The idea of ‘Remembrance’ as a period of reflection on the atrocities of war, and the lives of those who have been asked or compelled to go and fight in them is one which continues to resonate with people. This may be because rather than the ‘war to end all wars’ actually ending all wars, the 20th and 21st Centuries have continued to be littered with examples of predominantly young people being asked to fight for their country. Remembrance of sacrifices therefore continues to be as pertinent today as it was when they first really began, in November 1919.

But has the meaning of Remembrance changed in the intervening century? In 1919, over 880,000 British soldiers had been killed during the events of the First World War. A further 1.5 million had been injured. Communities had been decimated due to the earlier emphasis on Pals Battalions. Almost everyone had been involved in the war in some way, directly or indirectly. People were able to actively remember someone they had known who had been lost; the repercussions of the conflict on society were there to be seen. Remembrance of something was an almost tangible thing. People would directly remember a son, a husband, a father, or just a neighbour. They could close their eyes and picture a specific face of someone they had known. In the cases of 1.5 million people, they could close their eyes and remember the atrocities they had seen and experienced on the battlefields.

In 2021 this is no longer the case. The large, all-encompassing conflicts of the first and second world wars have almost drifted out of living memory, and in their place have stepped smaller (but no less devastating) conflicts – Northern Ireland, the Falklands, Afghanistan and others. Due to the smaller scale of these conflicts, naturally fewer people have been directly impacted by them. As a consequence, this alters the very nature of ‘Remembrance’. Indeed, the larger question may be- who are we remembering if we have nobody to directly remember? Are we remembering just the ideas of these soldiers based on photographs? Are we simply remembering that these conflicts have taken place, suggesting that remembrance is less about the ‘who’ as it is about the ‘what’?

In 2018 Dorset History Centre hosted a very engaging debate on these very issues. The event, with a large audience, lasted 90 minutes, and provoked a good number of ideas, thoughts and opinions, highlighting that the issue of ‘remembrance’ is one which still carries lot of meaning in the 21st Century. The recording is available at Dorset History Centre to listen to if you are interested in the thoughts of Kate Adie, Stephen Boyce (of HLF South West), Symon Hill (from the Peace Pledge Union) and David Willey (Curator of the Tank Museum).

—

But are there any more indications in the archives of the changing nature of ‘remembrance’?

We wanted to explore (in a reasonably limited way) how remembrance services might have changed in Dorset since the end of the First World War. Dorset History Centre hold various parish collections, in which there are programmes and planning information about these services. By the very nature of their provenance, these collections reflect the religious nature of ‘remembrance’. We also hold photographs of remembrance service events. It is worth noting that more secular Remembrance does and did occur, but this is poorly represented in our collections, so will not be the focus of this blog.

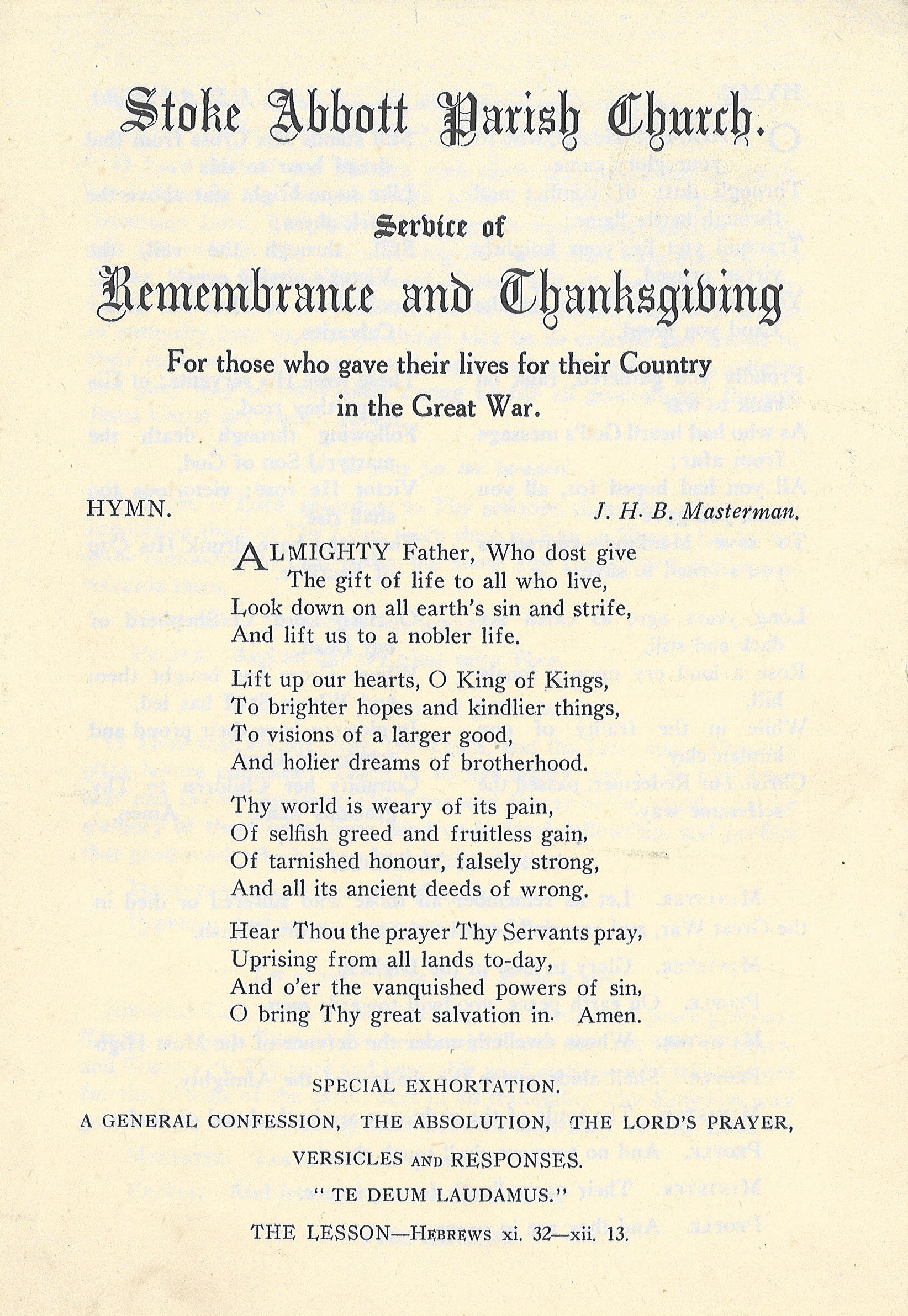

To start, in we have a simple order of service from Stoke Abbott, from c.1918. Coming as soon as it did after the end of WW1, this programme is brief and to-the-point. It comprises of three hymns, a selection of prayers, a sermon, and a note that a collection would be taken for the British Legion. There is no indication of parades for the fallen, no officials from different walks of life. The implication is clear – remembrance was understandably raw, private, and full of emotion at this point. Perhaps anything more than a sombre reflection with a small, reserved service, would have been difficult to for those who had survived the war?

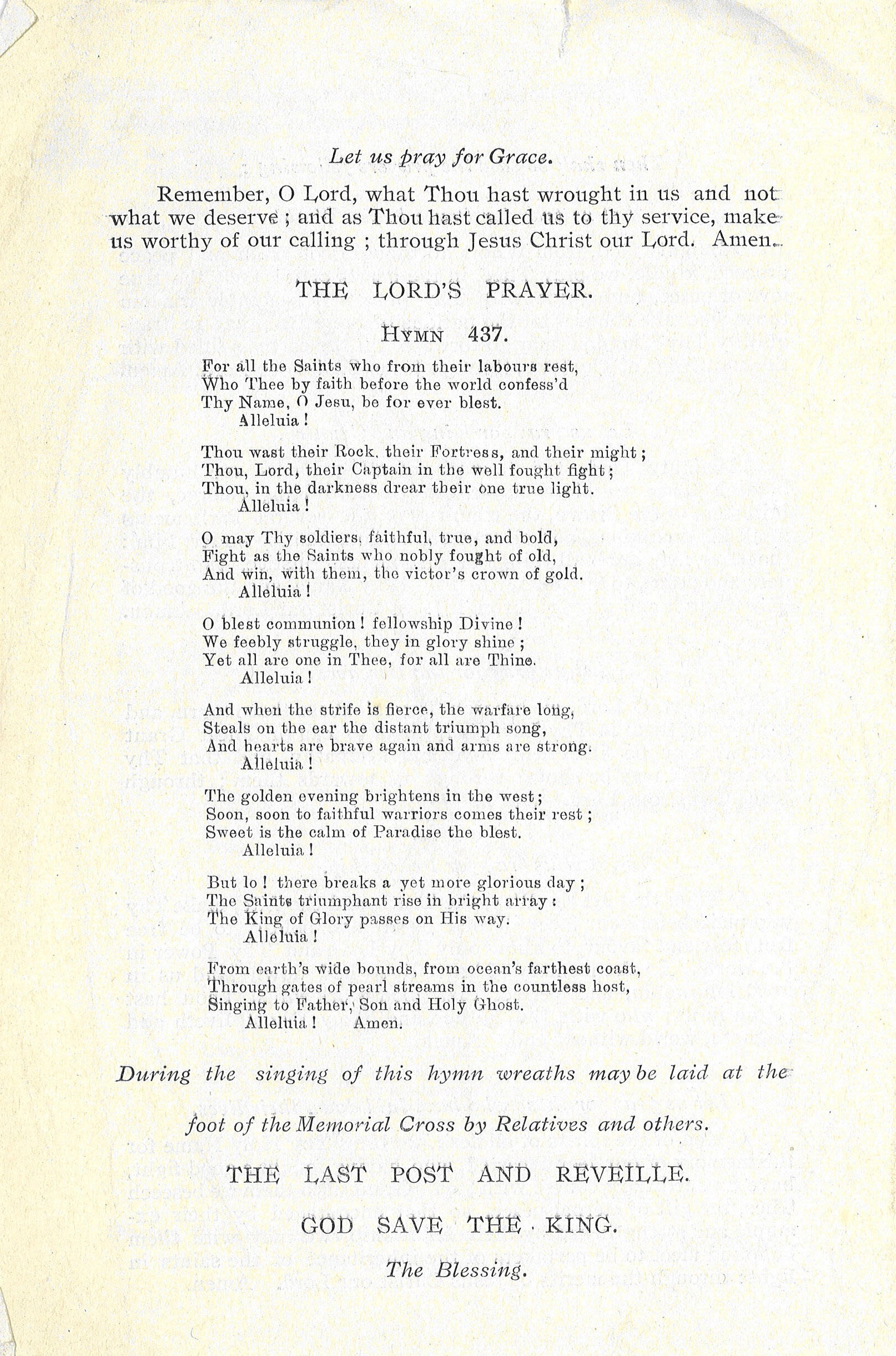

By 1926 this had already subtly changed however, as we can see from a similar Order of Service from Sturminster Marshall. In the space of a few years, the event that was ‘remembrance’ had evolved. Whilst hymns, prayers and a sermon were all still part of the event, lines at the end reveal this evolution:

“During the singing of this hymn wreaths may be laid at the foot of the Memorial Cross by Relatives and others.

THE LAST POST AND REVEILLE.”

This idea of ‘Remembrance Day’ had grown from 1920 onwards, with the burial of the unknown soldier at London’s Cenotaph, and the advent of the Royal British Legion selling poppies. It is therefore no surprise to see this idea of wreath laying now reflected in 1926.

The addition of the words “and others” is also indicative of change. Relatives of those lost in the conflict were still important, but ‘others’ suggests that non-relatives were part of the event of wreath-laying. Perhaps these were simply friends; perhaps they were others who had experienced loss but were unrelated to the parish; perhaps they were even officials acting in an official capacity. Whatever the answer, there is indication that ‘remembrance’ had perhaps grown from the deeply personal to something slightly larger as early as the 1920s.

—

Of course, this would evolve further in the aftermath of the Second World War, as a new generation of people lived through six years of conflict. There were any number of things which changed as a result of this period, including the public acts of remembrance. By its very nature, the Second World War caused a swelling of people affected by conflict. ‘Remembrance’ had got bigger as there were now multiple generations of people alive at the same time who had lived through both conflicts.

In a photograph of Dorchester from c.1950 we see a procession of suited men, medals pinned to their chests, following the flag of the British Legion. The line is long, and notably, the men are generally older. Were these volunteers who formed the Home Guard during WW2? Are any of them old enough to have experienced WW1? Are they remembering fallen friends?

—

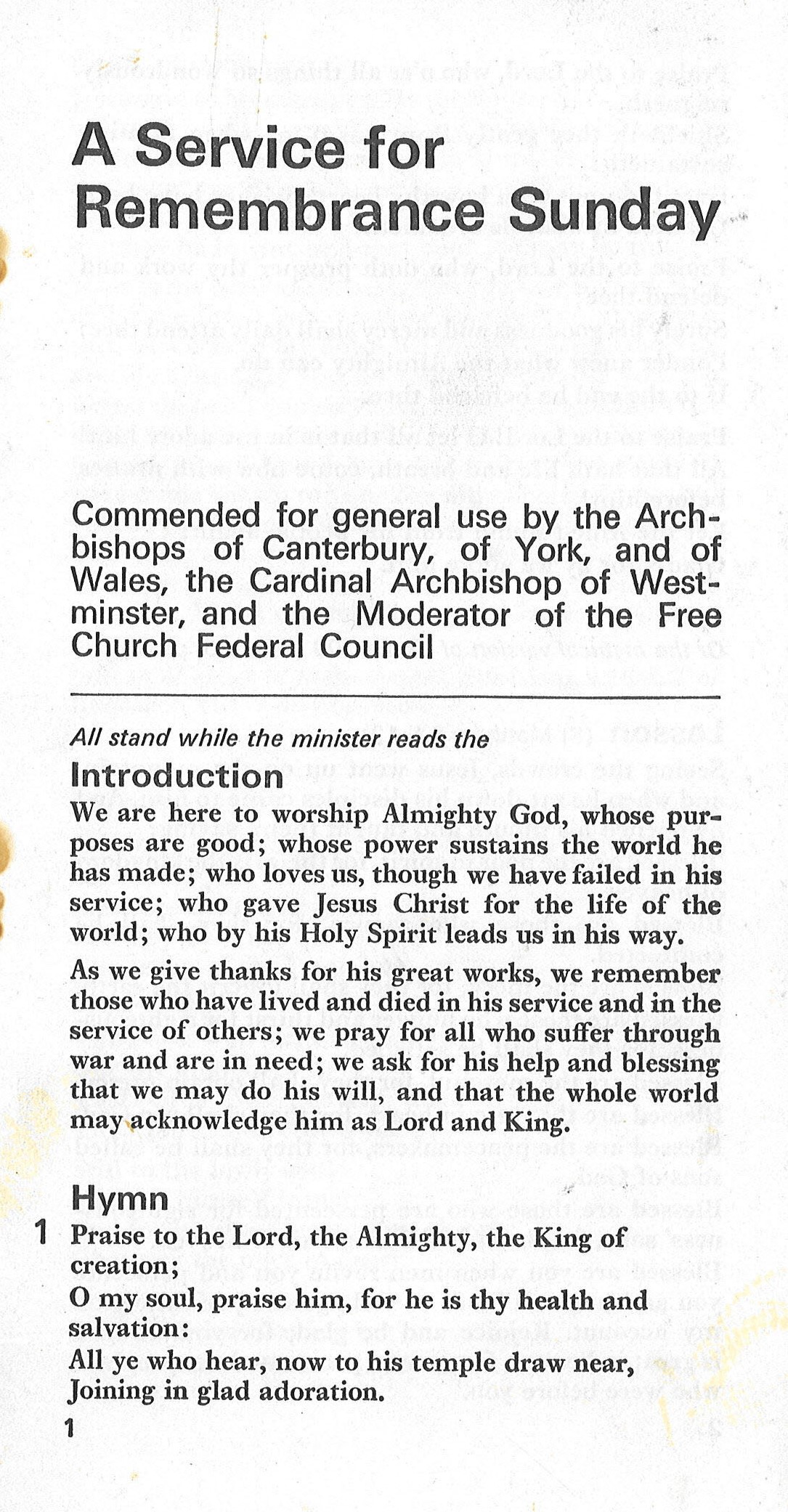

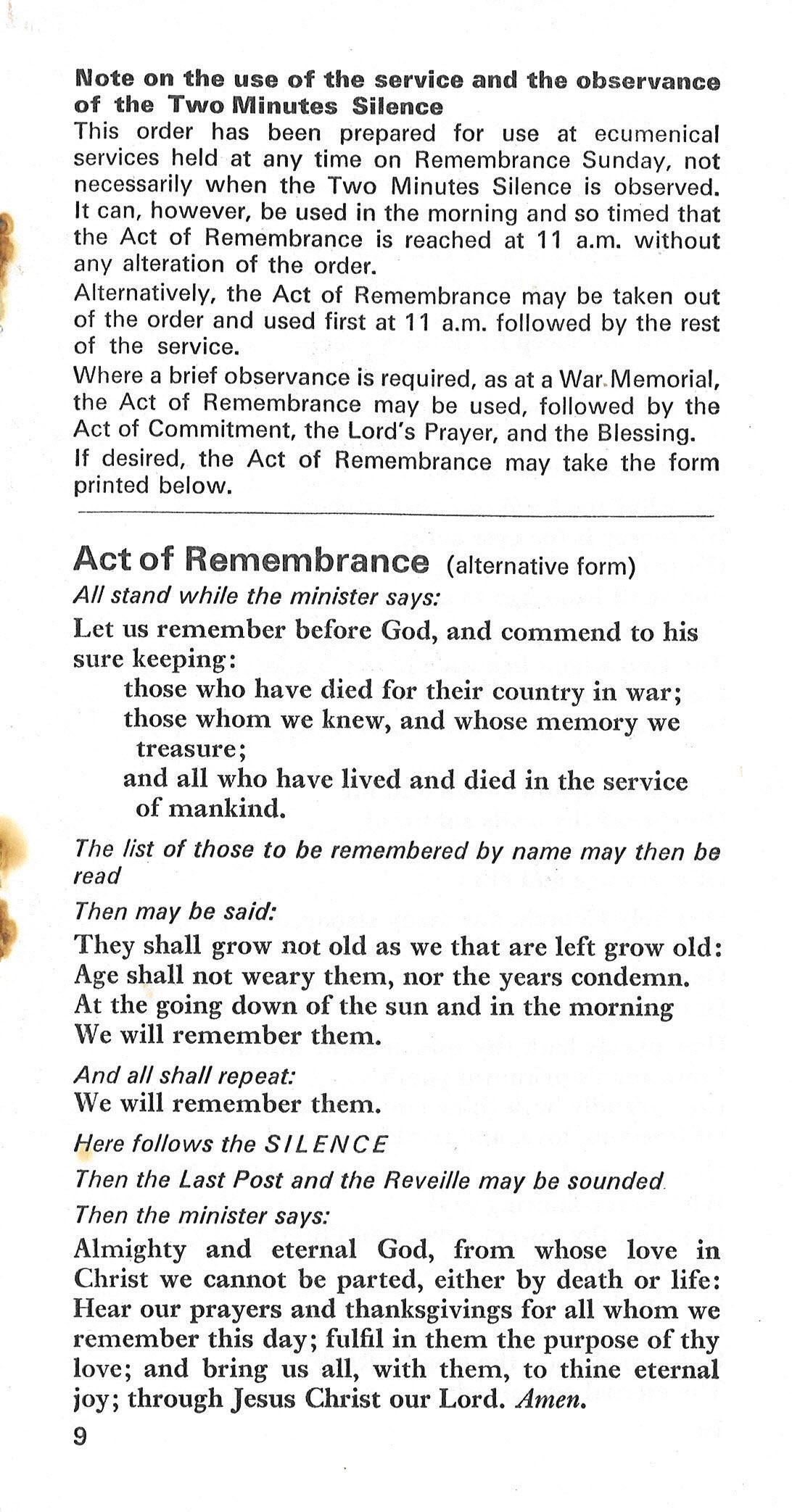

By 1968, Remembrance services were once again larger in size and ceremony. In Horton, we see a larger ceremony than we saw in the 1920s. There was more ‘gesture’ to the service than had been seen previously. The order of service was now more complex, issued now by the Church,

“Commended for general use by the Archbishops of Canterbury, of York, and of Wales, the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, and the Moderator of the Free Church Federal Council”

Services, it appears, were no longer necessarily about the ‘local community’. Long gone were the days of smaller ceremonies with quiet reflection and mourning. Remembrance was now as much about the act of remembering as it was about the meaning, and therefore needed instruction from authorities. The order of service was now a 12-page document, something of a dramatic increase in scale from the folded pages of A4-sized paper, printed front and back that we have previously seen.

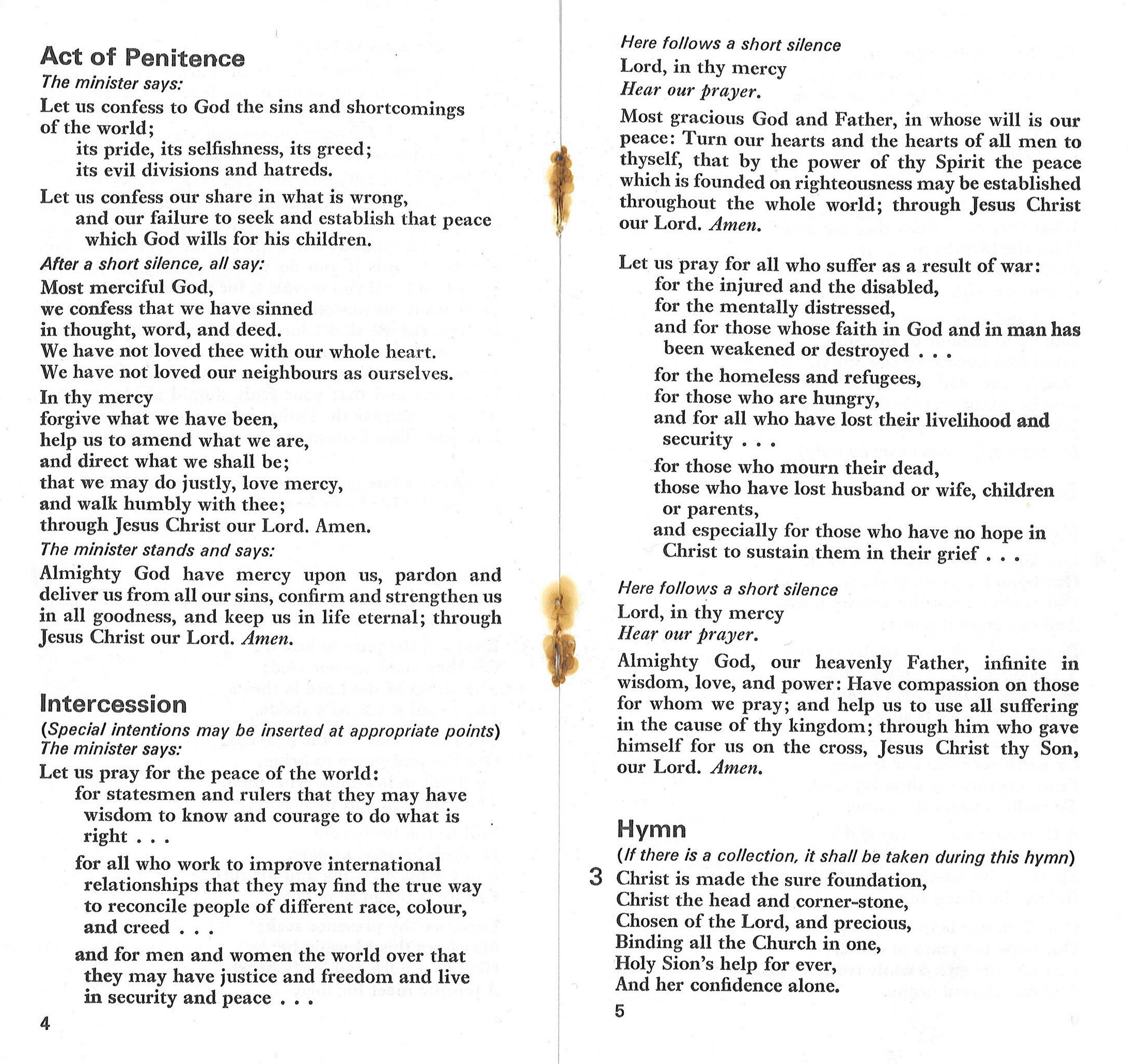

Even more reflective of the changing times was the Intercession. The first prayer offered is notable in that it is not a prayer for those directly affected by war, instead it is a prayer

“for statesmen and rulers… for all who work to improve international relationships…and for men and women the world over”.

This is then later followed by a prayer for “all who suffer as a result of war”. Finally, midway through the service, do we first see any reference to ‘remembrance’, with a prayer remembering

“those who have died for their country in war;

Those whom we knew, and whose memory we treasure;

And all who have lived and died in the service of mankind.”

Later in the booklet, there is further guidance, with an alternative Act of Remembrance, designed for use at a War Memorial rather than during a church service, with a fuller piece relating to remembrance, including the instruction:

“The list of those to be remembered by name may then by read”

It is clear that by the 1960s, what it was to remember had changed from local and quiet mourning, into something more… official.

—

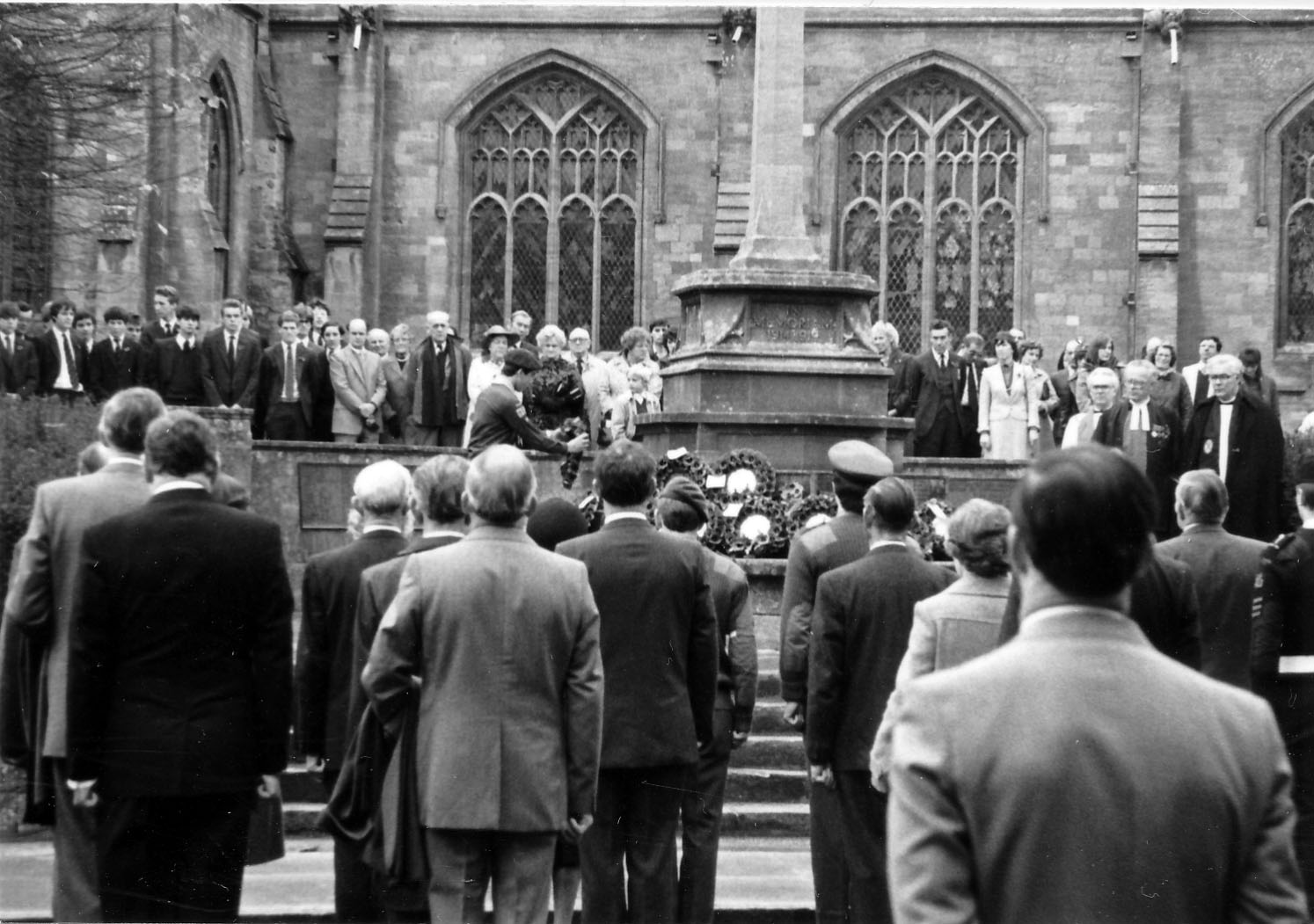

This change into something more official is further borne out by later images. In the collections at DHC, we hold some images of Remembrance Day parades from the 1980s. A series of photos (D-DPA/1/SH/105-114), from Sherborne, demonstrate that remembrance services now came complete with marching brass bands, ex- and current servicemen and women, dignitaries, schoolchildren and others. Private reflection has clearly long been replaced by public demonstration by this point.

Which moves us onto remembrance in the 21st Century, and a society long-removed from the horrors of either World War, but still bearing the scars of smaller, more recent conflicts. Discussions continue about poppy wearing, the colours of the poppies worn, and when they should be worn. However, remembrance has become more inclusive – the impacts of war on many different communities, nationally and internationally is now seen. We still have parades of ex-servicemen and women, and services in memory of those who have fought in conflicts. And whilst it is obvious that we no longer necessarily remember someone specific when we pause for two minutes on 11th November and Remembrance Sunday, we are instead, perhaps, remembering the lessons of the conflicts in the hope that they may never be repeated.