At Dorset History Centre, we have a team of highly knowledgeable and eager volunteers, all of whom we haven’t seen for some considerable time now! That doesn’t mean that they haven’t been in touch with us though, and one of our keen volunteers has written this blog, exploring how parchment was made…

—

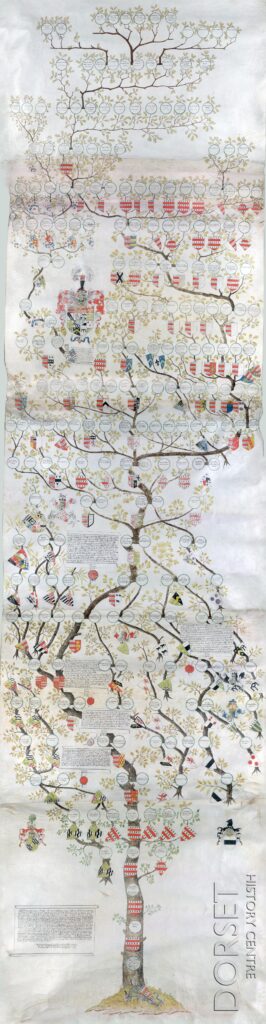

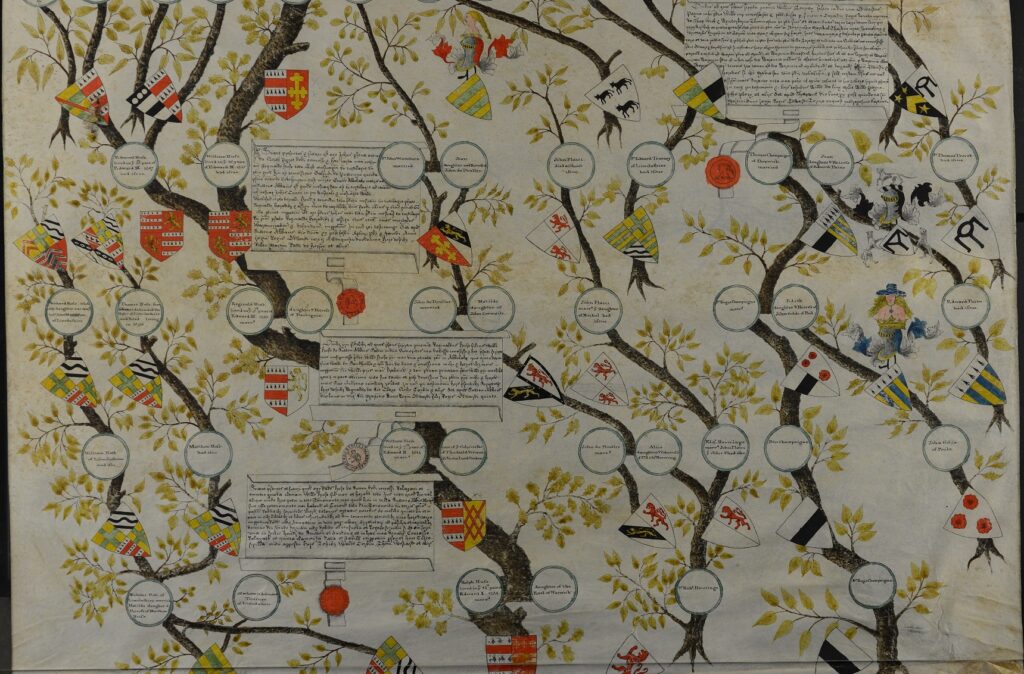

D-GIM is one of DHC’s larger collections, and one of it’s documents has graced the DHC leaflet for some time. This beautiful and enormously long family pedigree was drawn on parchment in around 1596. Parchment makes up a generous proportion of the records at DHC and we wanted to look into how it was made…

People experimented with the skins of sheep, goats and cattle but found the most successful skin to work with was that of an unborn calf, because it was so soft. One parchment maker could deal with 20 skins in a day.

After being flayed, the skin was soaked in water for about a day, then soaked in vats of lime for up to eight days, which dissolved the hair and the fat underneath and left the strong, collagen fibres. They were scraped over a barrel, stretched out taut onto a frame and ‘nailed’ in place. Nails were either made of ‘buttons’ of screwed-up paper to keep them in the right position, or the skins could be attached by wrapping small, smooth rocks in the skins with rope or leather strips. Both sides would be left open to the air so they could be scraped with a sharp, semi-lunar shaped knife to remove the last of the hair and get the skin to the right thickness.

The skins would form a natural glue while drying and once taken off the frame they would keep their shape and size. This stretching aligned the fibres to be nearly parallel to the surface, making them easier to write on. If they dried too quickly they became too rigid and transparent, if they dried too slowly they would become mouldy and smelly. Nothing was wasted. The skin was trimmed to the size needed for the document and any excess was used to make glue which then enabled the writer to stick pages together.

Different treatments were used to produce different effects. Most were rubbed down with chalk or pumice powder on the flesh side of parchment while it was still wet on the frame – this made it smooth and to modified the surface to enable inks to penetrate more deeply. Scalding and treating with pastes of calcium carbonate were used to help remove grease so the ink would not run.

In the later middle ages carbon ink, made from soot and gum mixed with water, was sometimes used. This formed a very black ink, but it simply adhered to the surface of the page rather than bonding into it. Carbon ink was used in early printed books. The ink could be scraped off, because it is not absorbed by the skin, so if there were any mistakes made, they could be corrected. Conservation/repairs are made with gelatine – a natural protein – used to act as glue where the original has stopped sticking the sheets together.

Parchment is extremely sensitive to changes in humidity, which can cause buckling. Current thinking about preserving these colourful, valuable and rare documents is to interfere as little as possible. They are stored in strong-rooms with controlled levels of temperature and humidity which slows any natural deterioration process. However, if a parchment document is particularly damaged or at risk of harm when accessioned our expert conservator can carry out minimal intervention treatments to ensure the document’s survival for many years to come.

The only parchment producer in England now is a company called Cowleys, in Newport Pagnell.