As part of his passion for physics, Purbeck School Sixth Form Student Max de Wit has been undertaking research on AEE Winfrith and helping Dorset History Centre to develop the historical record for the site. Recently, Max had the privilege of recording an oral history with Ian Upshall, whose working career was centred in the UK’s civil nuclear power industry. It was a fascinating insight into this unique and largely unsung part of Dorset’s history. The full recording is a rich and multifaceted personal and professional perspective and this blog captures a few highlights.

—

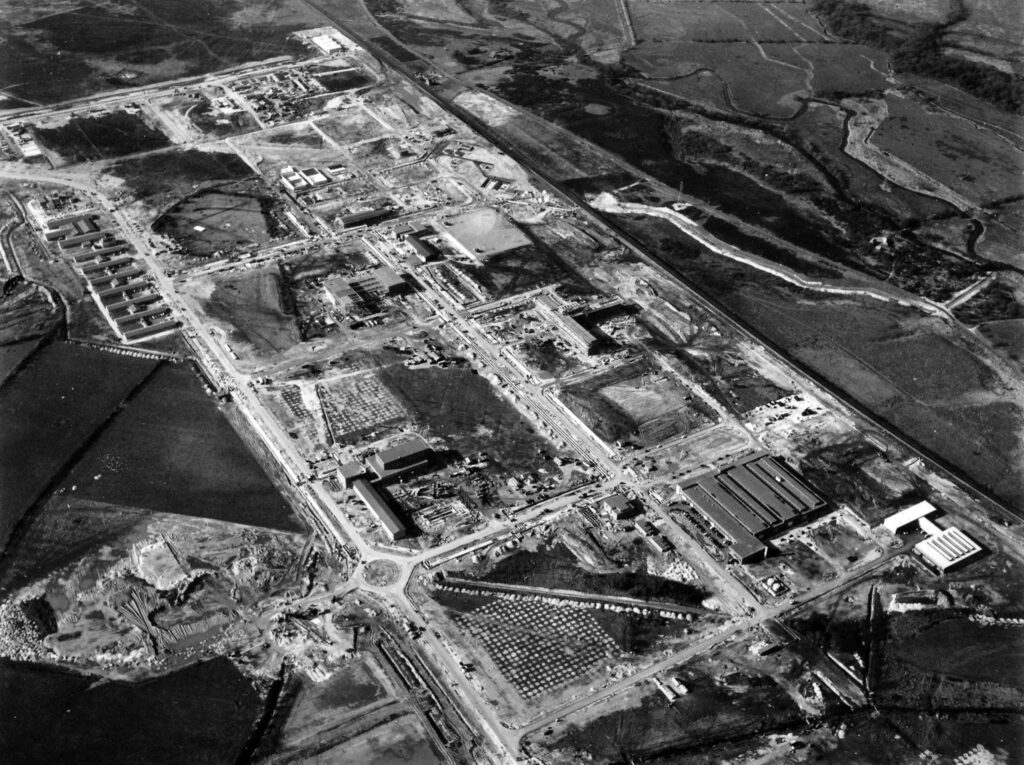

For many, the county of Dorset conjures bucolic images of wild heathland, windswept heights and unspoilt coastline; a deeply rural and traditional place, “unmoved, over many centuries” (Hardy, Return of the Native). But for over thirty years, tucked away on Winfrith Heath, midway between Weymouth and Bournemouth, just west of the village of Wool, the UK Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) operated a pioneering and progressive nuclear research and development facility, led by a Nobel prize winning physicist, which ushered in a golden age of nuclear research and science.

Ian Upshall was born in Dorchester and joined the Winfrith team when he was just 19, at a time when the government was vigorously pursuing the application of nuclear technology to the production of electricity. The eminent physicist, Sir John Cockcroft, was given the responsibility of finding a suitable area to develop this and Winfrith was chosen, due to the piles of rock that lay under the surface providing much needed support for potential infrastructure.

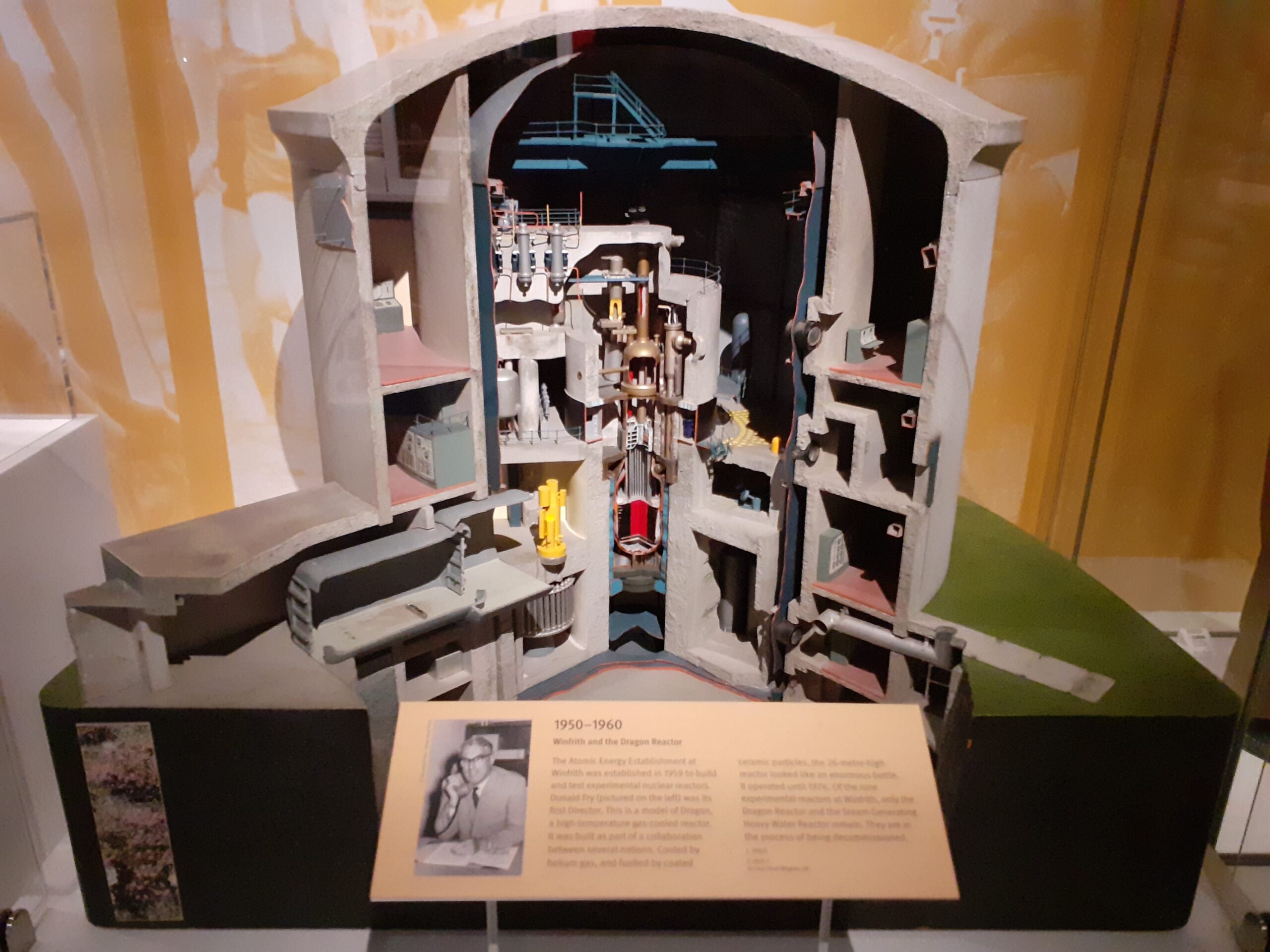

One of the first reactors at the site was the DRAGON reactor, which was a High Temperature Gas Cooled reactor (HTGCR) used to test fuel types. The helium cooled reactor initially used a golf ball sized spheres of uranium coated with carbon (in the form of graphite), with the graphite shell acting as a moderator. However, the ‘main reactor’ used while Ian worked at the plant was the SGHWR, which unlike most reactors in England of the time, was water cooled (as opposed to gas cooled). Connected to the grid in 1967, the reactor had a power output of about 100Mw (operating at about 30% efficiency), which is estimated to be enough power to sustain about 100,000 houses.

The core or calandria of this innovative reactor was comprised of 104 zirconium alloy tubes, used to hold the fuel elements (each being about 200kg of uranium). Cold heavy water was circulated to moderate these. A molecule of heavy water, much like standard water, is comprised to two hydrogens and an oxygen – however an isotope of hydrogen known as deuterium is used (resulting in a heavier nucleus, hence the name, allowing it to absorb more energy). This allows control over the magnitude of energy produced, the more heavy water is used, the more the neutrons are slowed and the more frequently fission reactions occur. These exothermic collisions then release heat, which is used to vaporise standard water, with the generated steam then removed by drums (with pressure of about 6200KPa), the steam is then passed through a turbine which spins an alternator, generating electricity. The reactor would operate for 9 months of the year, with the other three (in the summer, when electricity demand dropped) being used for maintenance and checks.

It was a core part of Ian’s role to undertake these vital checks. Every year 20% of the fuel would be emptied and the tubes would be scanned with ultrasonic to check for any cracks, as avoiding any leaks was of the upmost importance. When removed the fuel cells would still have some fission reactors occurring and when placed in water this would release a brilliant blue light known as Cherenkov radiation (apparently quite the sight to see). However, in the summer of 1990, it was decided that the reactor had fulfilled its useful life and the decommissioning process was initiated and continues to this day.

Ian then went on to work at Harwell and the safeguards authority (who monitored nuclear power stations over Europe to ensure no weaponry was being produced), before opening his own village shop and eventually retiring. Ian enjoyed his career tremendously and loved the fact that “no two days were ever the same”. Winfrith played an important role in the development of nuclear power for the entire nation and will hold an significant place in Dorset’s history.

—

This was a guest blog, written by Max de Wit, Sixth Form student at Purbeck School. If you would like to contribute a guest blog, please get in touch with us – archives@dorsetcouncil.gov.uk.