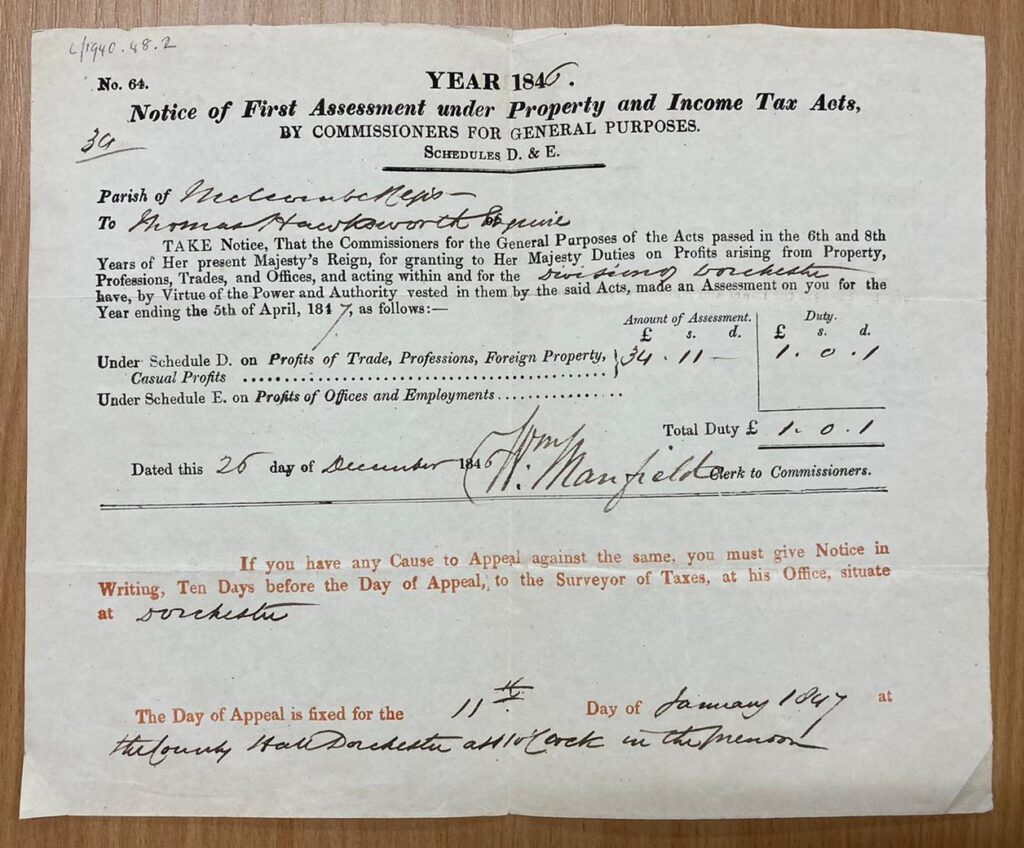

On the 26th December 1846 notice was sent from the Commissioners for General Purposes Act -Dorchester to one Thomas Hawkesworth Esquire of Melcombe Regis.

The document was a tax assessment due for the year ending April 5th 1847 to the sum of £34.11.00, duty payable £1.0.1 for sums to be paid for profits on property. An appeal date was supplied as 11th January 1947 at the County Hall Dorchester, should Thomas have caused to appeal the order.

The document was a notice of Assessment under the Property Act and cited schedules D and E. A further document relating to Assessed Taxes was sent to Thomas (undated in 1848) for the year ending April 1848 acknowledging duties of £5.3.4. being paid to the collector residing in Augusta Place Dorchester. Details of the assessment are provided in a document in list form showing £3.10.0 as Window Tax for 5 Windows and £4.0.0. for a Manorial Bearing. Date of Appeal given 29th September (1848).

These inauspicious tax documents are of interest as they give an idea of the links between the devastating events around this period in Ireland that of the Irish Famine and subsequent Poor Laws of 1847.

—

Thomas was the son of John (1775-1825) and Ellen Hawkesworth living in Forest, Mountrath; Queen’s County, Ireland[1]. John Hawkesworth was descended from a long line of Hawkesworth’s from Yorkshire dating back to the 16th century. The Genealogical Dictionary records John Hawkesworth to be a J.P. and Deputy Governor of the seat of Mountreath, Ireland:

‘The eldest son and heir John Hawkesworth, Esq. of Forest, J. P. and Deputy- Governor, b. 3 June, 1775 ; to. 23 May, 1799, Ellen, dau. of Richard Steele, Esq’.

– A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry, Part 90, Volume 1

He was associated with Charles Henry Coote, 7th Earl of Mountrath PC (c. 1725 – 2 March 1802), styled Viscount Coote until 1744, an Irish peer and landowner. Coote was the descendent of namesakes who had fought in the Battle of Kinsale in 1601 and the Cromwellian Wars. He was part of an Anglo-Irish Protestant Ascendancy who dominated Ireland economically, politically, religiously and culturally. They had replaced the Gaelic Irish and Old English Catholic aristocracy in the 17th century while the majority of the Catholic Irish were reduced to the status of tenants and landless peasants living in wretched poverty and surviving on a diet of potatoes[2].

—

Thomas Hawkesworth Esquire(1806-1881) married Sarah Francis Bain in Ireland in 1831 where their first son John William Bain Hawkesworth was born. His first daughter, Frances May Hawkesworth (Fanny – born about 1838), was born at Stoke Under Hamdon, Somerset. It would appear that Thomas’s mother had moved to Somerset sometime after the death of their father in 1825 and Thomas was living with, or nearby his mother whose recorded death was 2 May 1838, Yeovil, Somerset.

It is possible that it was at this time, on the death of his mother and birth of his daughter Thomas moves to Melcombe Regis, Dorset. Sarah is recorded as having been born in Bath Somerset adding a further family connection to the County.

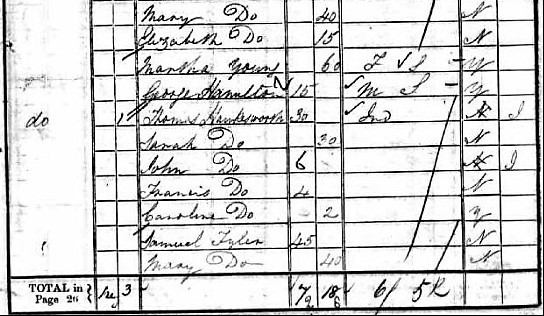

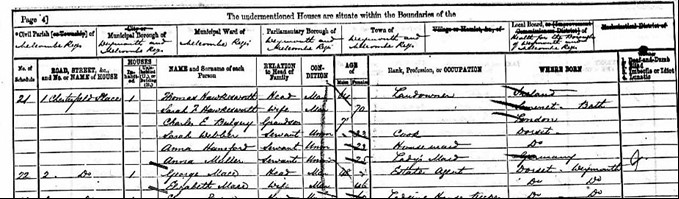

The census of 1841 finds Thomas and his family residing at 1 Chesterfield Place, Melcombe Regis. Records show that by this time Thomas had a third daughter Caroline Georgina Hawkesworth (1839–1922)[3].

The household is comprised of the young Hawkesworth family and Samuel and Mary Tyler likely servants. The profession cited for Thomas at this time was of ‘independent’ means:

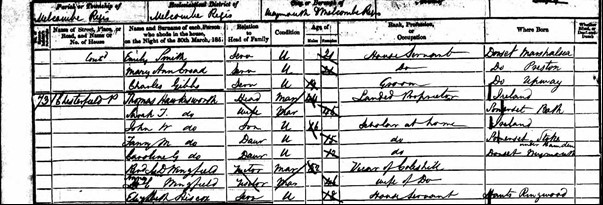

The census of 1851 shows the family and includes the Rev. Dr D Wingfield and his wife of Colehill , tutors to the children, and a house servant, Elizabeth Hiscox of Ringwood Hants. This census names Thomas with a status of ‘Landed Proprietor’, the indication that he was the owner of property thus linking to the tax assessment:

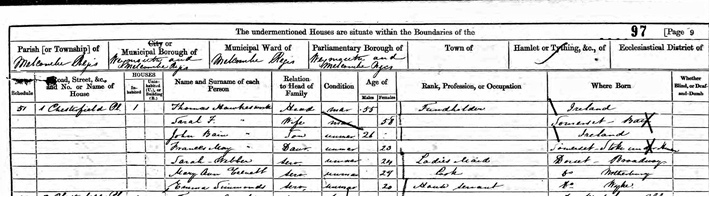

The census of 1861 refers to Thomas as a ‘Fundholder’. This record indicates the absence due the death of his daughter Caroline and the staff changes Sarah Webber (Ladies Maid), Mary Ann (Cook), and Emma Simmonds (House Servant).

By 1871 Thomas and Sarah were still at 1 Chesterfield Place but now had their 7 year old grandson Charles [Bulguy], born in London, living with them. Sarah Webber is now the family Cook, with new House Servant Anna Hanford, and from Germany, Ladies maid, Anna Muller. Thomas’s position continues to be ‘Landowner’.

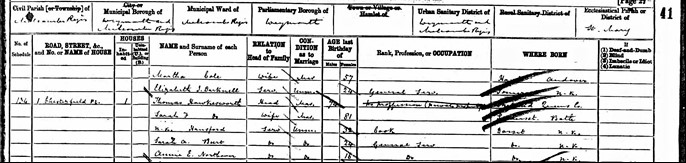

The final census for this family comes in 1881, with Thomas at 74 recorded as, ‘no profession (previously landowner)’ although this has been crossed through. Sarah Burt is a new general servant, Anna Hanford still Cook, and Thomas and Sarah still residing at 1 Chesterfield Place together.

—

Chesterfield Place in Melcombe Regis, now 59 Esplanade (now a Fish and Chip shop), was one of the prestigious fashionable Georgian residences in the flourishing seaside town of Weymouth made popular by Prince Henry Duke of Gloucester from 1765 and later King George III in 1789.

In the period when the tax assessment (that we started this blog with) was sent to Thomas Hawkesworth the Irish Potato Famine and Poor Laws were occurring in Ireland and,

‘the sight of tens of thousands of emaciated, diseased, half-naked Irish roaming the British countryside had infuriated members of the British Parliament. Someone had to take the blame for this incredible misfortune that had now crossed the Irish Sea and come upon the shores of Britain.

The obvious choice was the landlords of Ireland. Many British politicians and officials, including Charles Trevelyan, had long held the view that landlords were to blame for Ireland’s chronic misery due to their failure to manage their estates efficiently and unwillingness to provide responsible leadership. Parliament thus enacted the Irish Poor Law Extension Act, a measure that became law on June 8, 1847, and dumped the entire cost and responsibility of Famine relief directly upon Ireland’s property owners.

But in reality, many of Ireland’s estate owners were deeply in debt with little or no cash income and were teetering on the verge of bankruptcy. However, the new Poor Law would require them to raise an estimated £10 million in tax revenue to support Ireland’s paupers, an impossible task’.[4]

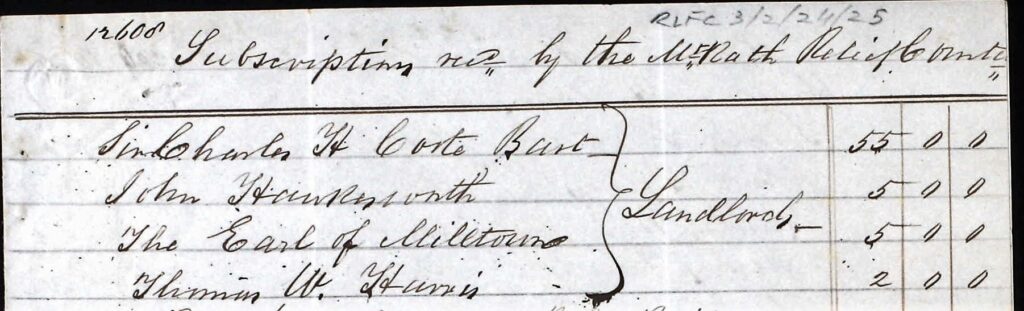

It was therefore encumbent upon John Hawkesworth and his sons, together with the aforementioned Viscount Charles Coote to contribute to the taxes on the properties rented to their tenants.

Thomas’s Assessment for tax refers to Schedule D which according to the Irish Tax Directory:

Schedule D

(iii) to any person, whether a citizen of Ireland or not, although not resident in the State, from any property whatever in the State, or from any trade, profession or employment exercised within the State;

Section E

- Tax under this Schedule shall be charged in respect of every public office or employment of profit, and in respect of every annuity, pension, or stipend payable out of the public revenue of the State, other than annuities charged under Schedule C, for every twenty shillings of the annual amount thereof.

13.—(1) Any person charged to income tax under Schedule E may appeal to the Special Commissioners against the amount of tax deducted from his emoluments for any year. [5]

It is not known at this point if Thomas appealed his due taxes to the estates in Ireland, but on the death of his father (1825) and brothers John (1829) and Richard (1878) under Section D he would still be liable for the taxes due.

The second Assessment for Window Tax and Armorial bearing would apply to his residence at Chesterfield Place according to the Landed Property (Ireland) Bill:

‘He found there were three great descriptions of taxation from which the Irish population were exempt. He found there were, first, the assessed taxes, which no Irishman paid. Now, let them understand what an assessed tax was. It was a tax upon a man’s house, upon his windows upon his servants, upon a variety of things—such as his horses, his armorial bearings…’ [6]

The Window tax:

‘This tax was first imposed in England in 1696. It was intended to be a progressive tax in that houses with a smaller number of windows, initially ten, were subject to a 2 shilling house tax but exempt from the window tax. Houses with more than ten windows were liable for additional taxes which increased in line with the number of windows.

As it was the landlord, as the property owner, who was subject to the tax, windows in tenement buildings were often boarded up….

The tax was repealed in 1851.[7]

—

It transpires therefore that the tax document sent to Thomas Hawkesworth Esquire on the 26th December as reminder to pay property taxes, informs us about a member of the Irish Landed Gentry involved in the shattering troubles of the Irish people in and around 1847. This, despite his relocation to a fashionable seaside resort, where he could afford a prestigious residence and comfortable life for his family with a continuing household of servants and tutors for children. This lifestyle was supported by an income that was provided by tenants from ancestral estates that he and his brothers had inherited and continued to own.

—

[1] In the beginning of the 17th century, the lands around Mountrath became the property of Charles Coote. Despite the wild surrounding country, which was covered with woodlands, he laid the foundation of the present town.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Coote,_7th_Earl_of_Mountrath

[3] http://www.opcdorset.org/WeymouthMelcombeFiles/Weymouth-Melcombe.htm

[4] https://www.historyplace.com/worldhistory/famine/ruin.htm

[5] https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/1967/act/6/enacted/en/print#sec52

[6] https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1847/mar/08/landed-property-ireland-bill