The Poor Laws existed in England and Wales between the late 16th century and the 20th century in some form or another. Before their introduction, beggars and vagrancy were increasingly viewed as a problem that needed to be dealt with, so a system was created to help the ‘deserving poor’ and punish the ‘undeserving poor’ (at least in theory! The execution varied on a case by case basis).

There are a few broad stages we can consider the Poor Laws to exist in, and the one we’re discussing today is the Old Poor Law, or the Elizabethan Poor Law. This created a system organised by individual parishes to administer relief, and the people who enacted this were called the Overseers of the Poor.

This was an unpaid position working under a Justice of the Peace (effectively a judicial officer) that would have been assigned to you, so naturally many were not happy in their role.

The supposed advantage of this local level of administration was that in small towns and villages, everyone knew everyone else, and the Overseers should be able to determine who were the ‘deserving poor’ and who were the ‘undeserving poor’. This distinction was largely based on if they were considered able to work. However, it would likely also have been based on the individual’s relationship with the Overseer.

So what form would your ‘relief’ take? Most commonly it would just be money or goods, it could include being taken to an alms house if you were elderly, but alms houses were usually private charitable establishments.

By the mid-18th century, the system was changed to deal with the population increase and the greater degree of mobility people had.

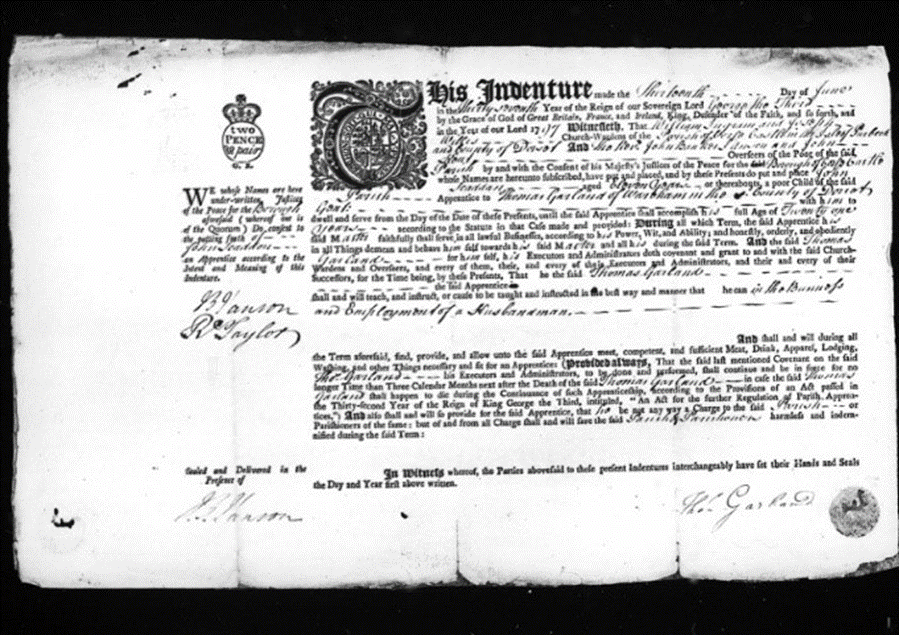

The Overseers of the Poor were also responsible for the creation of indentures for apprenticeships, and usually two would sign these records between the two parties. These were printed, and had spaces left blank for the parties to write in, or have written in on their behalf, names and figures. This leads one to believe that these were common documents, and it was therefore a very common practice to have a child of a poor family apprenticed in some craft.

Indeed, you can find many of these quite easily in the Dorset History Centre on microfilm. For example, we’ve picked out an indenture for an apprenticeship in the Wareham area, which was dated 13 June 1797 for a John Scaddan.

The Poor Laws would change in the 1830s and start being phased out as more modern systems became available in the late 19th and 20th centuries with liberal welfare reforms, but it is interesting to see how welfare has developed in this country over the centuries.

As a side note, where documents have been very useful in shedding light on the past, many of these naturally were created by people who could read and write, and certainly prior to the 19th century, those people tended to be richer. For that reason, documents like this can sometimes be the only stepping stone between someone’s birth, a possible marriage, and eventual passing, making them even more valuable for us.

Stay tuned for another blog from Molly, exploring the life of a young apprentice in Lyme Regis, coming soon!

—

Further Reading

Bloy, Marjie. “The 1601 Elizabethan Poor Law.” The Victorian Web. Last modified 12 November 2002. Accessed on 23 June 2023. https://victorianweb.org/history/poorlaw/elizpl.html

Kussmaul, Ann S. “Servants in Husbandry in Early Modern England.” The Journal of Economic History 39, no. 1 (1979): 329–31.

“Poverty and the Poor Law.” UK Parliament. Accessed on 23 June 2023. https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/livinglearning/19thcentury/overview/poverty/

Overseers of the Poor Account Books, Dorset History Centre.

Poor Relief and Charity, Dorset History Centre.

—

This has been a guest blog written by Ben Corben-Hale, who spent four weeks at Dorset History Centre doing work experience. If you would like to contribute a guest blog for publication, please get in touch: archives@dorsetcouncil.gov.uk