Since time out of mind in England all land originally derives from the King or Queen. It is therefore not surprising that some of the earliest surviving records in this country are charters recording grants of land by Anglo-Saxon monarchs. Only about two hundred original, authentic Anglo-Saxon charters are believed to survive, although about a thousand are recorded, mostly as later transcripts or summaries. (Source: University of Cambridge)

“The great majority of surviving single-sheet Anglo-Saxon charters are to be found in the British Library, in the collections formed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries by Sir Robert Cotton… and others. A single collection of charters, formed in the eighteenth century, is to be found in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. There are also significant quantities in the archives of Canterbury Cathedral, Westminster Abbey, and Exeter Cathedral. A few others are to be found in local record offices, or still in private hands.” (Source: University of Cambridge.)

For Dorset the earliest surviving reference to a charter is to one of Cenwalh, King of the West Saxons, granting land to the church of Sherborne, around 643-672 AD, although the charter itself is lost (according to Finberg’s Early Charters of Wessex, published 1965.) We know less about Dorset’s charters than those of other neighbouring counties because several monastic cartularies (or collections of charters) have not survived beyond the 19th century.

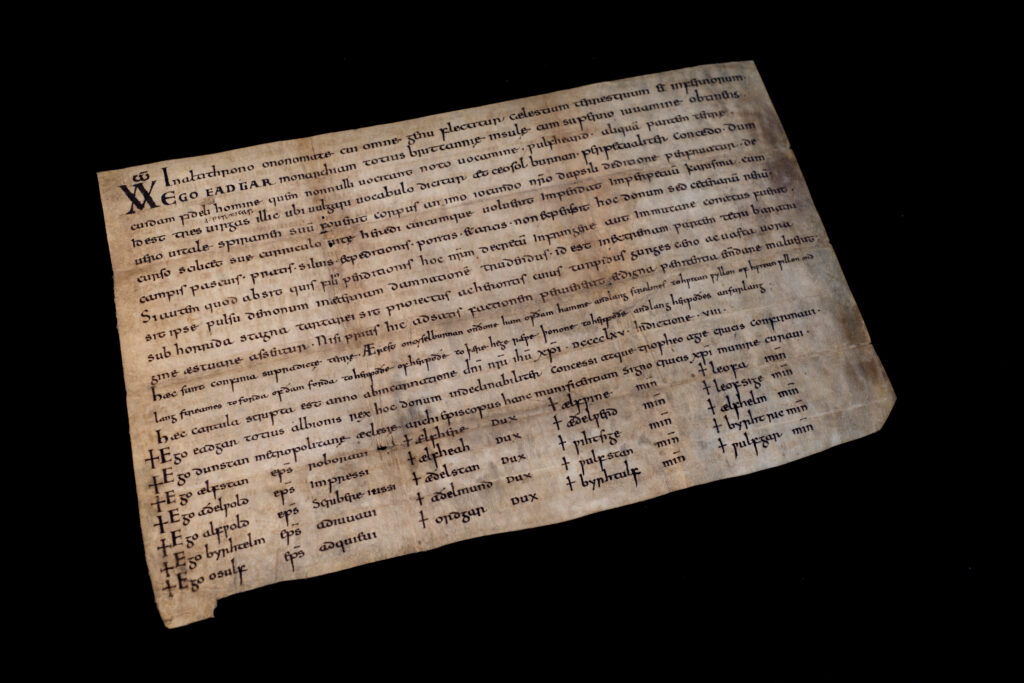

Dorset History Centre is therefore in a very rare and privileged position in holding several documents dating back to the Anglo-Saxon period, including our earliest record, dating from 965 AD.

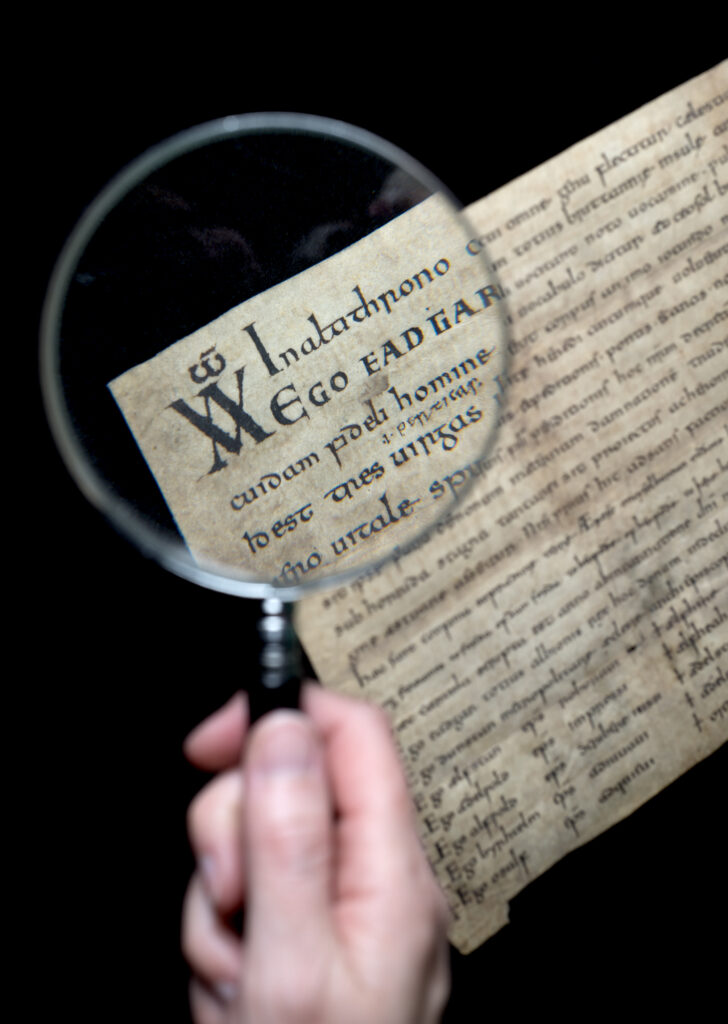

This charter, reference D-FSI/ASC/1, forms part of the Fox-Strangways estate of Ilchester collection. With the growth of Christianity in the Anglo-Saxon period charters often record grants to the church but also to individuals whom the monarch wished to reward for service or loyalty. This is the case with the charter in question – it records a gift of land to a man named Wulfheard, presumably as a reward for some act of loyalty, now unknown, to King Edgar. Edgar lived from 943-975 AD, and his reign was one of comparative peace and prosperity. Edgar was only sixteen when he became King of the West-Saxons, Mercians and Northumbrians in 959 AD but by the end of his reign he was crowned King of the whole of England, including the Danelaw.

The charter D-FSI/ASC/1 is written mostly in Latin, with a small section relating to property boundaries in Anglo-Saxon.

This is a translation:

“In the name of Him who is enthroned on high, to whom every knee bows in heaven, on the earth and in hell.

I EADGAR, obtaining through heavenly aid the monarchy of all the island of Britain, do grant to a certain faithfull man whom some call by the name of Wulfheard a certain piece of land, i.e. three virgates yardlands in a place called in the vulgar tongue “at Ceasol Burnan” (at the gravelly stream) in perpetuity. Whilst he lives he shall enjoy our bountiful gift with a blithe heart. But at the termination of his life the gift shall fall to whichever heir he has chosen for ever, with fields, pastures, meadows, woods, ways, bridges and weirs. But this gift shall not be without other things. If (which may heaven avert) any son of perdition shall try to infringe or change our decree, may he be dragged by the blows of demons into eternal damnation, that is to say, into the furthest part of the foul abyss. May he be hurled under the horrible waters of tartarean Acheron, whose revolting stream is said to seethe with filth and a great whirlpool. Unless he shall have made satisfaction here and chosen to amend with worthy repentance.

These are the bounds of the aforesaid land: first to Cyselburnan [Cheselbourne] to the enclosure, from the enclosure along stream to White Spring, from White Spring along stream to the ford, from the ford to the highway, from the highway, to the row of trees, then to the highway, along the highway for one furlong.

This charter was written in the year from the birth of Our Lord Jesus Christ DCCCCLXV (965) [and in the] VIII (8th) year of the Indiction.

+ I Eadgar King of all England, have unchangeably granted this gift and confirmed [it] with the sign of the Holy Cross

+ I Dunstan, Archbishop of the Metropolitan Church, have taken care to strengthen this bountiful gift with the sign of the Cross of Christ.

+ I Athelwold, Bishop, have confirmed it.

+ I Alfwold, Bishop, have ordered it to be written.

+ I Byrhthelm, Bishop, have assisted.

+ I Osulf, Bishop, have agreed.

+ Aelfhere Ealdorman

+ Aelfheah Ealdorman

+ Aethelstan Ealdorman

+ Athelmund Ealdorman

+ Ordgar Ealdorman

+ Aelfwine Min[ister.]

+ Aethelwerd Min[ister.]

+ Wihtsige Min[ister.]

+ Wulfstan Min[ister.]

+ Byrhtulf Min[ister.]

+ Leofa Min[ister.]

+ Leofsige Min[ister.]

+ Aelfhelm Min[ister.]

+ Byrhtric Min[ister.]

+ Wulfgar Min[ister.]”

Endorsed: This is the charter of the three virgates at Ceosol burnan [Cheselbourne] which King Eadgar has granted to Wulfheard in perpetuity.

Several things really stand out about this document and invite further research to help with their interpretation.

First, the relatively small amount of land involved. Three virgates is about ninety acres of land. A virgate is the amount of land that a team of two oxen could plough in a single annual season, nominally thirty acres. The charter contains a huge number of prestigious witnesses for such a small area of land. The witnesses include the King, his chief advisor the Archbishop of Canterbury, four other bishops, five earldormen (chief officers in charge of a district such as a shire), and ten ministers (church leaders.) However, this is where it is important to understand the context. The King would be presented with a series of charters to confirm at a royal assembly. The list of witnesses are in effect a list of attendees at one of these assemblies. The grant to Wulfheard would have been just one piece of business dealt with at the assembly.

Secondly, the site of the grant. This is shrouded in mystery because of the generic description of the land. The Proceedings of Dorset Natural History and Archaeology Society Vol 66 pp129-130 (published 1934) states “as in the case of many such small grants, its actual site can be no more than a matter of conjecture.”

The “only definite indication of the site of the grant is that it is on the Cheselbourne, the stream which flows through Cheselbourne Village and enters the Devil’s Brook near the south end of Dewlish park.”

Cheselbourne is a village seven miles north east of Dorchester. According to the Domesday book, written just a hundred and twenty-one years after the charter in question, there were thirty six people there (twenty one villagers, ten smallholders and five slaves) and the chief landowner was Shaftesbury Abbey, although it was in the hands of the monarch still at the time of the Conquest.

Last but not least, a modern audience is fascinated by the ornate references to heaven and hell and curses to anyone disobeying the charter’s conditions. Research shows that such curses are very common in Anglo-Saxon charters – see research by Petra Hoffman for example. Her work interestingly reveals that the use of Classical references to hell such as “Tartarean Acheron” (language from Greek mythology for a river running through an abyss) rather than biblical language is at its peak at the time D-FSI/ASC/1 was written. Dorset’s charter, in effect, was also a way for the scribe to show off their Classical education!

This document is a brief glimpse into a lost world – very close in time to the world of TV’s The Last Kingdom. Wulfheard of Cheselbourne was once a living, breathing person, perhaps with a family, friends, and certainly with a loyal relationship to King Edgar. We may never know much more about his world but it might make Wulfheard’s heart “blithe” indeed to think he lives on in this precious and unique archive, kept in the best of conditions at Dorset History Centre.

Another logical place to search for evidence of Anglo-Saxons in Dorset is, of course, the Historic Environment Record. This was searched for Cheselbourne but without any success in finding archaeology relating to Wulfheard. Please see: https://heritage.dorsetcouncil.gov.uk/guidance in order to search the HER.

If you have been inspired to view this archive, the original is not normally produced to protect it from deterioration, except in exceptional circumstances such as a recent From the Stacks talk. However, a high quality facsimile can now be seen on the wall of our searchroom, and it is also viewable in digital form.