We have seen in previous blogs how sewing structures, endbands and endpapers can all affect how a book functions as a mechanical object. In this blog we’re going to take a look at books from a slightly different angle to see what the shape of a spine can tell us about a binding.

Look at a book that is open on a table from the correct angle and it will tell you a lot about its construction.

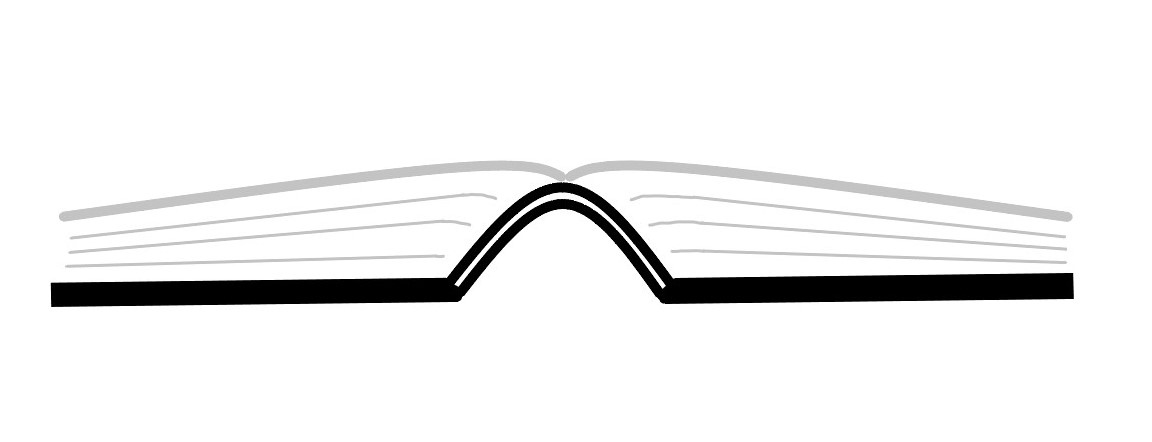

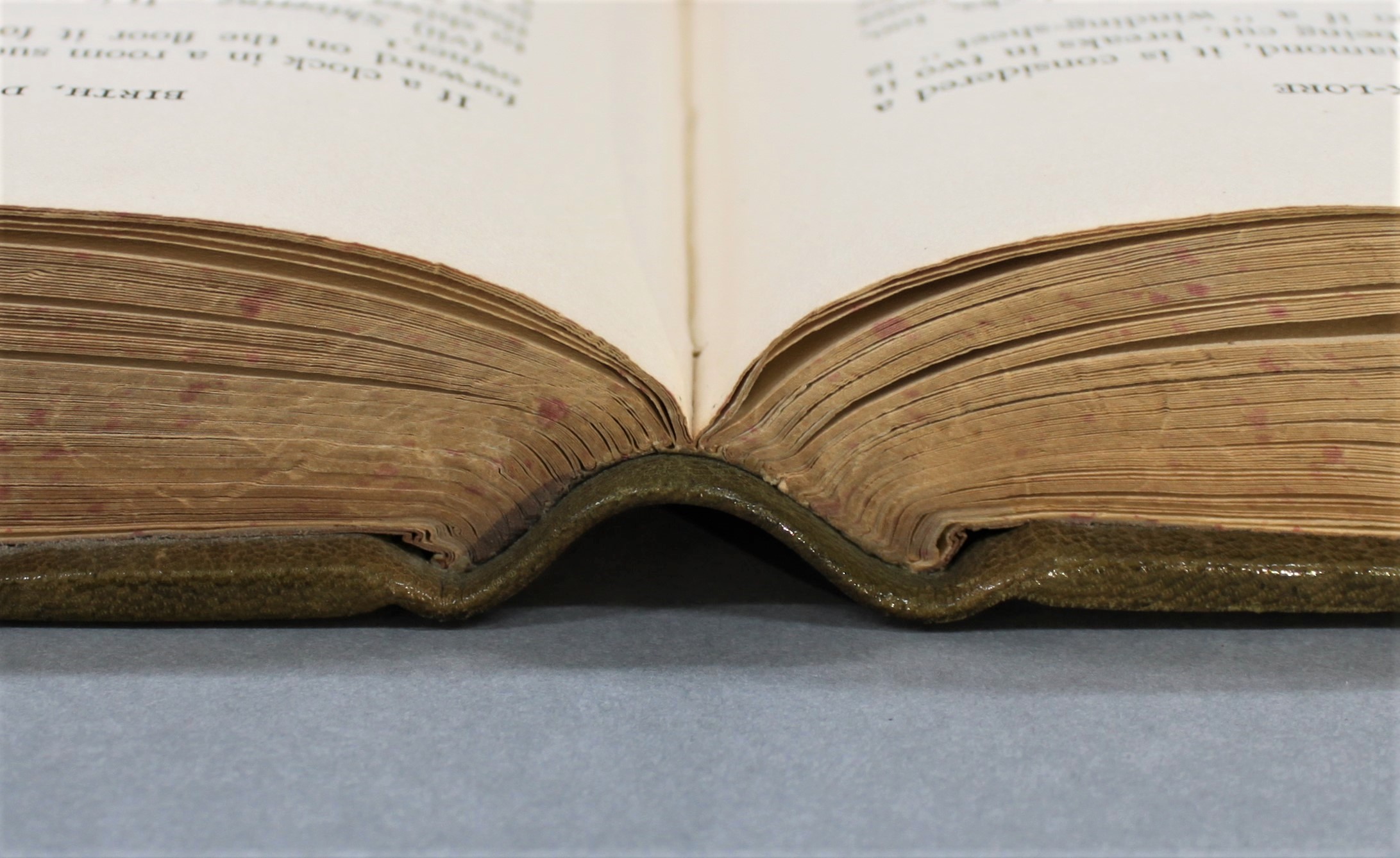

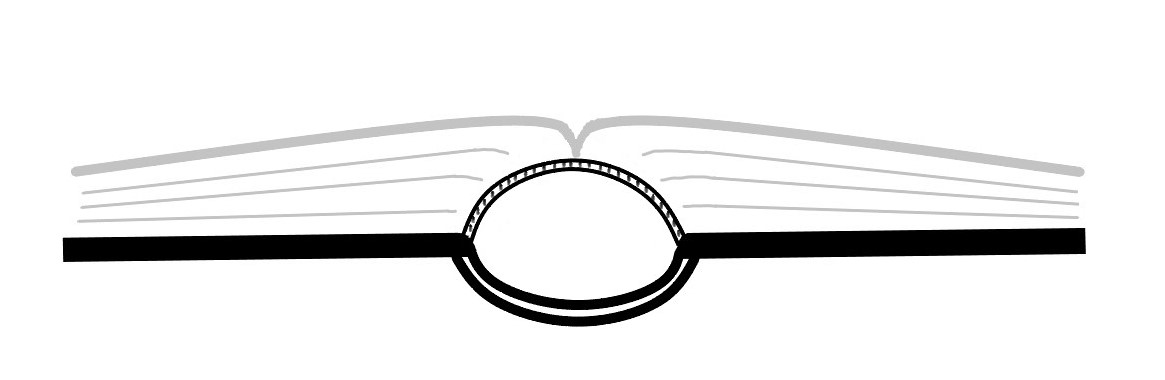

A ‘tight back’ binding is where the leather is adhered directly to the textblock. The spine will flex upwards when the book is opened, producing a concave shape. The leather is flexible and allows the textblock to open flat. However, over time small cracks will appear in the leather and any gold tooling on the spine can be dulled or lost.

—

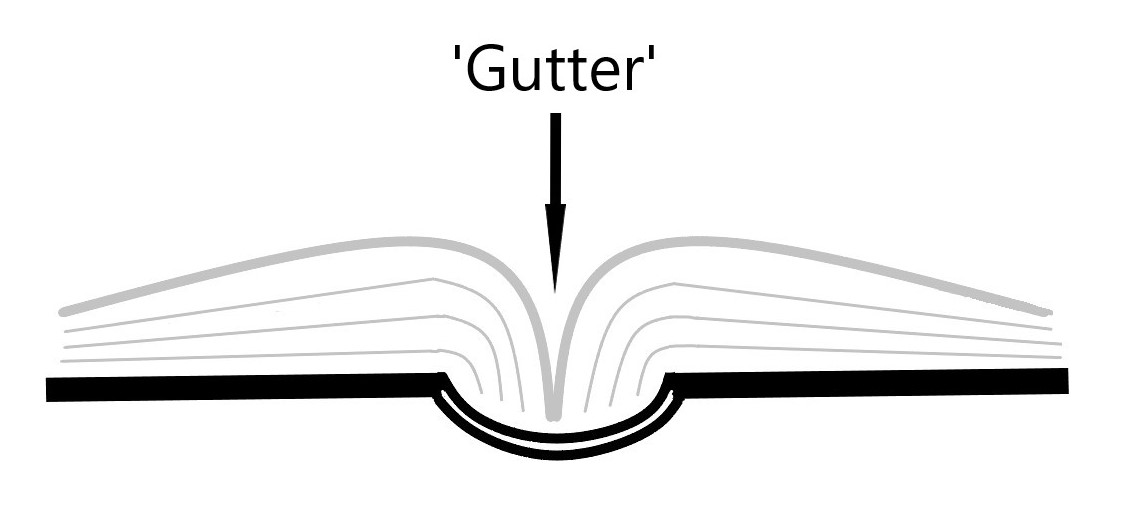

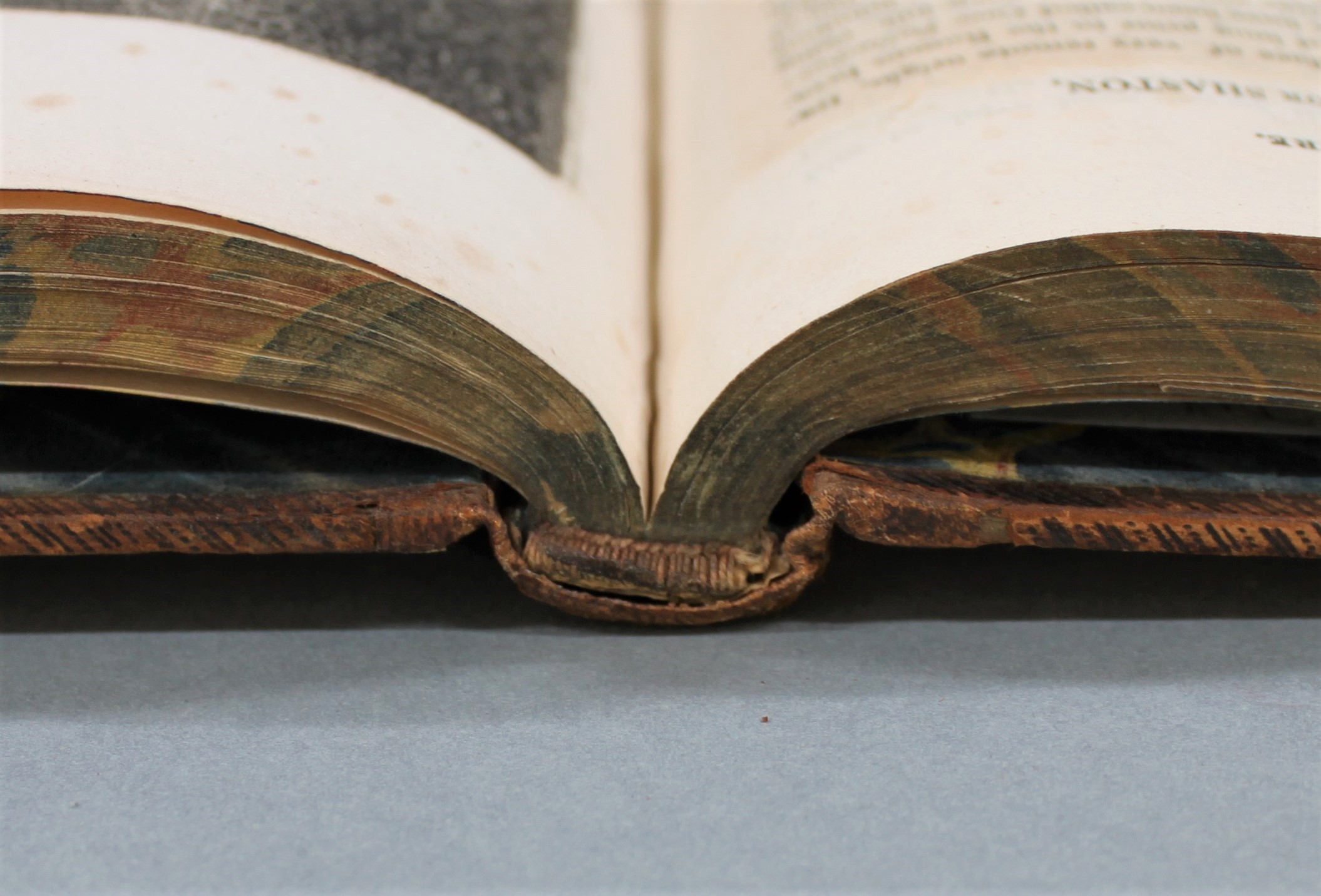

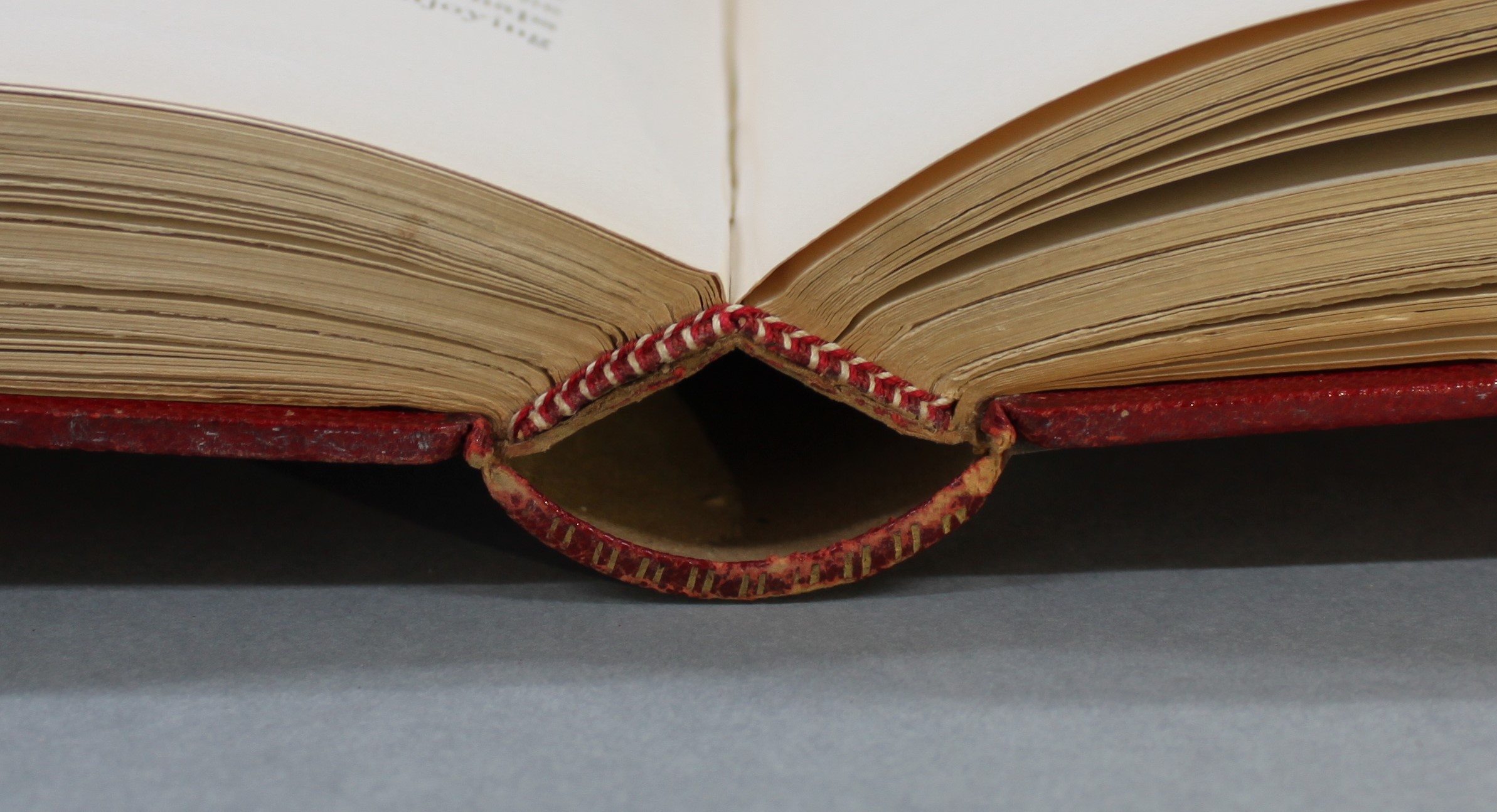

To prevent damage to gold tooling, binders began to line the spine with multiple layers of thick paper to produce a ‘stiff tight back’. The spine won’t change shape when the book is opened, but it also means the textblock cannot lie flat. The paper is forced upwards, creating a deep ‘gutter’, sometimes making text difficult to read. The structure is exposed to points of strain, often causing the binding to break.

—

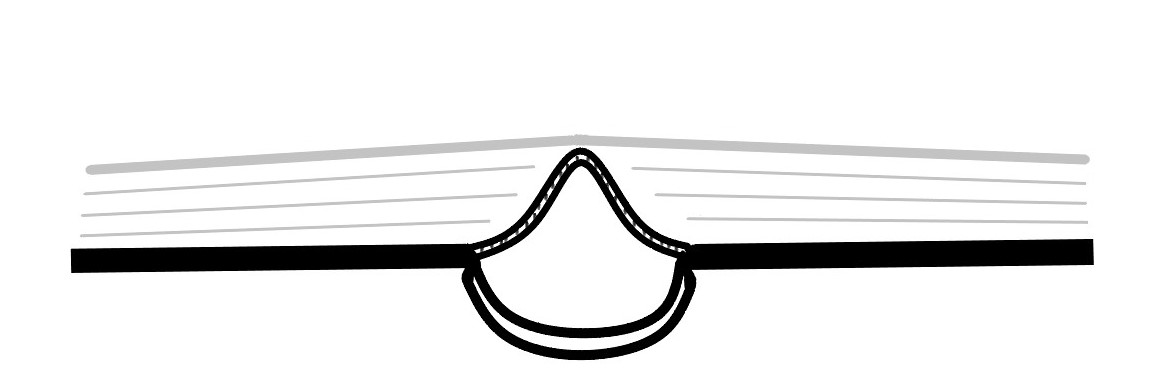

A ‘hollow’ binding was created to counteract this. A tube is made from paper the width of the spine and length of the boards, and is adhered to the textblock spine before being covered. When the book is opened the textblock is free to concave allowing the paper to lie flat, but the other side of the tube remains convex and rigid, protecting the gold tooling. This produces a ‘hollow’ which you can see through.

—

A ‘springback’ binding is an advancement of this design. When stationary bindings (volumes that were bought to be written in, such as ledgers or account books) became mass produced, this special construction was designed to ‘throw up’ the textblock, as seen in this video, so that it can lie flat, making it easier to write all the way into the fold.

—

If a conservator needs to ‘reback’ a book (that is, to replace the spine of a damaged book to prevent the book coming apart), it is important that they consider several aspects. They need to understand different spine structures, their method of construction, and how this affects the book mechanically. They also need to recognise the original binding construction and have an understanding of a books future use. All this information will dictate how the spine is repaired to best protect the book in the future as well as its historic context.