It could be said that most people take their surnames for granted. Perhaps those of us who spend time looking at our family history are more familiar with them than others, as we are often to be found scouring through records for particular names, paying close attention to spelling and cursing incorrect transcriptions! But how often do we stop to think about where these names came from?

According to J.W. Freeman’s book, Discovering Surnames, which can be found in our Local Studies Library (shelf mark 929.420941), the use of surnames began with our Anglo-Saxon ancestors. Originally, they were nicknames, tacked on to forenames to make distinguishing between people easier. Someone might be known as ‘Eric the Red’ to differentiate them from ‘Eric the Bold’. Over time these nicknames developed into the surnames we know today. As such, surnames can tell us a lot about our ancestors. It might be evidence of where they came from, what job they did, their appearance or even their personality!

Perhaps you know someone with the surname Heron, for example. This – perhaps unsurprisingly – was once a nickname for a thin man with long legs. Bassett, on the other hand, referred to a man of low stature. Breakspeare was not, as you might think, a clumsy man, but rather a victor in a tournament where the winner had broken the spear or lance of his opponent. Moneypenny, made famous by the James Bond books and films, was once a nickname given to a rich man or, ironically, a poor one!

Many surnames are of course derived from trades or occupations. Almost everyone knows someone with the surname Smith, which comes from the Old English smid, meaning blacksmith or farrier. Every village in medieval England had a smith, so it is no wonder that the surname is so pervasive today. Similarly, Turner comes from the French word tornour, referring to someone who fashioned objects of wood, metal or bone on a lathe, while Wainwright grew out of the Saxon waegnwyrtha, meaning wagon builder.

Other names refer to family relationships, the most obvious being those that end with -son. Robertson originally meant son of Robert, Johnson son of John, and so on. Other relationships are harder to spot. For example, you would be forgiven for thinking that Gossip was a derogatory name given to someone who talked behind peoples’ backs, but in fact it comes from the Old English word godsibb meaning ‘godfather’ or ‘godmother’.

Many surnames have roots in the French language, thanks to the Norman Conquest. Verity, for example, was taken from the French verité, meaning truth. The French word paien, from the Latin paganus, originally referred to a villager or rustic, but later came to mean heathen or person of no faith. Numerous surnames have grown out it, including Paine, Payen, Pagan and Paynes. In the early days, such a surname was given to children whose baptisms had been delayed, or to those whose religious zeal was not as fervent as it should have been.

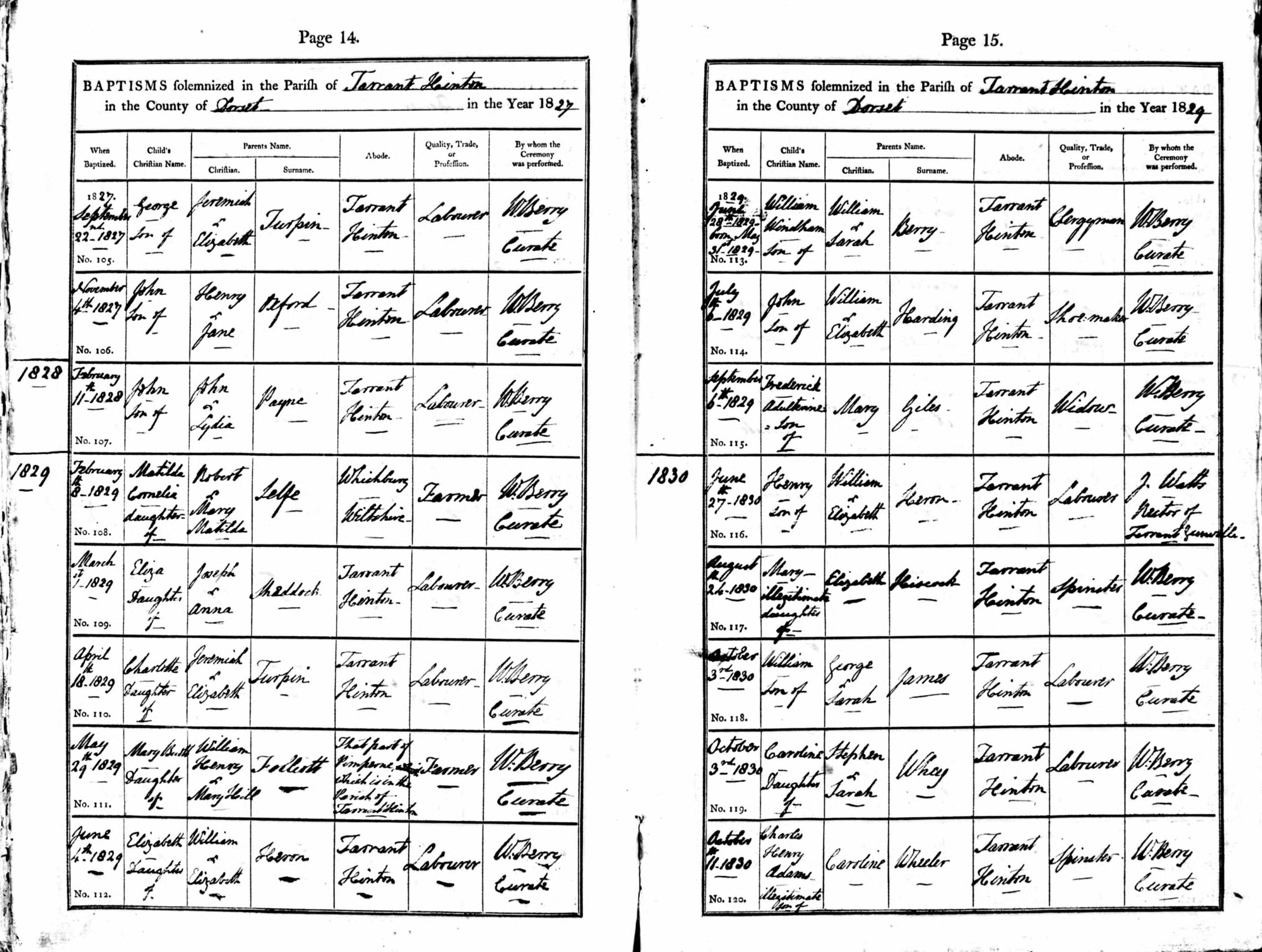

In Tarrant Hinton in the 1820s and 1830s, there was a family of Herons living alongside a family of Paynes. No points for guessing where the ancestors of John Oxford came from, but you might be forgiven for not knowing that the ancestors of Eliza Maddock likely came from Wales, as her surname derives from the Welsh word madog, meaning goodly (PE-TTH/RE/2/1).

Surnames that relate to places are amongst the most common of all surnames. They would once have indicated where a person lived, sometimes in a general sense – Wood, Marsh, Hill – and sometimes in a very specific sense, referring to villages, farms, manors, or even single houses. If you have ancestors with the surname English, it is likely that they came from areas near the borders with Scotland and Wales, Lincolnshire and Yorkshire, or Essex, Kent, and Sussex. Near the borders the name was given to a native of England, in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire it was given to those who refused to adopt Danish customs, and in Essex, Kent, and Sussex it was used to distinguish the local population from the Normans.

These are just a few of the names that can be found in J.W. Freeman’s book, as well as A Dictionary of British Surnames by P.H. Reaney which can also be found in our library (shelf mark 929.42). Perhaps you have people with these names amongst your ancestors, or maybe you even hold one yourself! If you are interested in finding out more about surnames, why not visit our library, or have a go at uncovering your family tree with Ancestry, which is free to use at Dorset History Centre.