New accessions arrive at Dorset History Centre almost every week, each one bringing its own story – and sometimes its own challenges. Before anything enters our climate‑controlled repositories, it’s assessed by our Collections Archivist, listed, boxed, and prepared for long‑term storage. But some items need an extra stop along the way: the conservation studio.

The biggest risks we encounter in new accessions are mould and pests. Both can spread quickly and cause serious, sometimes irreversible, damage. When that happens, our Conservator steps in to stabilise the material and make sure it’s safe to join the rest of the collection. Recently, several accessions have put our conservation processes, and PPE supplies, to the test.

A Fire, Months of Damp, and a Mountain of Mould

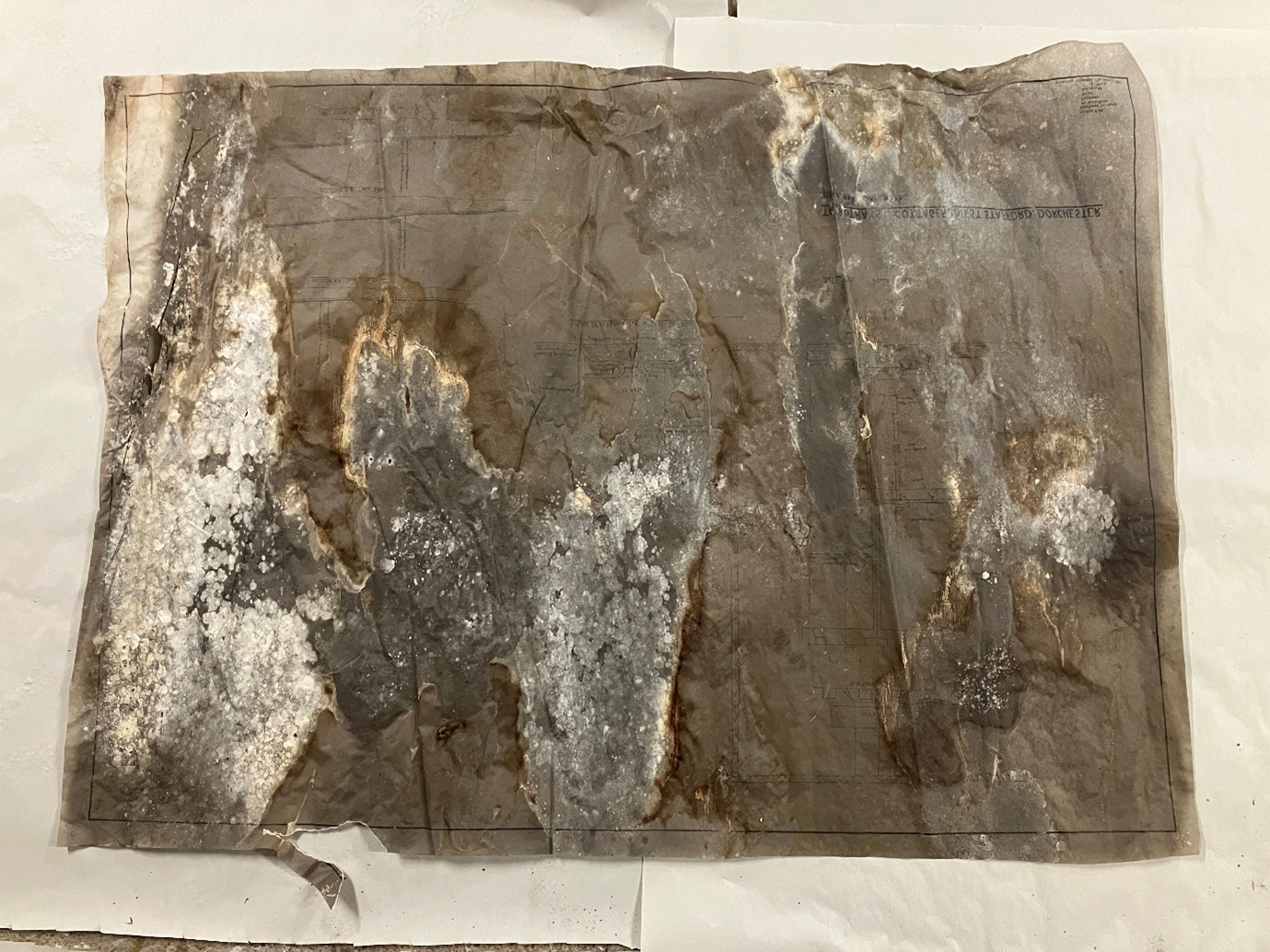

One of the most challenging accessions we’ve seen in recent years arrived after a building fire at the end of 2024. A large collection of architectural plans and documents had survived the blaze and the firefighting efforts, only to be left wet and unprotected for months afterwards.

When the material reached us in 2025, it included piles of large maps and plans and six bin bags of documents, all damp and visibly mouldy. Mould attacks the cellulose structure of paper, causing weakness, distortion, staining, and in some cases total loss. Because mould spores spread easily through the air, none of this material could safely enter our repositories.

The entire collection was placed in quarantine and assessed by our Conservator. Before any treatment could begin, everything had to be dried to stop further damage and allow for treatment. Items were laid out on blotting paper and left to air dry—a slow and space‑hungry process. Once dry, the items returned to quarantine. Although the mould was no longer active, specialist cleaning was still required before anything could be considered safe for storage. With such a large volume of material, this work is ongoing, and we’re still waiting to discover what stories these documents might hold.

Parchment Deeds from a Damp Basement

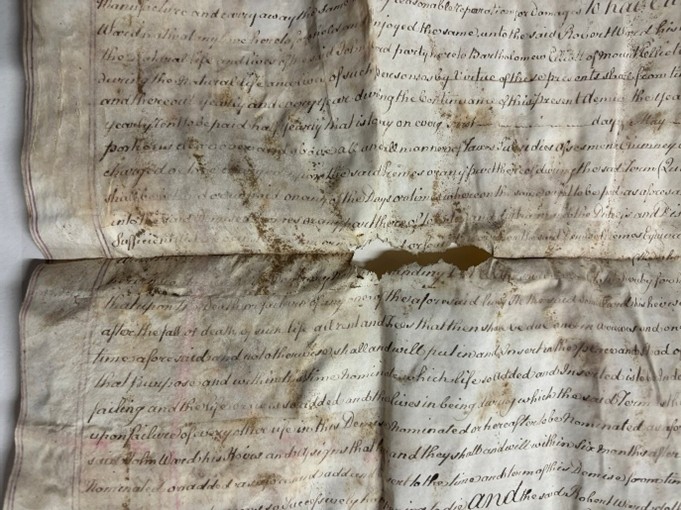

Another accession last year consisted of a large group of parchment deeds that had been stored in a damp basement. They arrived with mould, water damage, distortion, and in some cases areas of loss. Some documents had stuck together and had to be gently separated; others showed staining, weakened parchment fibres and damage to the ink.

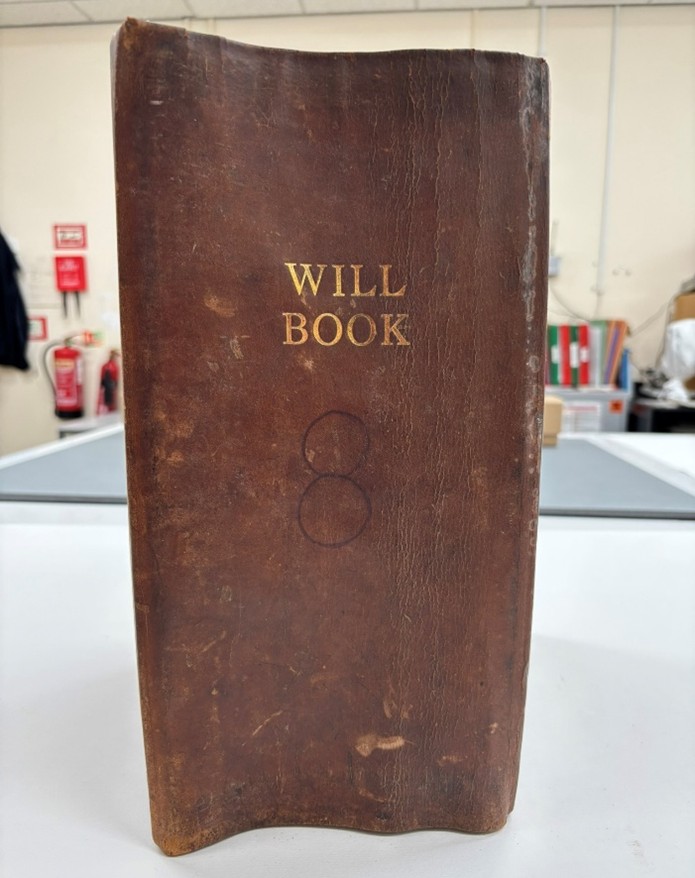

Among them was a particularly large volume heavily affected by mould. It was stood upright on blotting paper with its pages fanned open to dry. Once dry, mould deposits were removed using a soft brush and a conservation vacuum fitted with a HEPA filter. The volume then moved to the conservation studio for further cleaning under fume extraction.

Spotting the Subtle Signs

Not all damage is immediately obvious. Sometimes the clues are small: slight cockling along the edges of a book, suggesting high humidity, or tiny holes that hint at insect activity. A gentle tap on a table may release tiny black particles – frass, the waste left behind by insects – confirming the presence of pests.

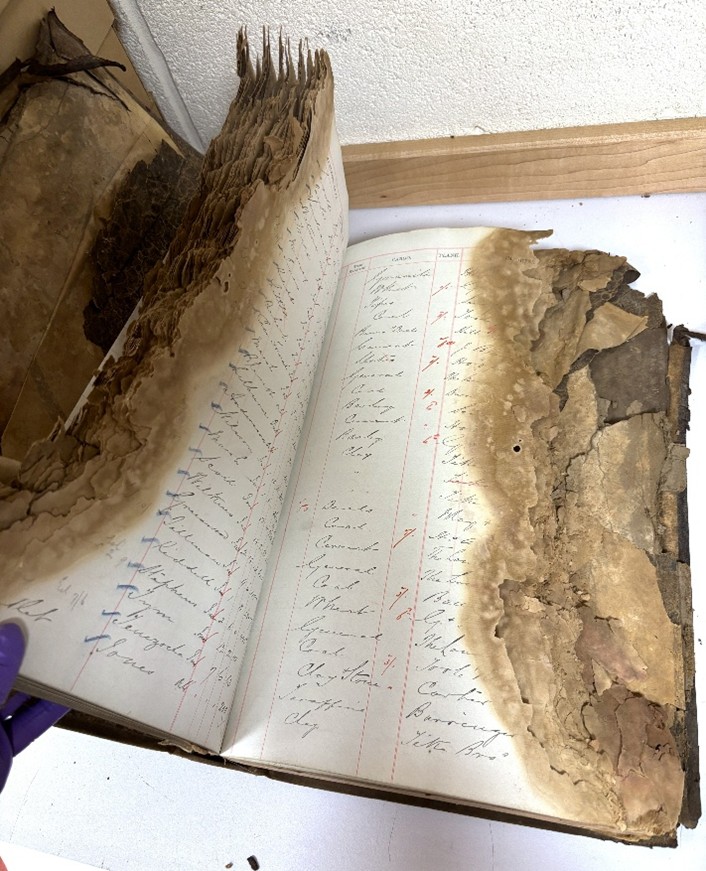

Other times, the damage is unmistakable. A recent accession included several volumes so deteriorated that no investigation was needed to see the extent of the problem. At present, the conservation work required is beyond our capacity, meaning these items remain inaccessible. Preventing records from reaching this stage is one of the strongest arguments for depositing them with us sooner rather than later.

Why Early Deposit Matters

Mould and pest damage can be time‑consuming, costly, and sometimes impossible to reverse. By the time some collections reach us, the deterioration is already severe. Storing records at DHC gives them the best chance of long‑term survival, ensuring they remain accessible for researchers, communities, and future generations.

Every new accession tells a story, but it’s our job to make sure the physical record survives long enough for that story to be told.