Returning to our exploration of a nineteenth-century diary, readers can find themselves back again navigating Berry and Helen’s experience of Victorian Winterbourne St. Martins. If you missed the introduction to our new series on this illustrated and handwritten Victorian journal, you can find it here.

After an eventful entry into Winterbourn St. Martins as their carriage travelled through a deep flood, Berry adds further drawings and descriptions to convey her arrival.

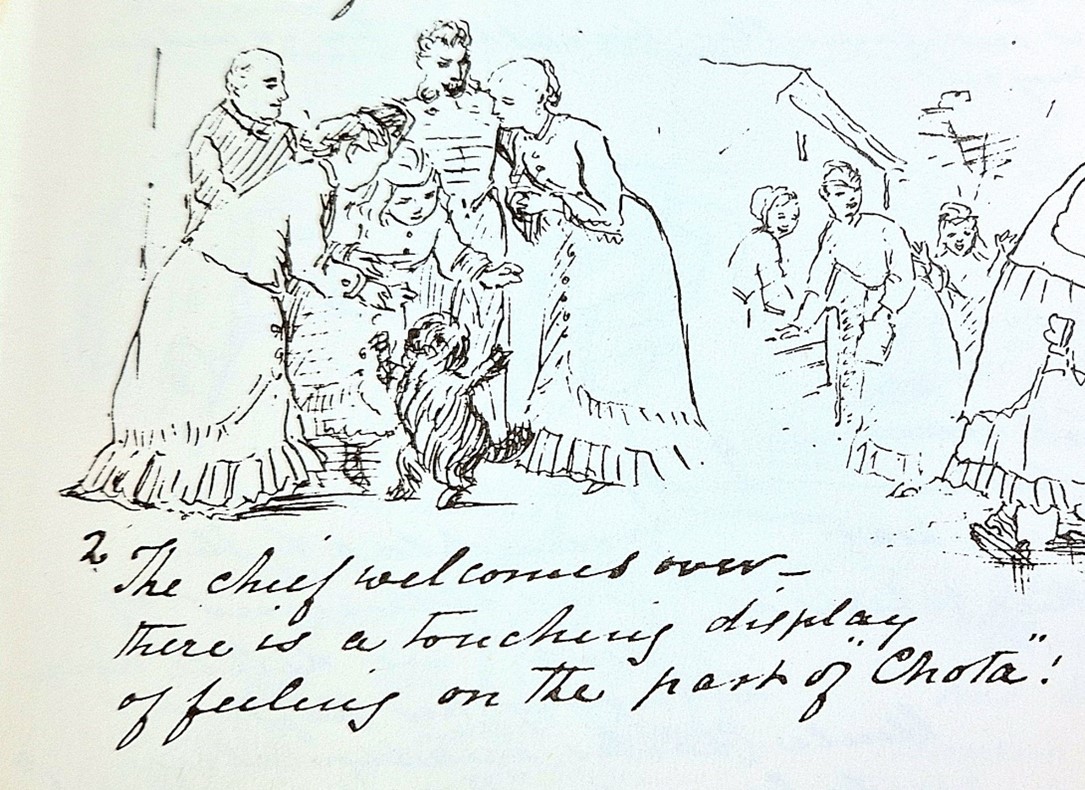

A dog appears to stand on its hind legs in greeting to a crowd of people.

Berry writes beneath the image,

The chief welcomes over – there is a touching display of feeling on the part of ‘Chota’!

Here, readers are introduced to the Clapcott family dog. Named ‘Chota’, the dog makes many appearances throughout the journal. Although one cannot be quite sure, it appears that the dog could be related to the terrier breed.

Jo Draper, conducting research for the Dorset Natural History & Archaeological Society on the journal, offers useful information here. According to her commentary added to the back of the journal, “‘Chota’” means small in Anglo-Indian – it comes from Hindi. Dogs play a prominent part in this journal” (pg. 52). “Chota” also appears to mean “small” in Punjabi.

No doubt various questions arise about the family dog. “Chota” is a unique name for a family dog living in rural Dorset. Why was the dog given that name?

Why “Chota”?

During our research, it became increasingly clear that what may appear as innocent may actually be tied to a deeply problematic and violent history.

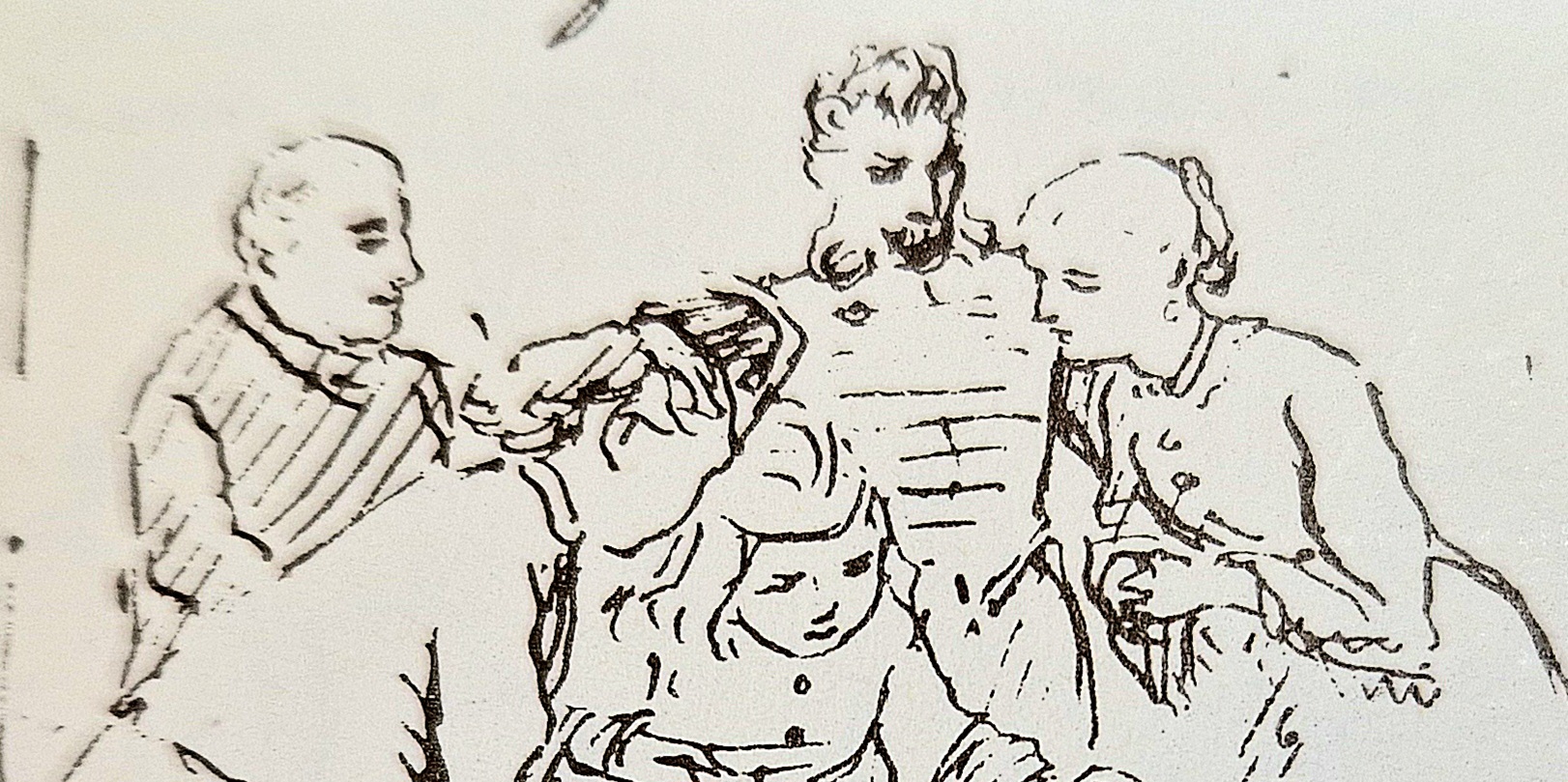

In Berry’s drawing, a tall male stands amongst the group. The lines Berry adds to the jacket are reminiscent of the heavy, horizontal gold braid on the breast of many military uniforms of the period. From Jo Draper’s commentary, this man is likely to be a depiction of Berry and her sister Helen’s host, Major Charles Clapcott.

Draper expands on Major Clapcott’s military career:

“Charles Clapcott became a major in the 23rd (Cornwall) Light Infantry. Hart’s Army List (1872) records: ‘Major Clapcott served … at the 1st and 2nd siege operation before Mooltan, including the attack of the enemy’s position in front of the advanced trenches on 12 Sept 1848, the action of Soorj Koond, storm and capture of the city, and surrender of the fortress. Also present at the surrender of the fort and garrison of Chenicote, and at the battle of Goojerat (Medal with two Clasps)’. All this took place during the second Sikh War of 1848-9, in north-west India” (pg. 48-9).

The “second Sikh War of 1848-9” that Draper is referring to here relates to a war fought between the East India Company and the Sikh Empire. The Sikh Empire was a regional power based in the Punjab region, comprised of modern northwestern India and eastern Pakistan. The Empire existed between 1799 and 1849.

Another set of questions emerge. What was the Second Anglo-Sikh War? What kind of conflict was Major Clapcott involved in?

Prior to the Anglo-Sikh conflicts, the sudden death of Maharaja Ranjit Singh left the Sikh Empire in disarray. A succession of short-lived rulers attempting to fill the power vacuum that Ranjit Singh left behind created political instability. Historian Khushwant Singh neatly summarises the emerging tensions between the Sikh Empire and the neighbouring British-controlled presidencies of “Bengal”, “Bombay”, and “Madras” under the East India Company. With the British fearing that “the state of ‘anarchy’ in the Punjab had come to such a pass that the security of their possessions required the strengthening of the Sutlej frontier” and the Sikhs concluding that the movement of British troops closer to Sikh borders indicated the intention of the British to “take the Punjab as they had taken the rest of India” (pg. 39), the First Anglo-Sikh War began in 1845. After a year of intense fighting and heavy casualties on both sides, the Sikh Empire was defeated following the Battle of Sobraon.

The Treaty of Lahore, ending the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845-6), left the Sikh Empire’s power and independence greatly diminished. Although the young boy Maharaja Duleep Singh was permitted to remain as regent, the installation of a British political agent (a ‘Resident’) effectively granted power to this British representative (Colonel Henry Lawrence) instead. British interference with the Sikh Army’s size, access to weaponry, and autonomy heightened discontent amongst the Sikh soldiers and its leaders. As Khushwant Singh adds, “radical changes introduced in the system of land revenue and its collection angered the landed classes and revenue officials” (pg. 456). He continues: “Vile abuse, maltreatment of natives, and molesting of women by English soldiers became common occurrences”. Resentment towards the British occupation had begun to build, reaching a boiling point.

Beginning in Multan with a revolt against British presence, resistance to British rule spread.

The situation was ideal for several senior members of the East India Company who had become increasingly eager to annex the region. “Lord Dalhousie and his commander-in-chief … agreed with the resident to let the situation deteriorate and then exploit it to their advantage”, highlights Khushwant Singh. As fellow historian Priya Atwal points out, “although a military intervention could be justified under such conditions [like the rebellion], the takeover of Duleep Singh’s entire kingdom could not … since neither the Maharajah nor any of his ministers at Lahore had themselves rebelled” (pg. 203). Instead, the East India Company delayed “deploying the Residency government’s full military powers until the cold weather season, … watch[ing] on as the rebellion worsened into a major conflict, so that a ‘Second Anglo-Sikh War’ and a subsequent annexation could be justified” (pg. 203).

Sher Singh Attariwala, a prominent Sikh military commander, had initially aligned with the British following the Multan revolt. However, he eventually withdrew from the British camp after becoming disillusioned with the Resident’s poor treatment of his father and hearing that the British were mobilising to possibly capture him. Following this, Sher Singh Attariwala issued a public proclamation to the people of Punjab, the Sikhs, and the world, condemning the oppressive rule of the British. Sher Singh’s defection encouraged other Sikh leaders to declare their freedom.

Historian Khushwant Singh highlights the response of Lord Dalhousie (both the Governor-General of India and the Governor of Bengal) to these events as follows: “Lord Dalhousie was pleased with the course of events because it gave him the excuse he was waiting for. ‘The insurrection in Hazara has made great head… I should wish nothing better… I can see no escape from the necessity of annexing this infernal country… I have drawn the sword and this time thrown away the scabbard’” (pg. 76). Lord Dalhousie swiftly declared war, beginning the Second Anglo-Sikh War.

As a member of the British Army, Major Charles Clapcott and his regiment had already been posted to India. As was common in the period, British Army regiments assisted the East India Company’s Army. Draper’s commentary connects Clapcott to major battles in the Second Anglo-Sikh War. The Battle of Gujarat (also known as Gujrat, Gujerat), one of the battles that Clapcott took part in, was decisive for the war’s end. Sir Hugh Gough, the Commander-in-Chief of the British and Company forces “brought 24,000 soldiers to the field to engage a Sikh army 50,000-60,000 in number” according to historian Kaushik Roy (pg. 298). However, the British weaponry had “qualitative and quantitative superiority in artillery over the Sikhs, and the 59 Sikh guns were silenced by 96 British guns”. Roy continues: “Gough won at the cost of 96 killed and 710 wounded. Sikh losses are unknown”.

It was after this battle that Charles Clapcott was given a “Medal with two Clasps”, according to Draper’s notes.

After the surrender of the Sikh army, the 10-year-old Majahara Duleep Singh was compelled to sign an annexation treaty, handing over not only all his dynastic wealth and properties but also the Sikh Empire itself to the East India Company. The treaty also established that the Maharaja surrendered the Koh-i-noor diamond to the British (which now can be seen in the Crown of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother today).

The British victory at the Battle of Gujerat was therefore key in the Punjab region’s annexation to the East India Company’s territories, ending the War and bringing the area under full British control.

Further details, paintings and related images of the battles fought during the Second Anglo-Sikh War can be viewed on the National Army Museum’s website.

Tracing Major Clapcott’s troop has proved slightly difficult. Jo Draper’s notes suggests that he was from “the 23rd (Cornwall) Light Infantry”. However, the National Army Museum suggests the existence of a 32nd “Cornwall light infantry”. This regiment “began its first Indian posting in 1846, remaining there for 13 years. It fought at Multan (1848) and Gujerat (1849) during the Second Sikh War (1848-49)”. The 32nd regiment’s activities align strongly with Major Clapcott’s involvement at “Mooltan” and “Goojerat” as mentioned by Draper. Although a 23rd Cornwall regiment could have existed, our own research can only find a 32nd regiment. Perhaps there is a possibility of a mistake in Draper’s commentary, or do any of our readers know any more?

Draper’s notes do not mention where Clapcott went or what he did following the end of the Second Anglo-Sikh War. She does, however, mention his appointment as Adjutant of the Dorset Militia on the 6th of April 1865. Clapcott’s appointment as Adjutant was seventeen years after his involvement in the War.

From this context, we can see a strong possible source for the name of the dog owned by the Clapcotts. It is likely that Charles Clapcott heard the term “chota” during his post to the Punjab region and in the War that followed.

The Clapcotts’ dog was very likely named “chota” because, like the Punjabi and Hindi definitions, the dog was simply “small”. However, the inspiration or precursor to the dog’s name is associated with a bloody and violent history tied to the wider British colonial project. Through the mentioning of “Chota” the dog, Berry’s diary reveals that the echoes of the British Empire abroad had reached rural Dorset.

At the end of every month, we shall release more content relating to this journal, showcasing the sketches and commentary written by Miss Berry Dallas during her time in Victorian Martinstown.

We look forward to posting the next instalment!

You can find Our Journal at Winterbourn St. Martins in our library at Dorset History Centre under the call mark 942.331 WSM.

References

“32nd (Cornwall Light Infantry) Regiment of Foot”. National Army Museum, https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/32nd-cornwall-light-infantry-regiment-foot.

Atwal, Priya. Royals and Rebels: The Rise and Fall of the Sikh Empire. C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., 2020. Accessed from Oxford Academic, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197548318.003.0006. This book won BBC History Magazine Best Book of 2020.

Dallas, Berry. Our Journal at Winterbourn St. Martins. Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society & Jo Draper, Friary Press, 1982.

Roy, Kaushik. Encyclopedia of the Age of Imperialism, 1800-1914: Volume 1. Edited by Carl Cavanaugh Hodge, Greenwood Press, 2008. Accessed on Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780313334061_1.

Singh, Khushwant. A History of the Sikhs: Volume 2: 1839-2004. 2nd edition, Oxford University Press, 2004. Accessed from Oxford Academic, https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195673098.001.0001.