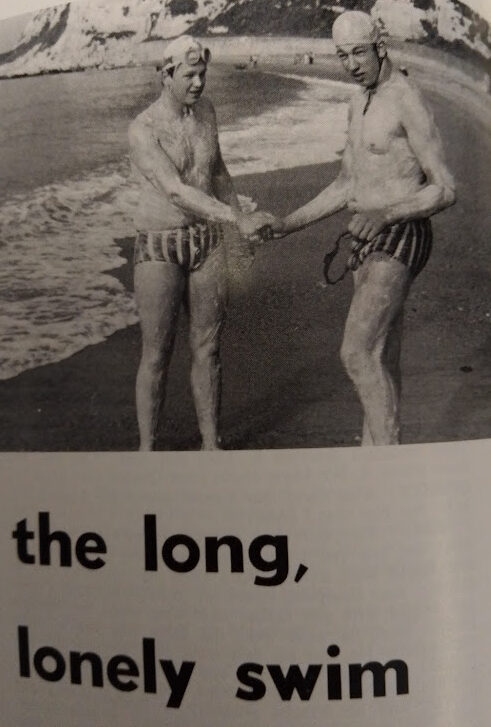

The article that caught our eye in this magazine is from the 7th issue from 1969. The article shows Phillip Gollop and Mervyn Sharp from Weymouth as they prepare for a record-breaking attempt to swim across the English Channel and back.

Phillip was twenty and had already swum the Channel on a number of occasions. His crossings in 1965 and 1967 made him the youngest person to swim the channel in both directions.

Mervyn had completed his first channel swim in 1967 and went on to make seven successful crossings.

The boys had to train in Yeovil as there was no swimming pool in Weymouth. Before the swim they were coated in grease and during the swim they planned to consume vast quantities of chicken, yoghurt, tinned fruit, coffee, chocolate, cheese sandwiches and steak.

According to the Channel Swimming Dover website both boys successfully made it across the channel on 6th August 1969, but didn’t manage the swim back to England.

—

The second journal that began in the 1960’s is the Journal of the Sherborne Historical Society. Unlike the glossy Dorset Magazine this journal is a small collection of typed articles. The article that this blog is focusing on is from the second issue from 1965.

The article contains extracts of the diary of merchant captain Richard Geen who was taken prisoner by the French during the Napoleonic war.

The diary was in the possession of Richard G Penman, his great great great grandson who, with Geen’s great great grandson Gerard G Penman, wrote an introduction to the transcription. The diary is described as

‘home made of folded blue writing paper stapled with a pin and a fragment of silk’.

The first entry is from Friday 15th November 1805 when Richard Geen was in ‘Lizerdiven’ identified as Lezardrieux in Portugal and the last is from Monday 28th January 1806 when he was in Stenney near Verdun, where there was a large depot for ‘gentle’ prisoners.

The introduction notes that:

‘over the period of the diary the prisoners stayed at thirty-three French towns or villages and marched more than 621 miles in shocking weather in a great arc through the northern borders of France, avoiding the Paris region.’

As a captain with money Geen had a better time than some of the prisoners. He was able to pay for extra food and better lodgings, but often worries about the condition of his crew, especially his brother in law, who had been captured with him. He also often complains about the price charged by the people who provide them with lodgings. On Sunday 24th November 1805 he writes of a female jailor, whom he describes as old and sorceress looking who ‘like all other French we had seen was affraid we should carry a little money out of the Goal in our pocket.’

The prisoners also had to contend with sharing jail cells with French prisoners and spending the night in cramped quarters. On the 29th November he writes:

‘There being no Town Goal so we ware all cram’d 31 in number into two small Cells each Room not more than 12 feet by 9 the place was horrible had no straw and stunk worse than a Hogsty – as thare was not Room for all to lay down at one time I Sat all night and was amus’d with the Cry of whose legs is this whose legs is this and as no person seem’d to own them I expected in Morning to find thare would be a great number of Leggs belonging to the Gaoler however our Company tok’d them all with them’

He also records having to deal with vermin infested cells and a Gaoler who left them standing in a yard in the snow from their arrival at 4 until dark.

Not all the Gaolers that Geen encountered were as bad. In a town called ‘Laval’ ‘the Goaler seem’d to be a Civel man considering his calling and his Wife put Plasters to our Blister’d feet and honour’d us with their Company at Supper, which we thought no small Honour in our present situation.’

On January 15th 1806 Geen and nine other masters were ordered to prepare to march to Verdun in two days time, which meant being separated from his brother in law and ‘his boys’. He is very upset by this, especially as three of his boys are in hospital and he thought ‘poor T’ Rumsem in a dying state’.

The diary ends on 28th of January, probably just before they reach Verdun. It isn’t known what happened to Geen after this, although it assumed he made it home as the diary had been passed to his family and the family have a miniature of him supposedly from 1816 or 17.

The extracts of the diary give a fascinating insight into how prisoners were treated in the Napoleonic wars and is just one of the hidden treasures you can find in our journals.

—

This is the sixth in our series looking at our academic journals. You can read other blogs by clicking on the link below: