In January 2024 Dorset History Centre will be undertaking two collections weeks and we will be closed to the public for this period.

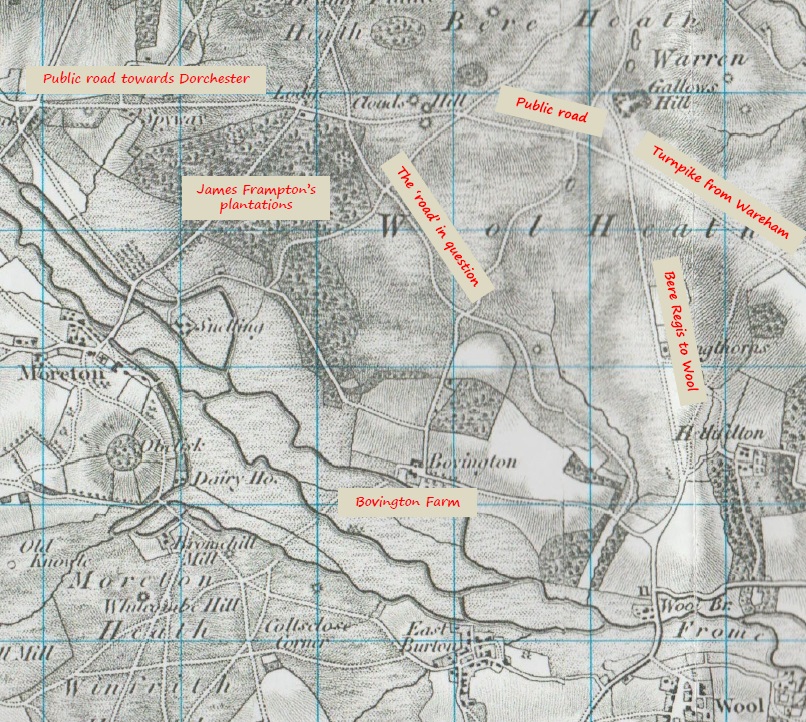

Whilst staff and volunteers will be getting on with the important work we have to do during this period, we have this two-part guest blog for our readers, from Martin Gething. On Monday Martin explained how James Frampton found himself in trouble with the law. As a reminder, James Kellaway, a labourer on Bovington Farm (which was not part of Frampton’s property), was not happy with the state of the path, and, egged on by an attorney based in Wool named John Carter, brought a complaint against Frampton that he was ‘not maintaining the public highway’.

Today, Martin looks at what happened next for Frampton and the law…

—

Rule challenged

A challenge to the Rule was indeed presented on behalf of the prosecution, on 8 May, contending that Frampton was “not entitled to be discharged from the indictment upon the production of a certificate of two justices and affidavits, which merely state that ‘the road is now in repair;’ they should shew something done since the finding of the jury.”

However, this was over-ruled by the judge as the prosecution could not provide any evidence that the road was not repaired, and so James Frampton’s discharge from any further requirement was confirmed.[1]

The Enlarged Rule

Surprisingly, it appears that the discharge resulted in the whole indictment being dropped retrospectively, meaning that Frampton would have a completely clear ‘criminal record’.

The justification was that his legal team considered the main instigator to be John Carter (age about 40, Attorney and Small Farmer in Wool), and that James Kellaway (age about 70, Agricultural Labourer living in Wool) had been persuaded to join in (‘procured’) by Mr Carter. The defence team’s briefing notes making this clear:

The Prosecutor Kellaway is a person procured by Mr Carter and a Man of Straw for the purpose of this Indictment and Mr Carter is a Gentleman who served his Clerkship in an Attorney’s Office and has been Admitted, but he resides in the Village of Wool where he Farms a Small Lifehold Property which he holds under Mr Weld.[2]

Further, Frampton’s team asserted that John Carter’s complaint was ‘vexatious’, and this aspect resulted in a modification to Case Law. In the Eighth Report of Her Majesty’s Commissioners on Criminal Law, Chapter XI, Section 3 relates to ‘Costs of Prosecutions’. [3]

Article 30 of Section 3 (below, with emphasis added) basically says in some cases the prosecution’s costs must be paid by the defendant (as we might expect), but there were also circumstances when the defence’s costs should be paid by the prosecution (even though the defendant was found ‘guilty’) if the prosecution was considered to be vexatious:

Article 30: The court before whom any indictment or presentment shall be tried for not repairing bridges, or the roads at the end thereof, repaired at the expense of the county, may award costs to the prosecutor, to be paid by the person or persons so indicted or prosecuted, if it shall appear to the said court that the defence made to such indictment or presentment was frivolous, or may award costs to the person indicted or prosecuted, to be paid by the prosecutor, if it shall appear to the said court that such prosecution was vexatious.

The modification to Article 30 arising from the Queen v. Frampton case was that instead of just awarding costs to the defence, the court could rule that the whole indictment should be ‘removed’:

Article 35: The provisions of Article 30 include those of preferring and removing the indictment. (k)

where reference ‘(k)’ is the Queen v. Frampton, 1843 case.

Final outcome

Thus, James Frampton had the whole indictment retrospectively dropped, and in the process had a new ‘Article’ added to Case Law. Clearing his name was no doubt of great importance to Frampton, as he was a local magistrate himself and a member of the Grand Jury at the Dorset Assizes.

Postscript

Incidentally, James Frampton was probably right that Mr Carter was being vexatious – in the Dorset History Centre archives there is a lengthy set of correspondence from June 1847 to June 1849 between the two of them, regarding a path from Winfrith to Bovington, and a bridge over the River Frome, which Carter accused Frampton of obstructing. Mr Frampton wrote for help to Carter’s landlord, Joseph Weld, Esquire, of Lulworth Castle. Mr Weld wrote a very pleasant letter back, saying it was nothing to do with him but he was on Frampton’s side as he also found Carter troublesome! [4]

—

[1] Reports of New Magistrates’ Cases … From Easter Term 1844 to Trinity Term 1846. Google Books: https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/_/9lcDAAAAQAAJ , page 29.

[2] See Footnote 1.

[3] Google Books: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=ARRcAAAAQAAJ, page 202.

[4] Dorset History Centre, D-FRA/E/22, Correspondence concerning disputed footpath and road from Winfrith to Bere Regis through Bovington Farm from Messrs. Coombs and Joseph Weld and copy letters from J. W. Carter and James and Henry Frampton, with memorandum, 1847-49.