When researching your family history, you may discover one or two ‘Skeletons’, one possibly being that an ancestor was illegitimate. This is normally discovered when looking at their baptism record where, not only is the mother the only named parent, but the child is recorded as a ‘bastard’ in the register.

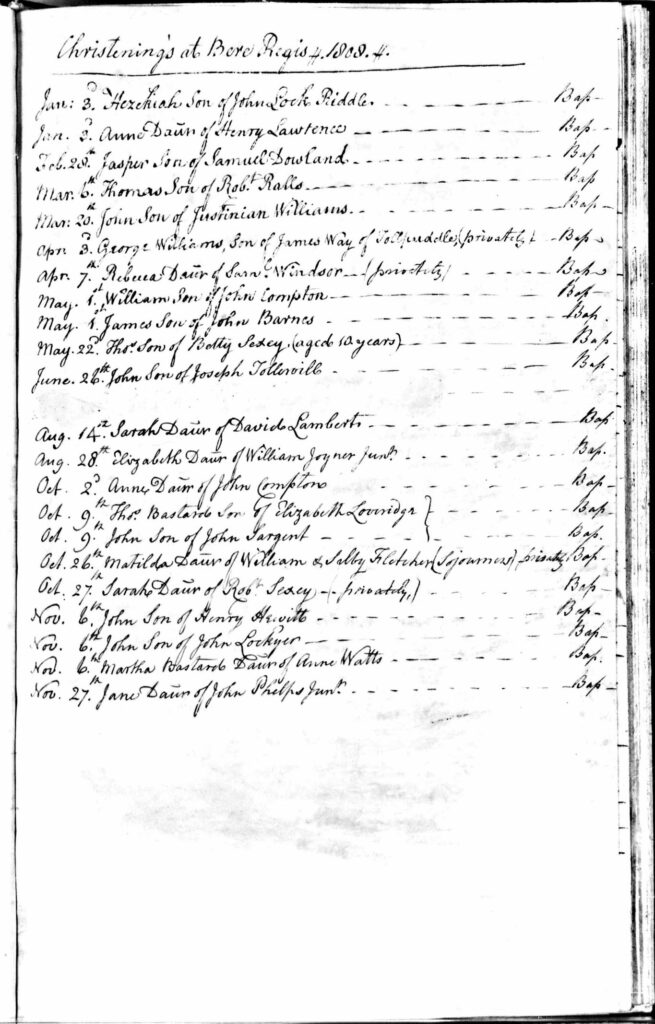

In the example below, from the baptism register for Bere Regis, it records a Thomas, Bastard son of Elizabeth Loveridge baptised 9th October 1808 and Martha, Bastard daughter of Anne Watts baptised 6th November 1808:

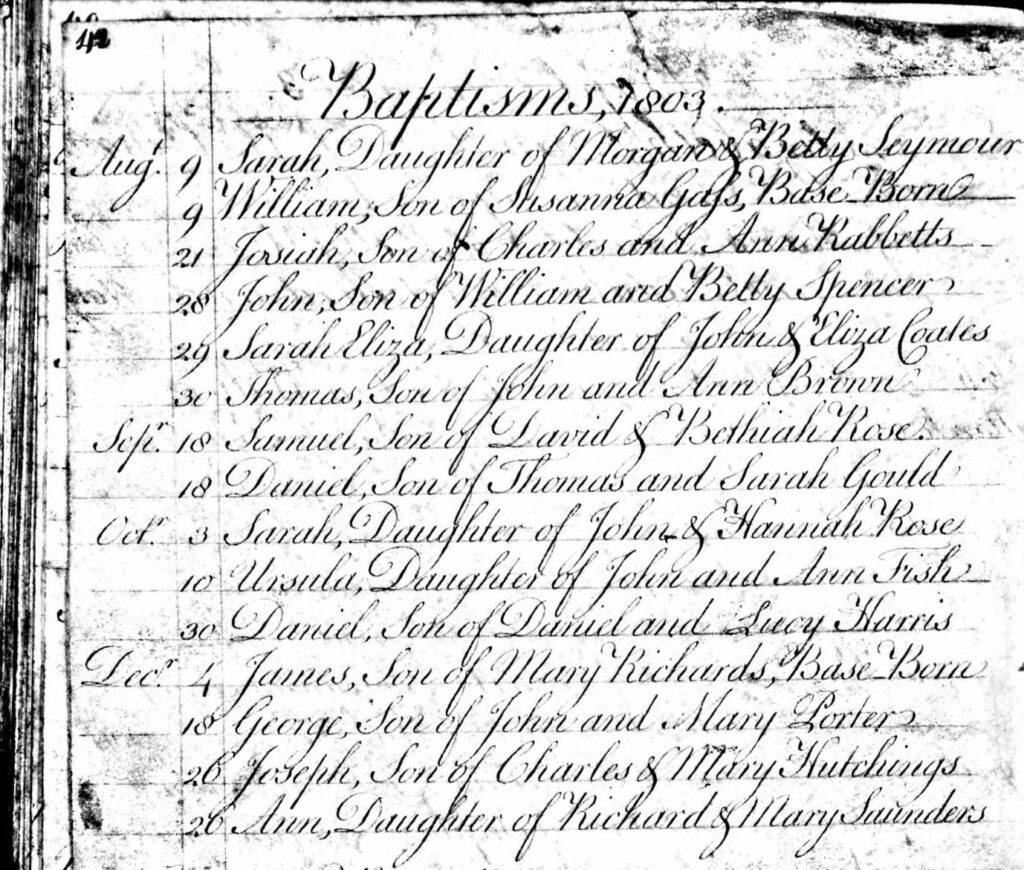

Sometimes the phrase ‘Base Born’ was used instead as can be seen in the Sturminster Newton baptism register below for William son of Susannah Gass, Base Born, baptised 9th August 1803 and James son of Mary Richards, Base Born, baptised 4th December 1803:

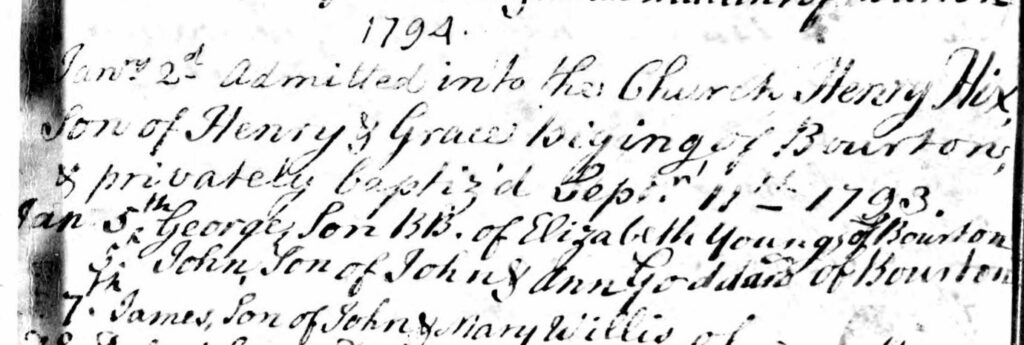

Occasionally this was shortened to just B.B as in the baptism register of Silton for George Son BB. of Elizabeth Young of Bourton baptised 5th January 1794:

Following the Poor Laws of 1601 if the father was not known then the cost of keeping an illegitimate child fell to the parish. Therefore, parishes tried to identify the father and make him legally responsible for the child’s maintenance to keep the child off the parish relief rolls. Documents within some parish records show not only how they sought to find the father in cases of Bastardy, but also to make him pay for the child’s upkeep. These Bastardy Papers, where they still exist in Parish records, fall into four categories, Bastardy Examinations, Bastardy Bonds, Bastardy Warrants and Bastardy Orders. These documents may assist you in possibly finding out who the reputed father of the child may have been. The examples that follow all come from the parish of Bere Regis in Dorset.

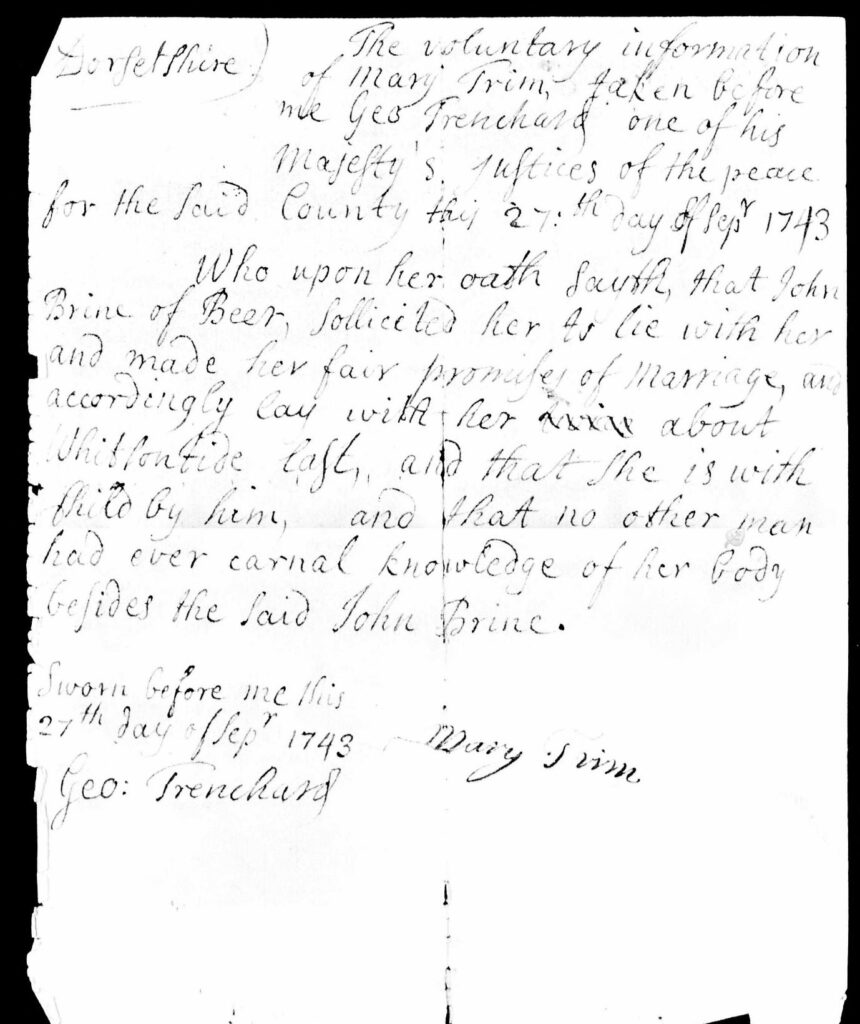

In Bastardy Examinations the mother of the illegitimate child is named as well as the reputed father. The mother may have gone voluntarily to the local Justice of the Peace, or she may have been summoned and required, under oath, to give the name of the child’s father. These powers of investigation were established under the Bastardy Act of 1575.

In the example below Mary Trim appeared before the Justice of the Peace on the 27th September 1743 where she swore that

‘John Brine of Beer, solicited her to lie with her and made fair promises of marriage and accordingly lay with her about Whitsuntide last and that she is with child by him and that no other man had ever carnal knowledge of her body besides the said John Brine’

Following the Examination, the parish would then pursue the reputed father. They would then be expected to either marry the mother or pay either a weekly maintenance or lump sum to support the child. These documents were known as Bastardy Bonds. There was usually a guarantor required to countersign the bond who would become liable if the father defaulted, often a relative with money or assets. However, it was not always the child’s reputed father who entered into the bond; churchwardens, overseers, friends or other benefactors might have undertaken this responsibility. The maintenance usually lasted until the child was old enough to be apprenticed out.

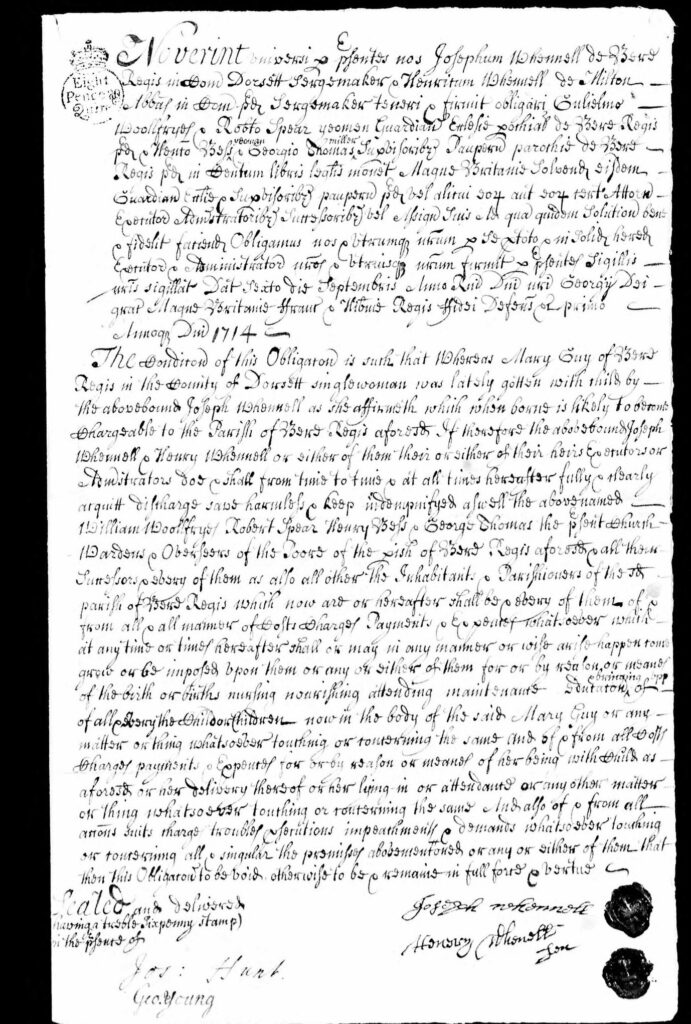

In the bastardy bond below, dated 6th September 1714, parish officials sought to obtain maintenance for Mary Guy of Bere Regis, singlewoman, who ‘was lately gotten with child by the above bound Joseph Whennell’. The bond bound both John Whennell, the reputed father and Henry Whennell, the guarantor, responsible for payment of the maintenance:

If the man denied they were the father of the illegitimate child and refused to sign a bastardy bond, then the overseers could apply to a local magistrate for a Bastardy Warrant to be issued. Once a warrant was issued the local constables were then able to apprehend the reputed father and bring him before a justice of the peace, or provide sufficient surety for his appearance at the next quarter sessions court. If he were required to attend the next quarter sessions and could not provide surety, he could be held in prison until his appearance. Bastardy warrants could also be issued if the father absconded or failed to pay the agreed maintenance.

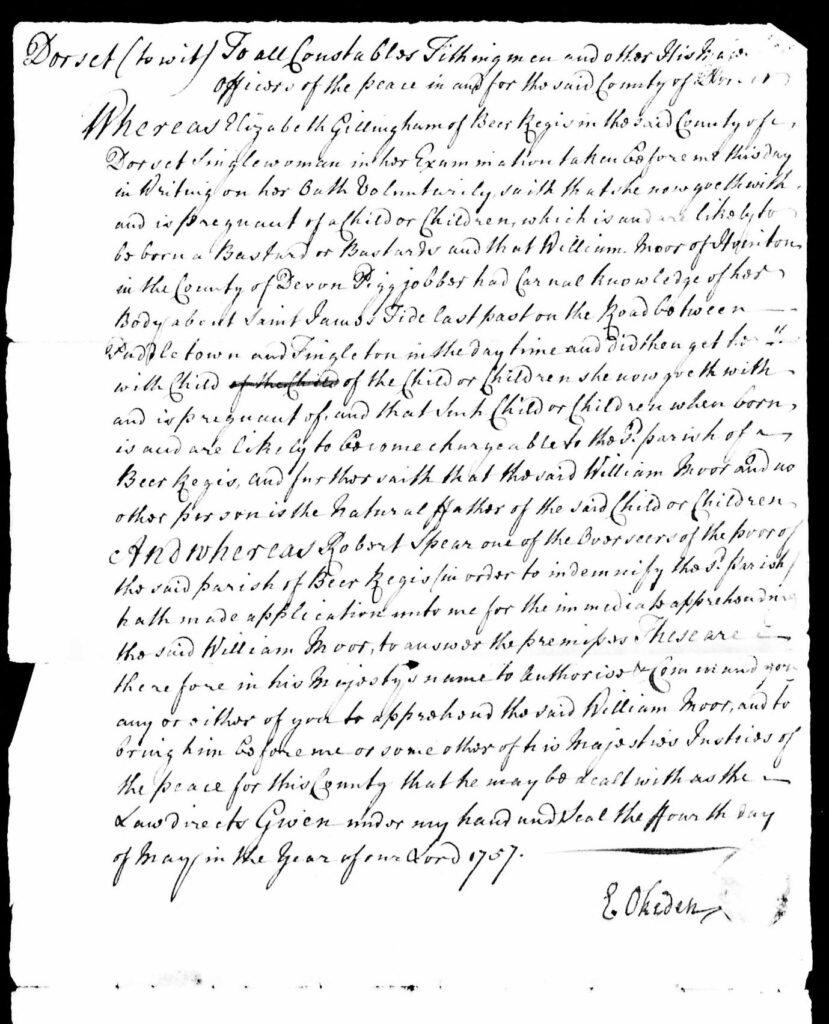

In the example below a warrant was issued against William Moor of Honiton, Devon, pigjobber, the reputed father named in the bastardy examination of Elizabeth Gillingham of Bere Regis, single woman, dated 4th May 1757:

When the reputed father appeared before the Justice of the Peace, he would be given an opportunity to admit paternity and either marry the woman or sign a bastardy bond.

However if they still denied they were the father, unless they could prove it was not possible to be the father (for reasons such as being at sea, abroad or in prison) then in all likelihood the Justices of the Peace would issue a Bastardy Order detailing how much they had to pay weekly to the Overseers of the Poor for the maintenance of the child.

Men who still disputed paternity could take their case on to the quarter sessions court, but it was very difficult to provide the proof required to overturn these orders. If he failed to convince the court, he would also be liable for costs.

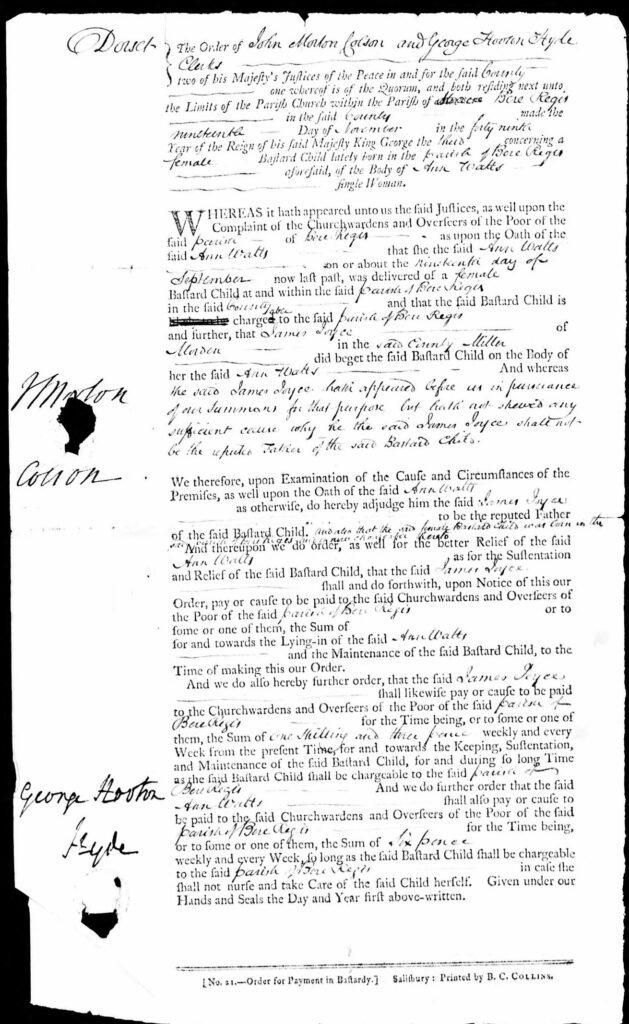

In the example below, dated 19th November 1808, James Joyce of Morden, Miller, the reputed father, was issued with the Bastardy Order to pay for the maintenance of the bastard child of Ann Watts as he

‘hath not shewed any sufficient cause why he the said James Joyce shall not be the reputed father of the said bastard child’

However, despite all these documents giving the mothers name and the name of the reputed father, the child’s name is rarely given with them often being referred to as just the ‘bastard child’.

Bastardy Records, for various Dorset parishes dating between 1725 and 1853, are available to view on Ancestry.com or in person at the Dorset History Centre.

high i need some help with a relative of mine

ann quaint born 12 th november 1610

wavenden bucks but was buried in london

she had married john bennett 25th august 1631

could anyone help me with her birth

on her birth certificate ther was no sign of her

parents what does this mean thanks for your help

trish patriciafeeney56@gmail.com

Hi Trish – please can you send us an email (archives@dorsetcouncil.gov.uk) and one of the team can look into this further for you!

I am looking for information on a distant grandmother called Hannah Hoskins. She is described as illegitimate, though she was born in the middle of Hoskins siblings. She was born in Beaminster in 1688 and I believe that her father was a Horsford. I would like any further details there are from the Bastardy Courts at that time and whether you could help me in this matter.

Dear William, thank-you for your comment. Your query has been passed along to one of the team here at Dorset History Centre, and they will be in touch with you directly in due course after the festive period.