We are always interested to hear about projects that are happening in our local communities. We’ve recently been pointed to the fascinating Slave Voyages Database, and links to Dorset. In this guest blog we take a look at the voyage of the Molly, charted in a fascinating new storymap…

—

More than thirty thousand slaving voyages are recorded in the Slave Voyages database, a little over 35% were undertaken by British flagged ships. There were some ten countries involved in the Atlantic trade, though of course, some present-day countries were not so constituted then. We associate this trade in people with Bristol, Liverpool and London, yet there were at least 30 ports around the British Isles directly involved in the trade at some point and many others which supported the trade.

Poole, Weymouth and Lyme Regis were hampered by tidal waters, exposure to gales or remote locations, so they never became major centres for the slave trade. Poole’s era of slave trading was in the mid-1700s. However, Dorset did have further connections with trading enslaved people, through the Newfoundland fisheries – a source of food for enslaved people on plantations. Dorset’s port’s wider connections can be explored through the digitised Lloyd’s Lists.

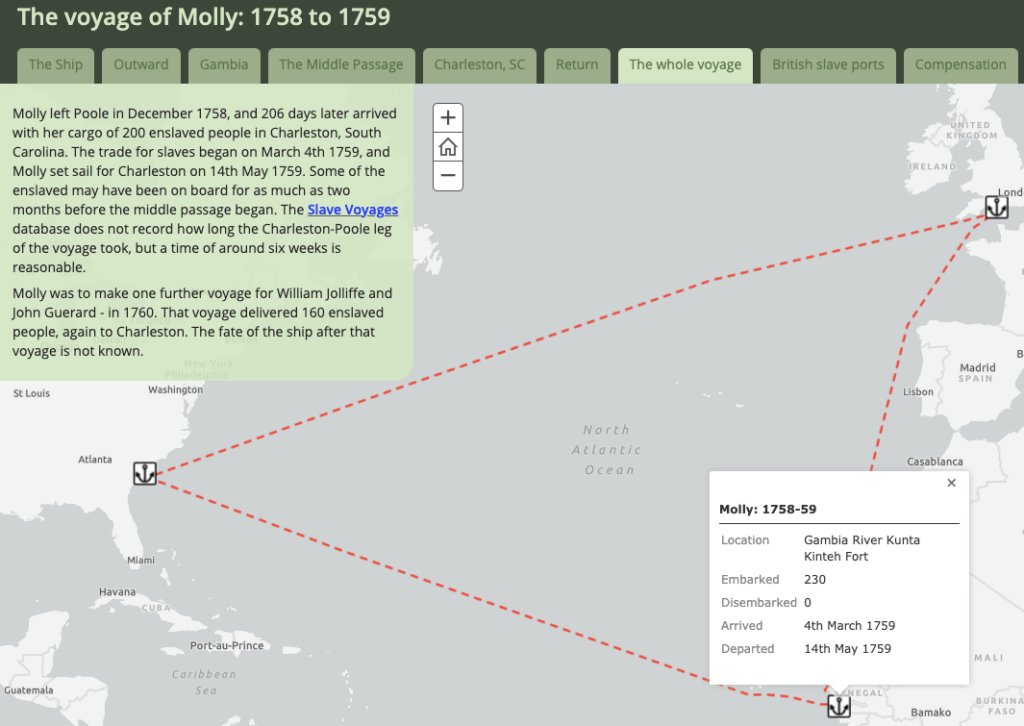

Much of this storymap’s basic detail can be found in the Slave Voyages database which itemises Molly’s itinerary. Molly – a ship obtained through an act of piracy – sailed in December 1758, possibly the fourth voyage made by that ship. As slaving vessels go, Molly was not particularly large, but refitting allowed 230 enslaved people, 25 crew and all of the provisions they needed to be carried on the Middle Passage. Enslaved people were often purchased in more than one location and many “batches,” necessitating a long and dangerous stay below decks for the early-purchased. It took around two months for Molly’s hold to be filled. The Middle Passage is stated as lasting 47 days, during which time 30 enslaved people died. By the time Molly arrived in Charleston, some of the enslaved may have been on board for more than 70 days. Once in Charleston, the enslaved would be auctioned.

Other voyages were made direct from Dorset to the American colonies, and, sometimes, they were made to re-export enslaved people from Caribbean islands to the American colonies.

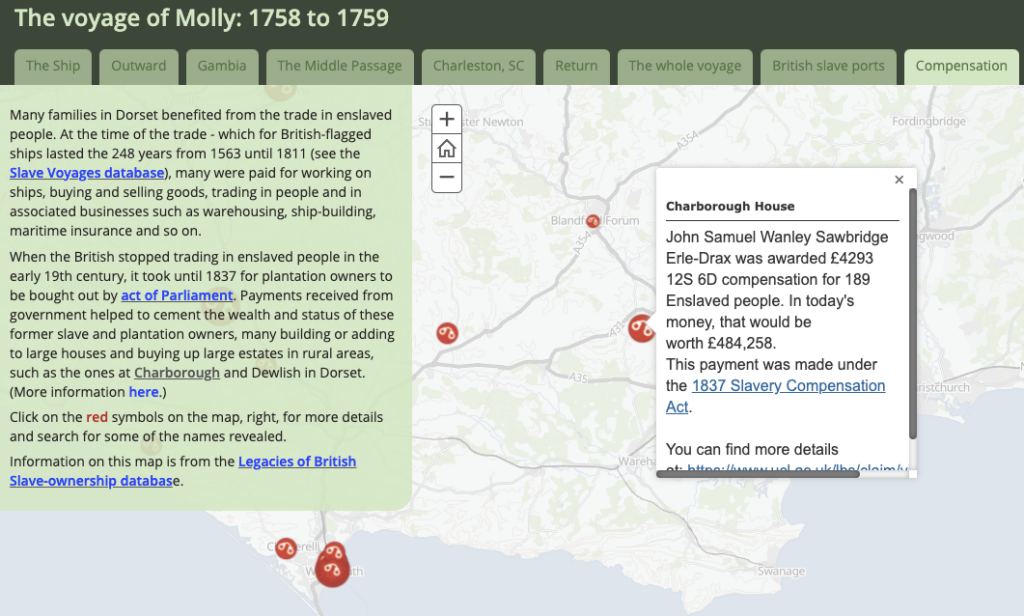

Dorset’s connection with enslavement is further detailed in the Legacies of British Slavery (LBS) database. Dorset was seen as a desirable rural area to which the slave-trade enriched could retire, so it is hardly surprising to find the LBS database has several listings for Dorset. Enclosure was driving people off the land, and large estates were all the rage. New “planter’ money could be used to buy status and even a seat in Parliament. Once abolished, a battle for compensation – for the owners and planters, but not the enslaved – began. The Slave Compensation Act paid out vast sums of money. A vast amount of taxpayers’ money was given by Act of Parliament to the often – but not exclusively – wealthy.

The idea for this storymap came from discussions with Jason Langford, a History teacher at Blandford School. The story of enslavement is too big to focus on, so we opted for one small local episode, which suggests links to the wider nature of this episode of Empire.

This was a guest blog written for Dorset History Centre by Steve Richardson. Between 1978 and 2016, Steve taught Geography in Skipton, Vancouver, Lyme Regis, Bristol and Blandford. On retiring, he worked for ESRI UK for six months in a dream geographer’s job – making maps online. He is currently a school governor, sourdough baker, runner and cyclist.