The Bankes collection is a remarkable assortment of records covering all sorts of time periods and subject matters. There are antiquarian records, there are estate records, there are examples of account books, farm records, or personal papers. The oldest thing in this collection dates from 1249, and the collection runs through until the 1980s.

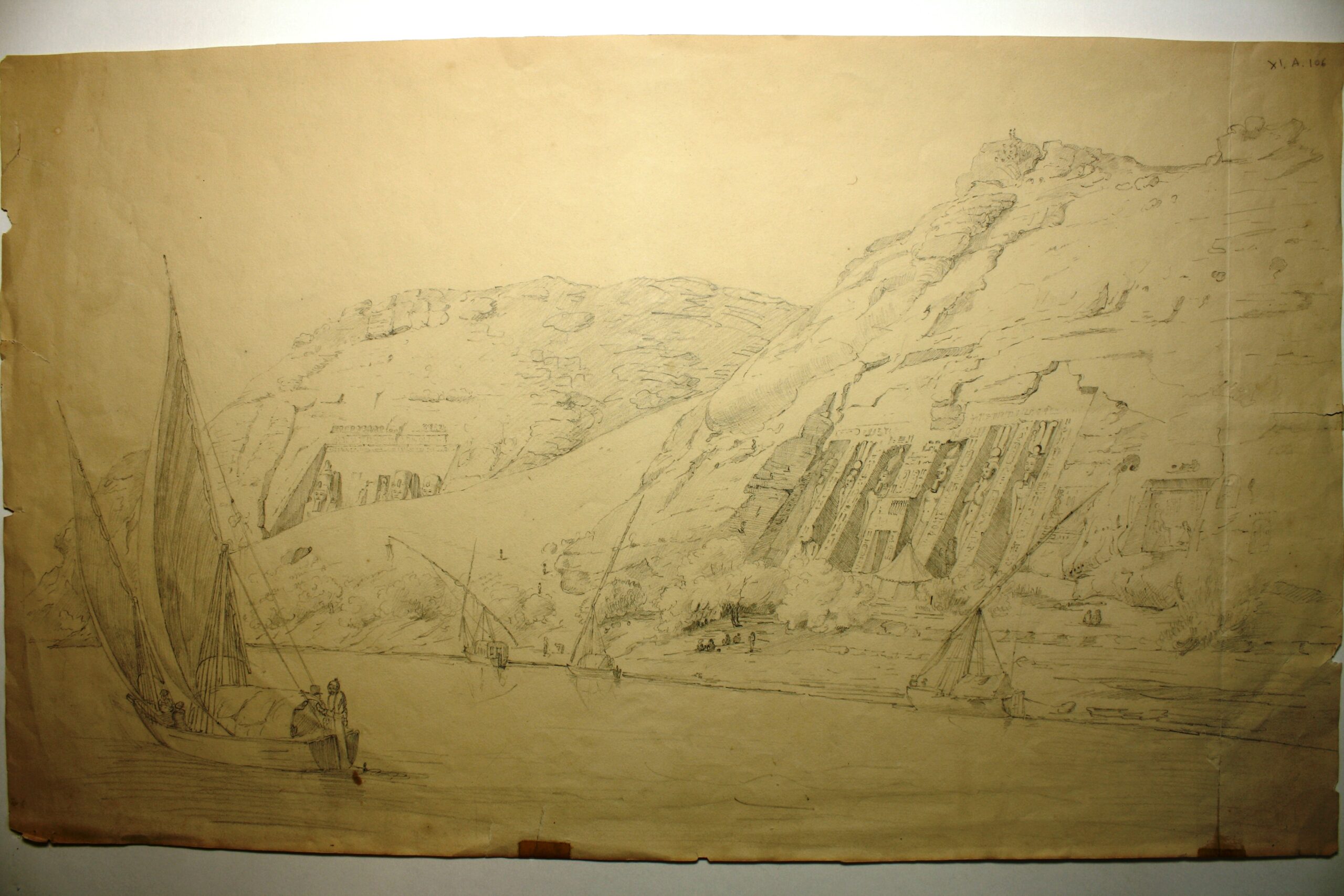

In amongst this collection there are over 2,700 drawings from Egypt and the Middle east, drawn in the period between 1815 and 1825 by William John Bankes and his travelling companions. These drawings represent a part of history which in many cases has now been destroyed, either by war, time, or industrial progress. As such, detailed images of how these places looked in the early 19th Century, at a time when Egyptology was taking off in Europe as a discipline, are remarkable in their scope and what can be learned from them.

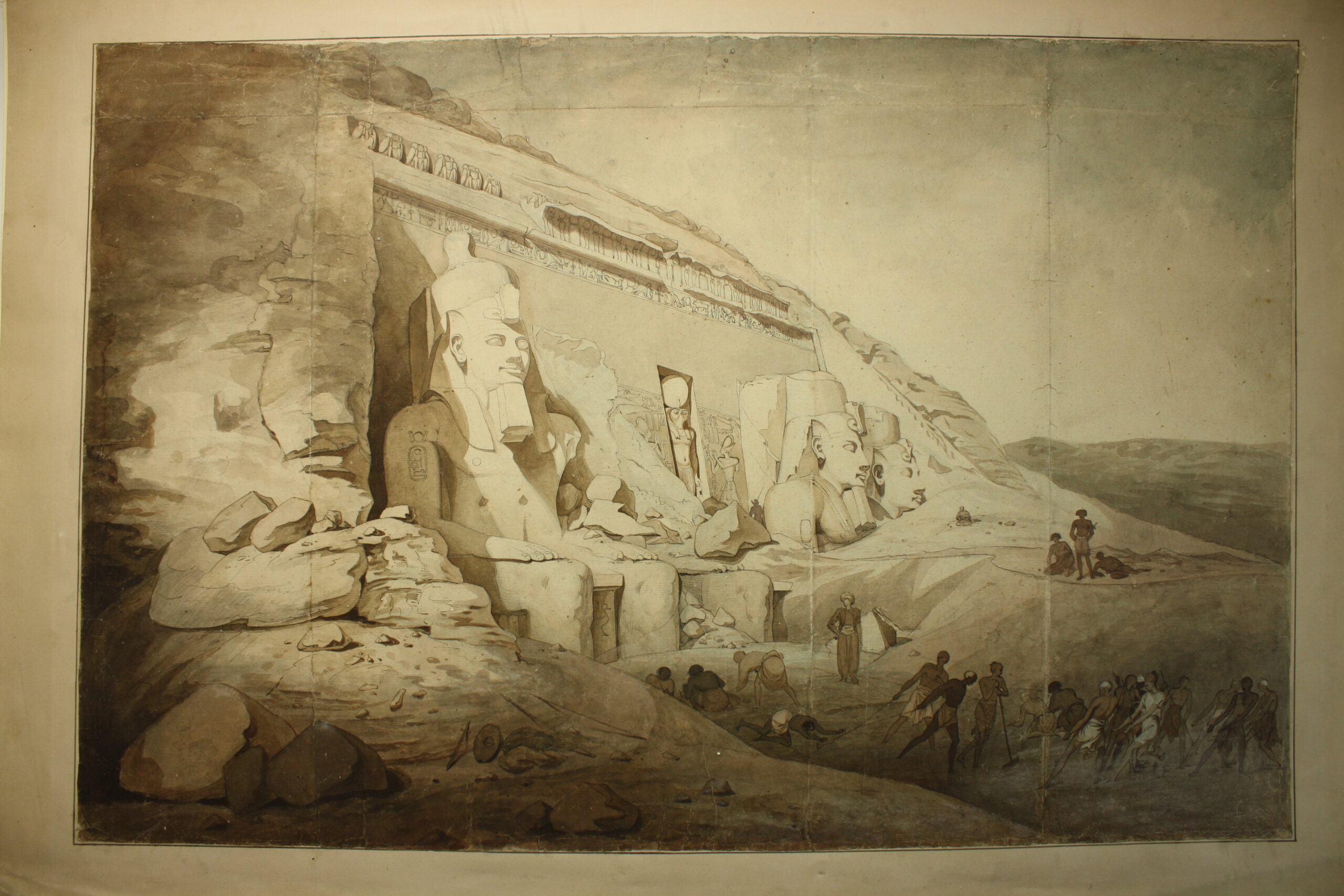

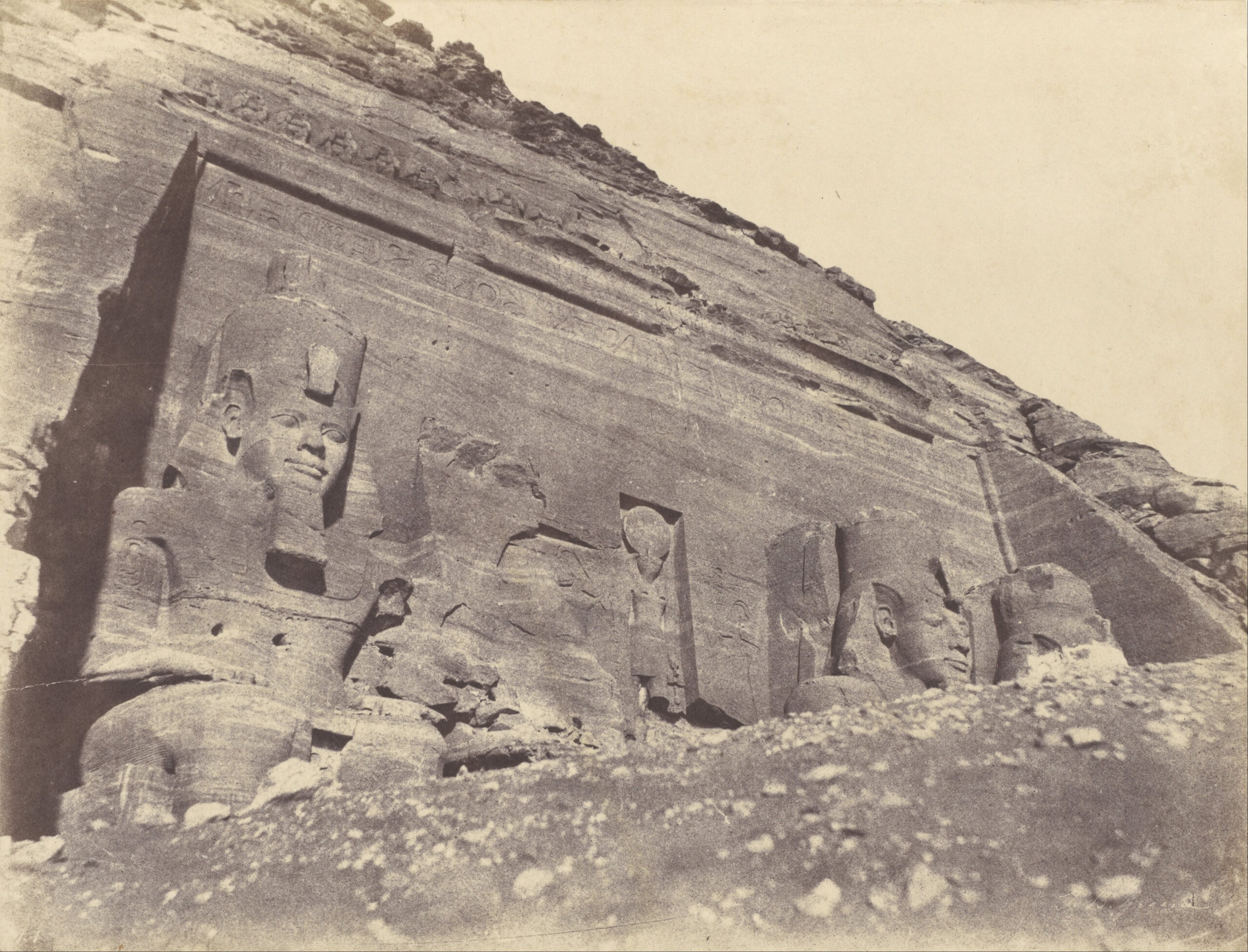

These drawings also show us something of the herculean efforts sometimes required to make sites visible again, with the most notable of these are the drawings of the famous temple at Abu Simbel. Now the site is a major tourist destination, with hundreds of thousands of visitors each year, however when Bankes and his party arrived at the site in 1819 things were quite different. The site was buried under sand, with only bits of the enormous sculpture visible. This was the same as it had been when Johann Burckhardt first saw the site in 1813 too, and he had been unable to find a way into the complex through the sheer volume of sand.

Patricia Usick helpfully explains the chronology of the site at this time:

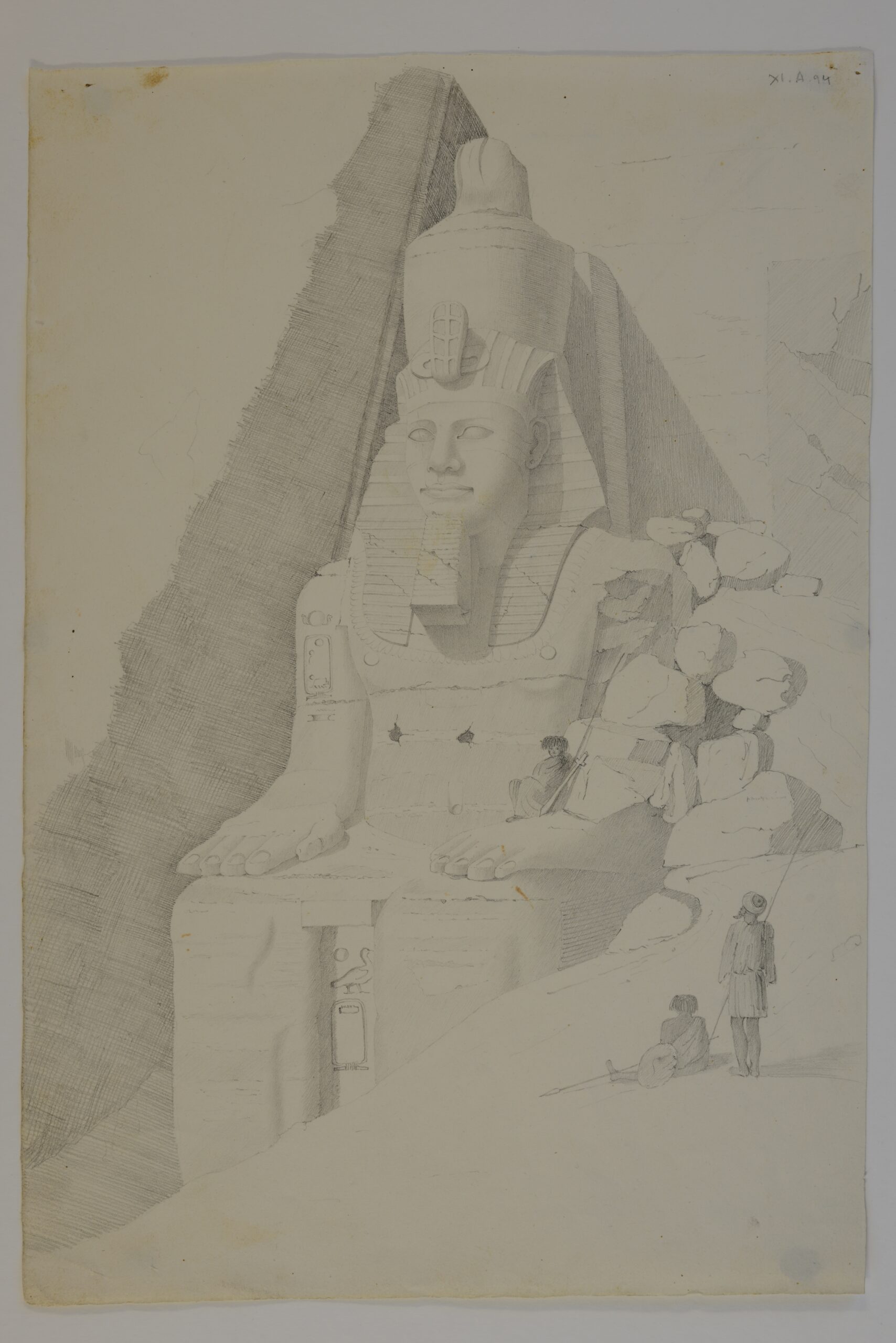

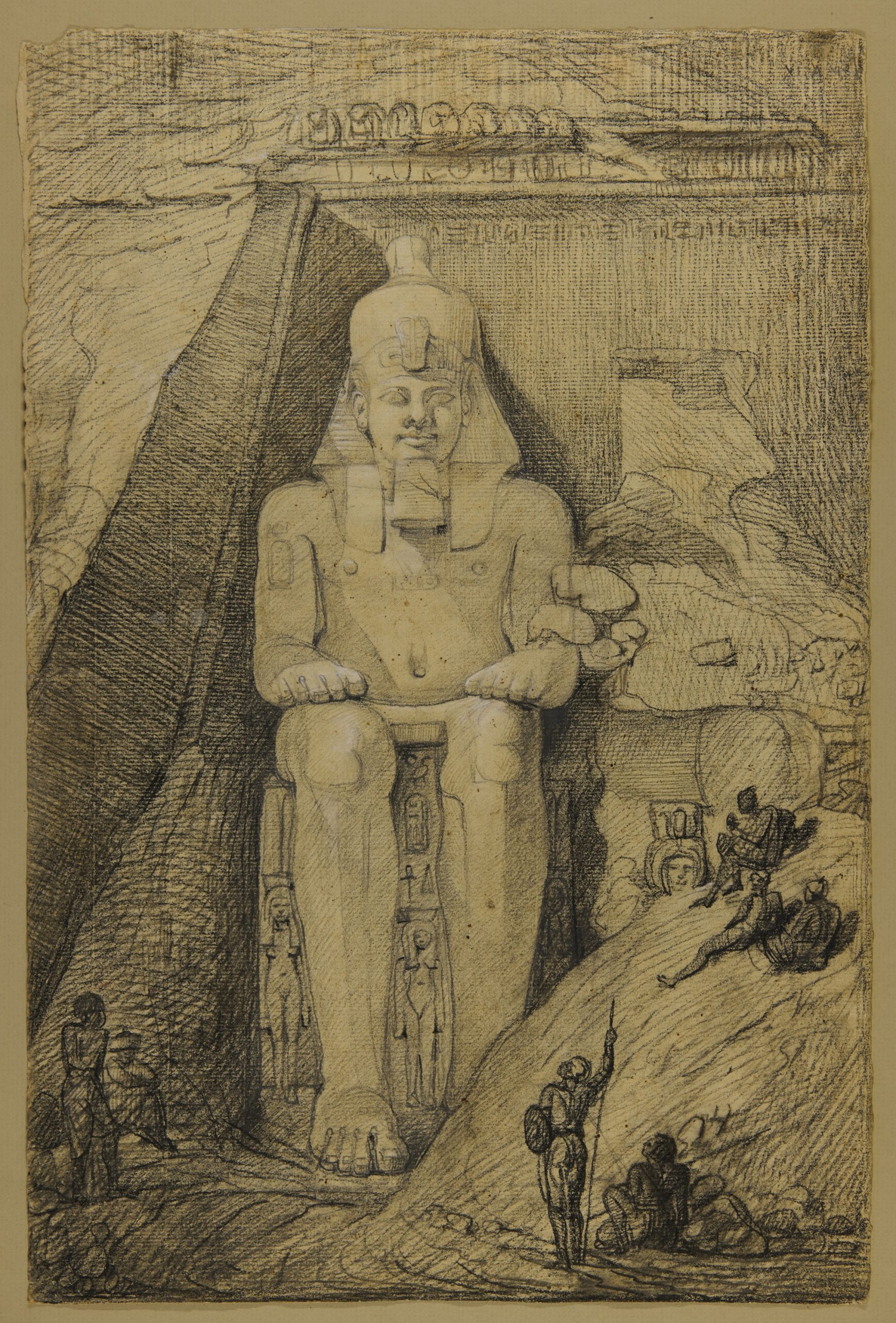

The Great Temple (first stumbled upon unexpectedly by Burckhardt in March 1813, sketched by Bankes in 1815, and opened by [Giovanni] Belzoni only in 1817) inspired Bankes to excavate one of the colossal figures down to the feet, having speculated in 1815 that the four great seated colossi, of which only the heads were visible under the great sand-drift, might be standing. It took them fourteen days of working with thirty hands to uncover the first figure. Despite Bankes’s initial opinion that the sand could easily be carried to the Nile and thrown in, this method proved unworkable, and it was possible to uncover the façade only a section at a time.

Adventures in Egypt and Nubia: The Travels of William John Bankes (1786-1855), P. Usick, 2002, p.118

Usick spent a lot of time working with the Bankes Egyptian drawings whilst they were located at the British Museum in the 1990s, and her study dates this excavation work to between 24 January and 17 February 1819.

The drawings in the collection detail the process that was undertaken to dig-out the complex from the desert, and show us a fascinating process of the work over a period of just a few weeks…

Interestingly, despite this work by Bankes’ team, the earliest known photograph of the site, taken by John Beesley Green in 1854, clearly shows that some of the sand had returned:

More information about Bankes’ travels and the sites he saw in Egypt can be found in Usick’s very useful book “Adventures in Egypt and Nubia: The Travels of William John Bankes (1786-1855)“, 2002.