Following on from our series of blogs on the Extra-illustrated Edition of Rev. John Hutchins’ ‘The History and Antiquities of the County of Dorset’ we have been looking in more detail at the author and the troubled history of his book.

—

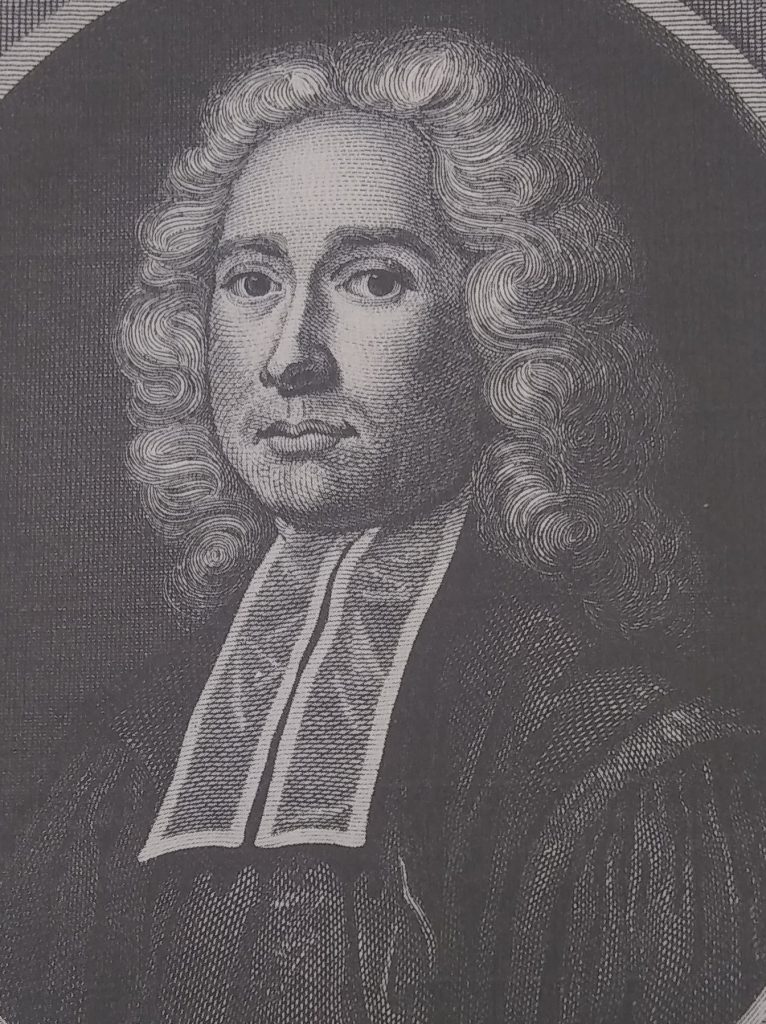

John Hutchins was born on 21st September 1698 in Bradford Peverell. He was the son of Richard Hutchins and his wife Anne, who died when John was 8. Hutchins attended Dorchester Grammar School where he was encouraged in his studies by his schoolmaster, Rev. William Thornton, a man he came to view as a second parent.

Hutchins continued his academic studies at Oxford and Cambridge. The four years he spent at these universities seem to be the only time in his life that he lived outside of Dorset. On conclusion of his studies he was ordained and was appointed curate to the Vicar of Milton Abbas in 1723. It was here that Hutchins began researching his book, supported and encouraged by the noted historian and antiquary Browne Willis and his patron Jacob Bancks, owner of Milton Abbas. In his book Hutchins writes a glowing description of Jacob Bancks, who died suddenly in 1737. He says,

“Jacob Bancks was a most accomplished and well-bred gentleman, his person graceful, his presence noble, his deportment and address engaging, polite affable and humane. He had a natural vivacity of spirit, and a peculiar sweetness of temper; and he studied to be agreeable, without lessening his dignity. He was a true lover of his country, a firm friend to the constitution in church and state, and extremely popular in this county, in which, his interest and reputation exceeded that of those who were his superiors only in point of fortune.”

He continues to express his pleasure in having known and been friends with Jacob and finishes by bemoaning the fact that his ‘heir and relation erected no monument, nor charged the stone that covers him with the least inscription, to point out to posterity where the remains of so worthy a man are deposited.’

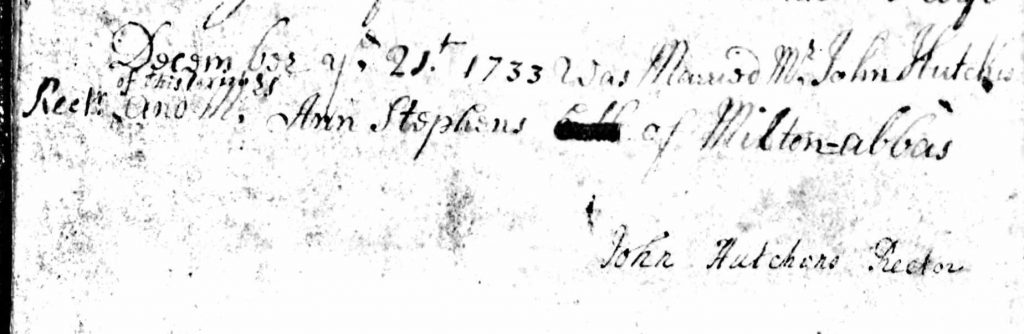

Hutchins was appointed vicar of Swyre in 1729 and to Melcombe Horsey in 1733, where he married Ann Stephens, daughter of the Reverend Thomas Stephens. They had one daughter, Anne Martha.

In 1744 he became rector of Wareham, which was a hindrance to his progress on his book. The town was much larger than either of his other two parishes and therefore demanded much more of his time. Almost half the town were non-conformists and if the congregation was neglected there was always a chance of them changing their allegiance.

Hutchins does not appear to be a man well suited to the task of inspiring his parishioners. He was intelligent and conscientious, but does not appear to have been a great speaker. Even his friend G. Bingham, in his biographical anecdotes, writes;

“In his clerical capacity he deserved the character of a sound Divine rather than of an eminent preacher.”

His parishioners complained of being unable to hear him, especially as his voice, which had never been strong, became weakened by age.

Despite the lack of time available to him Hutchins persisted with his work, mainly relying on the correspondence of his friends and assistants to obtain the information that he needed. It was however, occasionally necessary for him to leave the town to view manuscripts and in order to allow him to leave town he had to appoint a curate to complete his duties for him. It is suggested in his biographical notes that he was forced to appoint a curate in haste, but that there was no reason for him to suspect the man he appointed would cause him quite so many problems.

We have been unable to find the name of this curate, but apparently he was a great orator and very quickly won the regard of the congregation. Hutchins, however, was alarmed by his views, which he believed to be Methodist. Hutchins was wise enough not to immediately dismiss the man, who had become very popular, and was forced to put up with him until he was discovered to be mad and sent to an asylum.

More trouble followed with the fire at Wareham, which destroyed many of his notes and it was fortunate that his manuscript was saved. By this time Hutchins was elderly and suffering from gout and it must have taken a great deal of perseverance to finish his work.

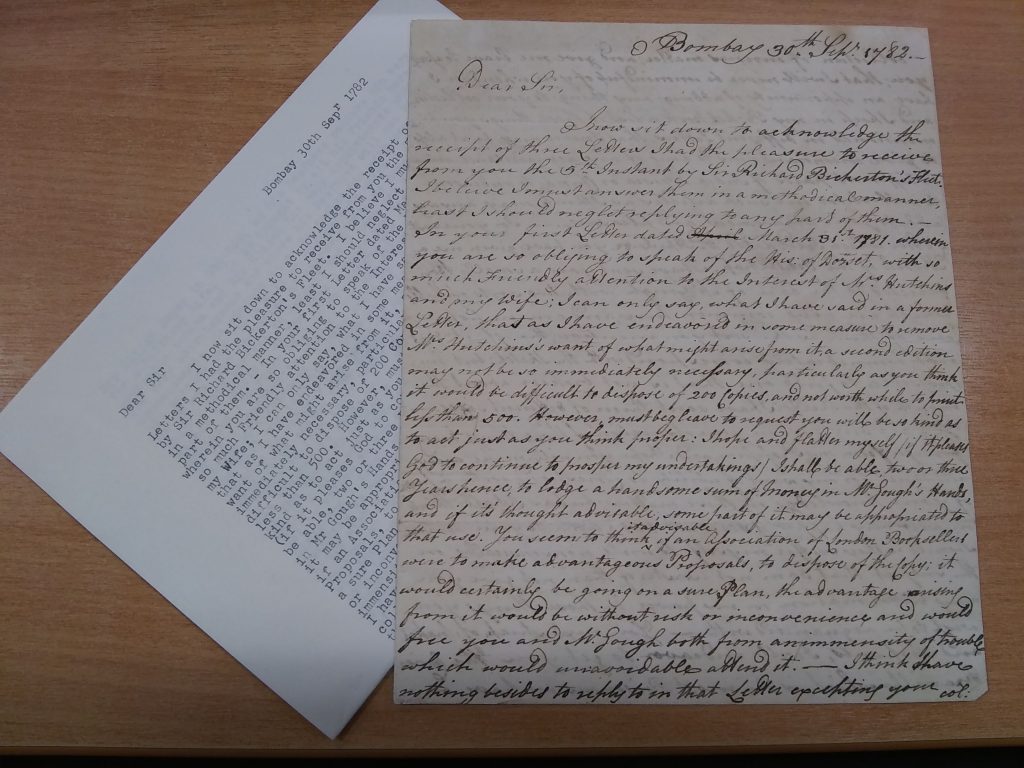

Hutchins died in 1773, the year before the first edition was finally published. Soon after his death his daughter travelled to Bombay and married John Bellasis, a commander in the East India company who went on to be governor of Bombay, where both he and his wife were buried. Bellasis was largely responsible for getting a second edition of his father in laws book published.

The trials that Hutchins faced in completing his work may have been expected in a project of such scale. The later editions of the works, however were also beset by problems.

The second edition was nearly destroyed by a fire in the printers in 1808, when only two of the four volumes had been printed. John Bellasis died suddenly only a few days later and Richard Gough, the edition’s main editor died the next year. At this point the completion of the edition was in doubt, but was eventually finished by John Bowyer Nichols.

The third edition was published in four volumes in 1861, 1864, 1868, and 1873. This edition was edited and printed by William Shipp and James Whitworth, although their partnership was apparently dissolved at some time during the creation of this edition as Whitworth is only listed as co-editor of seven of its fifteen parts. The printer of this edition, John Gough Nichols, died before the work was published and William Shipp died suddenly in 1873, leaving the final completion of the project to his widow.

None of those mentioned above were young men when they died, and perhaps it is too dramatic to call the book cursed, but in his 1973 reprint of the third edition Robert Douch offers a warning to all those who are contemplating work on John Hutchins and his History. He lists the above misfortunes before commenting that he himself had ‘suffered his first serious illness for thirty years while engaged upon this work’, so take heed anyone who is contemplating creating a fourth edition!!!

—

This blog is part of our monthly series on the 12 extra-illustrated volumes of “Hutchins’ History and Antiquities of Dorset.”

Part one: An introduction to the history and antiquities of Dorset.

Part two: The Pitt family, a piano player, and a plague of caterpillars.

Part three: Coastline, Castles and Catastrophe

Part four: A Phenomenon, Fake News and a Philanthropist

Part five: Antiquities, Adventurers, and an Actress

Part six: A Gaol, a Guide and a Man of Great Girth

Part seven: Physicians, fires and false allegations

Part eight: Graves, Grangerising and a Man who wore Green

Part nine: Desertion, Drinks and a Diarist

Part ten: Music, medical miracles, and mills

Part eleven: Courtiers, Criminals, and Cuttings

Part twelve: An Abbey, the Arts, and the Athelhampton Ape