Between 2015 and 2018 Dorset History Centre undertook the ‘Unlocking the Bankes archive‘ project. During the life of this project, staff and volunteers contributed well over 100 blogs to the project website. By 2024, this project website was no longer functional in the way it originally was, and we made the decision to close the website permanently.

However, we didn’t want to lose all of the intriguing stories and individual research which had been done by so many people, and we are therefore going to slowly be recycling these pieces onto this blog site going forward, to ensure that these fascinating tales have a home for people to read (or possibly re-read)!

This time we take a look at how Frances Bankes looked after her family’s health…

—

Frances Bankes (1760-1823), mistress of Kingston Lacy and mother to six children, took her family’s health seriously. In her meticulous medical notebook, she left a fascinating account of a procedure that still causes controversy today – inoculation.

Smallpox was one of the most feared diseases of the age. In it’s worst form smallpox killed 20% of sufferers, and left many survivors horribly disfigured. The eastern practice of inoculation was introduced to Britain in 1721 by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the Turkish ambassadress, and by the time Frances’ and Henry’s children were born it was well established, even fashionable, amongst those who could afford the treatment.

Inoculation vs. Vaccination – what’s the difference?

Inoculation, or variolation, is the injection of the smallpox virus into the patient – in effect inducing a mild bout of smallpox. The virus would be taken from the scabs or pustules of a smallpox sufferer, and is a practice likely as old as the disease itself.

Vaccination is the injection of the safer cowpox virus, which, following a bout of cowpox, gives the patient immunity to smallpox. The word is derived from the latin ‘vacca’ meaning ‘cow’. Reports of this gentler method are known to have circulated in southwest England from the 1770s. Benjamin Jesty, a farmer from west Dorset who later lived in Purbeck, claimed to have inoculated his wife with cowpox in 1774.

It is possible that Henry and Frances Bankes knew of this procedure: their local physician, Dr Richard Pulteney of Blandford, gave evidence to the House of Commons Committee in 1802 that granted Edward Jenner’s ‘reward’ for the discovery. However, vaccination was not accepted practice when their children were young.

Inoculation and the Bankes

The three eldest boys were given the standard ‘variolation’. It was an unpleasant and risky procedure to subject a small baby to: a death rate of 1 in 200 even in the best hands; 2 or 3 weeks of distressing symptoms; potential scarring; and a risk of infecting those around them.

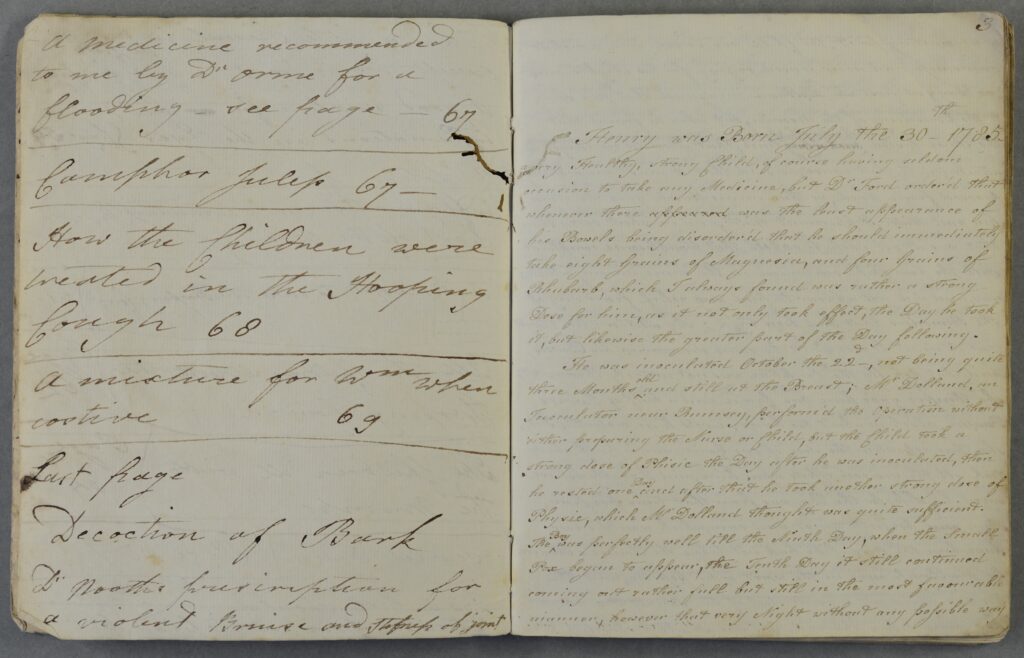

In her notebook (D-BKL/H/I/1), Frances recorded a day-by-day account of the treatment, and pinned the doctors’ prescriptions to the relevant pages. Anyone who has sat up with a fretful baby after a vaccination, with a bottle of Calpol to hand, can perhaps sympathise with Frances’s anxiety.

The inoculation of Henry Bankes

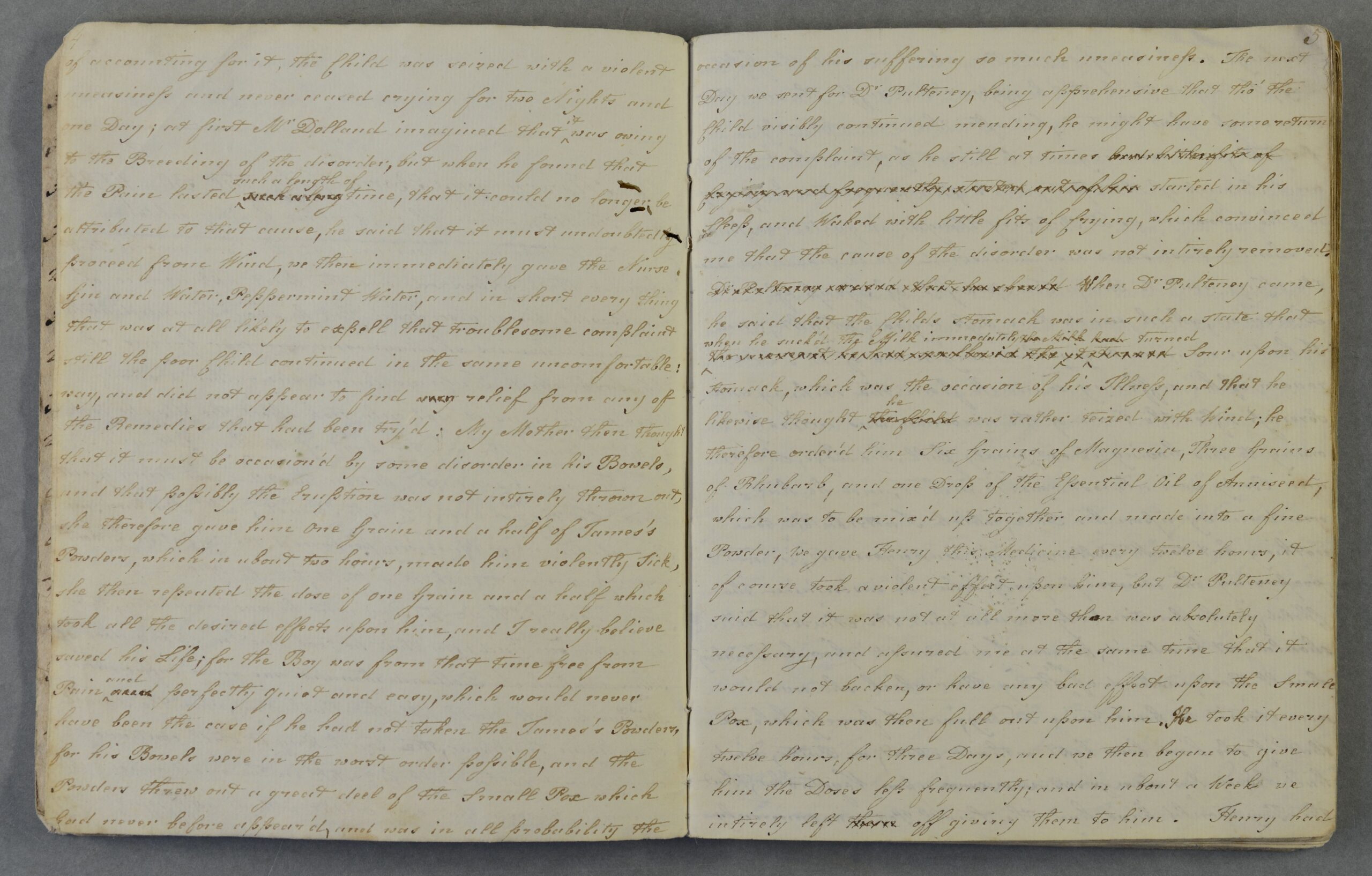

Frances’ first child, Henry, was born on the 30th July 1785, and appears to have been inoculated in Kingston Lacy:

‘a very healthy Strong Child……He was inoculated October the 22nd – not being quite three Months old, and still at the breast.’

It seems that Henry had a fortunate start to his inoculation, until the infection began to show on the ninth day:

‘that very night the Child was seized with a violent uneasiness and never ceased crying for two nights and one Day’

Mr Dolland, the ‘inoculator’, recommended James’s powders, a patented fever remedy containing antimony and phosphate of lime. Frances was not happy and sent for Dr Pulteney, who attributed his symptoms to wind:

‘…he therefore order’d him Six Grains of Magnesia, three Grains of Rhubarb, and one Drop of the Essential Oil of Anniseed, made up into a fine Powder….it of course had a violent effect upon him, but Dr Pulteney said that it was not more than was absolutely necessary’

It was the doctors’ aim for the patient to have the disease as mildly as possible, by injecting ‘matter’ from someone with less virulent disease and preparing the patient (and wet nurse if breast-fed) beforehand with diets and purges. It appears Henry was unlucky, and Frances had some strong opinions as to the case:

‘Henry had the large broad sort of Small Pox…his Legs, Arms and Body were almost entirely cover’d with it, he had a great many upon his face, which I attributed to nothing but Mr Dolland’s mismanagement, in not preparing the Nurse properly’

‘I firmly believe that if she had been kept without Meat or Butter, and had lived low upon Vegetables, that the Boy would have had the Small Pox uncommonly well; but as it was I did not approve of Mr Dolland’s method by any means’

The inoculation of William John Bankes

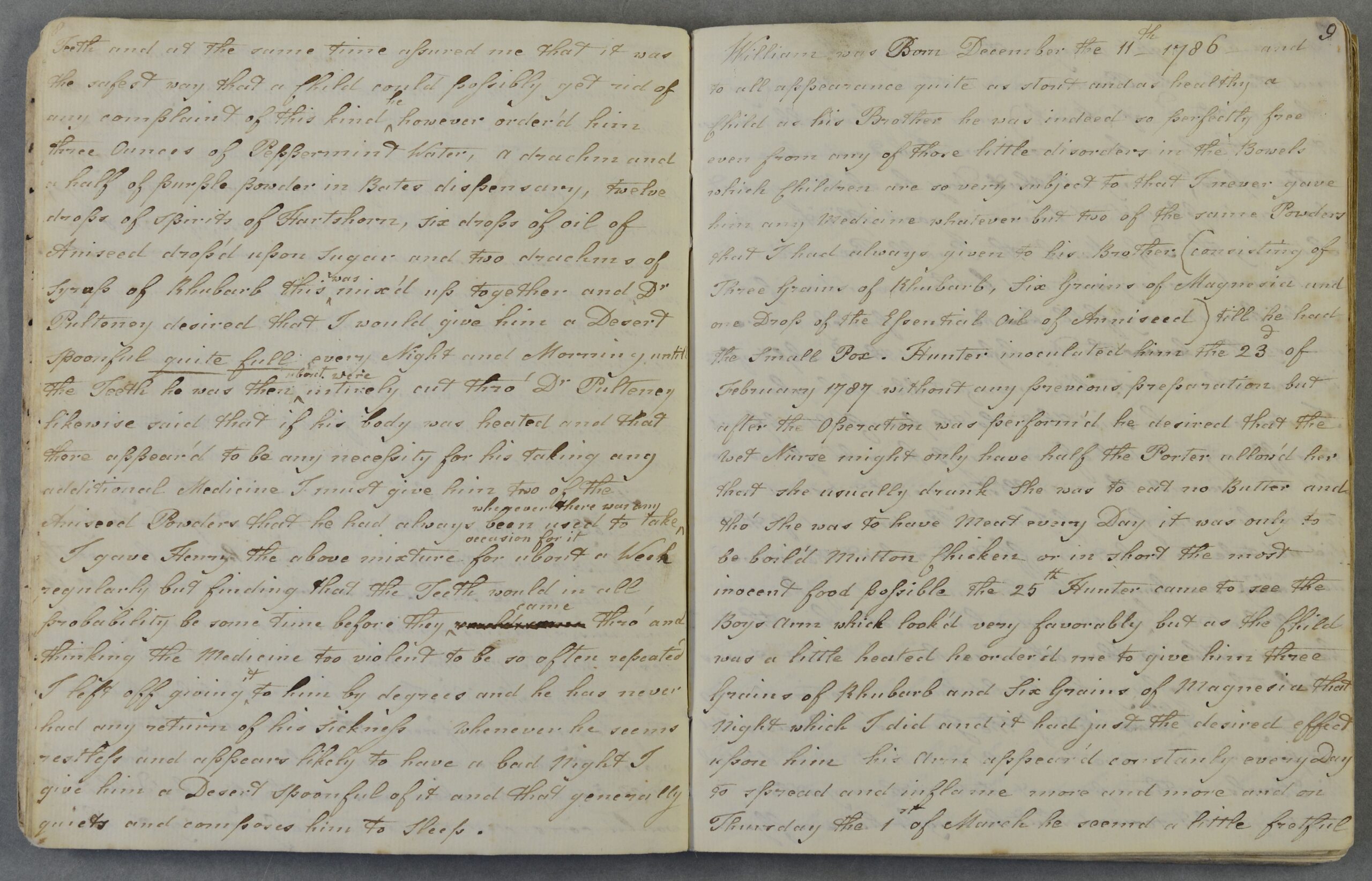

Frances’ second son, William John, appears to have been inoculated at around two and a half months old, this time in London. She engaged the famous surgeon John Hunter and the Prince Regent’s physician Dr Robert Hallifax to oversee the treatment.

‘Hunter inoculated him on 23rd February 1787 without any previous preparation but….he desired that the wet Nurse might only have half the Porter allow’d her. She was to eat no Butter …….. in short the most inocent food possible’

Hunter visited two days later to check the boy’s arm, and things seemed to be going well. Frances remarks that ‘he had not above twelve spots’. But as the smallpox came out William became uneasy, and Mr Hunter resorted to the usual treatment of trying to stimulate the bowels:

‘…he said it was absolutely necessary he should have a motion during the Day and told me that if the James’s powders did not procure him one he… desired that he might have a Clyster made of warm water’ (a clyster was an small rectal enema, administered by a bulb syringe).

Frances followed the doctor’s orders and gave William his dose.

‘in less than an hour it made him violently Sick he vomited four or five different times and brought up a great quantity of bile’.

Unfortunately this seemed to have had little effect on William’s condition:

‘when I call’d in the Nursery on my way to Bed I found that he had a great deal of Fever and was quite as ill as ever again… about eight o’clock in the morning they brought me word that he had just had a motion but that the Nurse really thought him worse than he had ever been yet; this account alarm’d me very much’

Frances again called for a second opinion, and sent for Dr Hallifax. His treatment consisted of clysters, and composing draughts for both William and his wet nurse, the latter of which had a violent reaction to the treatment. Both doctors now visited twice daily, and by the 7th March, 12 days after the initial inoculation,

‘they found the Pock risen very much since the night before and Hallifax assur’d me that he thought the Boy now entirely out of danger’.

Harsh consequences

The notebook continues to describe other ailments suffered by the children, but there is no mention of inoculation for the younger ones (Anne, Maria and Edward). Frances by then must have had more experience than most in nursing inoculated babies – but it is thought (no direct records survive) her youngest child Frederick, born in 1799, died a few weeks after being inoculated, a reminder of the dangers of both the disease and the treatment.

It was not only the wealthy like the Bankes family who were being inoculated against smallpox at this time. Our transcription of the Milton Abbas Overseers of the Poor Accounts reveals that, in the face of outbreaks of the disease in the 1770s and 1790s, the overseers paid for the inoculation of large numbers of parishioners by probably the same local inoculator used by Frances Bankes for her son Henry. The entry in the Accounts for August 1776 reads “the inhabitants of Milton Abbas that was inoculated by Dr Dolling was Three Hundred and fifty six.” This was at the cost of 5s and 3d a head, making the remarkable total of £36 15s. With other expenses, the parish spent nearly a quarter of its income in 1776 on alleviating the impact of the disease. When smallpox returned in 1795, 95 people were inoculated at a cost of £21 7s 6d. After that date, there are no specific mentions of smallpox or inoculation in the accounts, suggesting the practice may have ceased in the parish. Dr. John Dolling, probably the “Mr. Dolland” of the Bankes diary, advertised in the Salisbury and Wiltshire Journal from the 1760s to the 1790s, offering to inoculate individual patients, at his house or their own, but also to inoculate whole parishes.