This account appeared in the Dorset County Chronicle on 16th June 1842:

Marshwood- Unlucky Accident- a young man of this parish had the misfortune, about a fortnight since, to cut off two of his fingers, with a hook, whilst engaged in chopping a stake to assist him to carry his box home from his late master’s, whose employ he had left for the purpose of being united in the sweet bands of Hymen, to a stout and ruddy nymph who would have given grace to any niche in the temple of beauty. The anxious bridegroom had taken a house, and everything was “settled” for the wedding: as might have been expected he was very much troubled on account of losing his fingers, but, alas! what agonising torment was added to this calamity, when, on his ill-natured and cruel Hera being made acquainted with the misfortune, she, instead of sympathising with her ‘lover’, actually told him, point- blank, that she would never marry a piece of a man! This Amazonian rebuff and unkindness has almost driven poor Lubin to madness; but, being determined to revenge the slight of his faithless bride, our young hero became enamoured of another gay and lively lass, about eighteen. who, although not without “incumbrance”, attracted his notice.- After renewing his tale of love, and boldly ‘popping the question’, his offer was accepted, and, determining now to “take time by the forelock”, he went forthwith, accompanied by his less scrupulous second sweetheart, to the parish clerk, who was called up when midnight had nearly arrived, to receive notice for the banns, which were duly published the next day in the mother church of Whitechurch.

The reporter takes a rather malicious glee in mocking the characters involved with this incident – using flowery language and references to the classics which may have raised chortles amongst the educated class but were unlikely to be understood by the participants in these unfortunate and dramatic events.

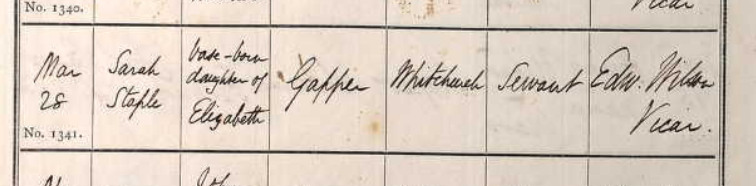

What can we discover about the people in the report? The only wedding that took place at that time was between Elizabeth Gapper and Robert Turner. Elizabeth had an illegitimate child, the ‘incumbrance’ referred to. We can see her daughter Sarah’s baptism in 1841 in this parish record for Whitechurch Canonicorum – so she would have been a very young child at the time of her mother’s marriage, and the 1841 census shows Elizabeth and Sarah living with Elizabeth’s parents and siblings.

This tale is full of unusual records though – before the marriage of Robert and Elizabeth, the small church at Whitchurch Canonicorum heard two sets of banns read within a few weeks – and both are for Robert Turner and Elizabeth Gapper! In fact, two Elizabeth Gappers were born in the village who at the date of the wedding were twenty-five and nineteen respectively. It looks likely that Robert’s first love, who rejected this ‘piece of a man’ and the ‘gay and lively lass’ who married him were both called Elizabeth Gapper.

However, by 1851 Elizabeth had remarried, to James Staple, probable father of baby Sarah. When Sarah herself marries, in 1865, at the age of 25, she gives her name as Sarah Staple Gapper, and names James Staple as her father. As James was a Mason, its possible that his work moved him from place to place and that back in 1841 he had left Elizabeth and baby Sarah behind – leading her to marry Robert Turner the following year.

In 1848, when Sarah was seven, her mother and James Staple had banns read in Whitchurch Canonicorum church to announce their plans to marry. Elizabeth declared herself a widow. We have been unable to find any records for her first husband, Robert Turner, after their marriage back in 1842. However, the actual marriage between Elizabeth and James did not take place until the following year – and not in Whitchurch Canonicorum, but in Ilmister, over the border into Somerset. Was the marriage delayed because local people knew that Elizabeth was not a widow? Did the couple move away to marry to escape this knowledge? At the time of their marriage, James Staple is still a Mason, following in his father’s footsteps, and Elizabeth’s profession is given as dressmaker. She also appears on the census as a dressmaker or sometimes a milliner (hat maker). In the days before ‘off the peg’ clothes, most women had to sew their own garments or provide fabric and discuss the desired pattern with a dressmaker, so this was a steady type of income and could be carried out at home whilst watching out for young children.

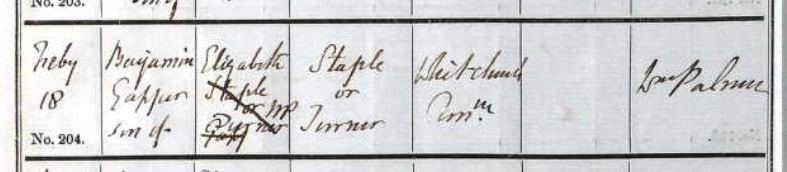

By 1855 Elizabeth was living back in Whitchurch Canonicorum and she had a child baptised – Benjamin Gapper. As with ‘Sarah Staple’ Elizabeth likes to use a significant surname as a middle name. At the baptism there is confusion about both Elizabeth’s surname, and the child’s. As you can see in this unusual entry in the parish register, ‘Staple’, Turner’ and the start of ‘Gapper’ have all been crossed out as surnames for Elizabeth – she is left rather nameless! Her son is given the surname ‘Staple’ OR ‘Turner’!

Does the incumbent at Whitchurch Canonicorum know that Elizabeth’s first marriage was to Robert Turner and that James Staple is not her true husband? No father’s name is given as such – was James Staple away working as a mason? Or was he avoiding the awkwardness of attending the baptism and providing his details for the register?

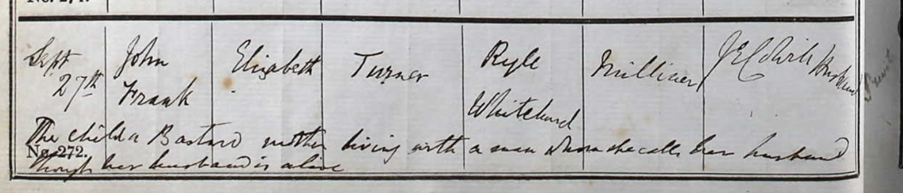

Perhaps so, because two years later- when another son, John Frank, is baptised – the Vicar has explained the situation more fully writing,

‘The child a Bastard mother living with a man whom she calls her husband though her husband is alive’.

Again, Elizabeth is the only parent named- working now as milliner (hat maker). We can only imagine the social awkwardness surrounding Elizabeth’s determination to have her children baptised.

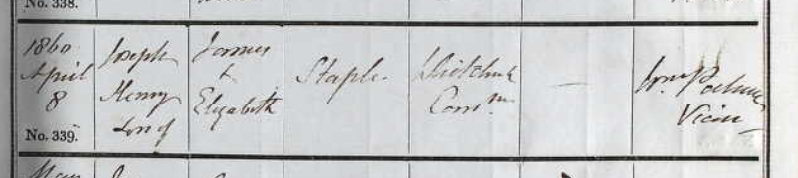

In April 1860 James and Elizabeth were blessed with another son, Joseph Henry. At this baptism both parents were named – James and Elizabeth Staple – and no additional remarks!

In the 1861 census we find another anomaly – on Ancestry the Head of the household is listed as ‘James Elizabeth Staple’ – living with her twenty-year-old daughter Sarah and four sons. But a closer look at the census sheet shows that that both ‘James’ and ‘Elizabeth’ have been crossed out – then Elizabeth Staple written in. Was James working away again? We know that Elizabeth was literate so probably completed the census return herself, and perhaps wondered at first if James was Head of the house, then realised that it was a record of those actually at home on just one night. Elizabeth is a dressmaker, and her daughter Sarah is a ‘stay maker’ – ie she makes corsets and girdles, stiffened supports to control the female figure!

James Staple died aged fifty in 1870. After his death Elizabeth moved her family to Gloucestershire and was living with her four sons and a daughter of nine at the time of the 1871 census. Ten years later she was living with her youngest daughter and her husband. She died at the age of fifty-three and her status was given as a widow.

Meanwhile – what of the vanished Robert Turner, two fingers short and missing from the record after his marriage to Elizabeth in 1842? No conclusive evidence can be found – but intriguingly in 1852 a Robert Turner was convicted of burglary at the Dorset Assizes. This was around the time that Elizabeth began presenting herself as a ‘widow’ and married James Staple. Robert was considered to be a ‘criminal lunatic’, found ‘wandering at large’ so his sentence of seven years transportation was replaced by removal to Broadmoor in Hampshire.

He was moved to the Dorset County Lunatic Asylum (later Herrison Hospital) in March 1868 and his age then was given as forty-three. If this is accurate, he would have been only sixteen or seventeen when he married Elizabeth Gapper, with her ‘incumberance’ in 1842. This was legal, but would the nineteen-year-old Elizabeth have married a younger man? If he had a home ready for her and her child, it’s possible that she would have seized this chance to leave home and Robert may not have owned up to his youth when they wed. The Robert who was convicted was a ‘seaman’ – which might also explain his absence from the census, but it’s unlikely that this mystery can ever be fully explained.