This is the fifth and final part of our series of blogs looking into the life of the author John Fowles through the records we hold here at Dorset History Centre. In previous posts, we have introduced you to the author John Fowles, his interest in Mary Anning, his life in and around Lyme Regis, and his interest in the town and community. In this, the final part of the series series, volunteer Graham has looked further into some of Fowles’ miscellaneous interests; and the latter part of Fowles’ life…

—

Some miscellaneous interests… and an opinion

Fowles’ notes and correspondence about Harriette Wilson are in the Collection.1 This was the adopted name of a popular courtesan; a family tradition since three of her sisters were also courtesans, but Harriette wrote two volumes of Memoirs, which included a description of her visit to Lyme:

“a sort of Brighton in miniature”

There is a file of Fowles’s notes and correspondence concerning the suffragette Sarah Bennett (1850-1924), who also used the aliases Susan Burnton and Mary Gray, and was arrested at least seven times.2 There is file of text and correspondence with Michael Taylor, author of The Interest: How the British Establishment Resisted the Abolition of Slavery, concerning John Hawkins, privateer, admiral and early slave trader.3

In 1988 Fowles came under pressure from his publishers to start using a word processor. He thought that “this must bring an impoverishment to the writer,” but admitted that

“my own worries and disinclinations must strike them [his writer friends] as highly theological.”4

It is easy to forget that his voluminous notes, recordings, and diaries were done, at least initially, by hand, even if many of them were later deciphered by a secretary and typed. The collection contains files of his transcriptions of Lyme parish records: poorhouse accounts, the poorhouse governor’s book, poor law assessments, apprenticeship book, pew tenancies etc.5

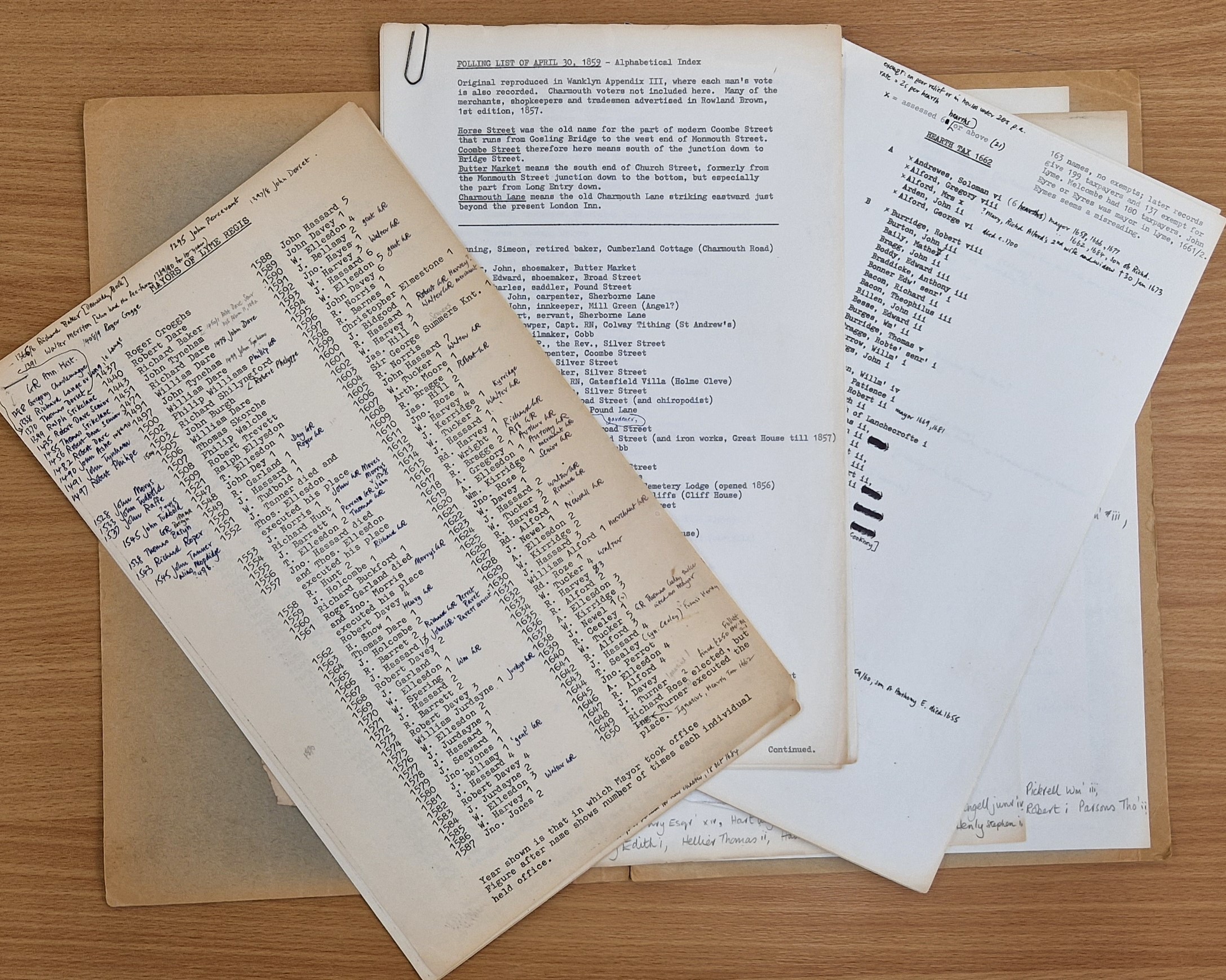

A file of “lists of Lyme people from assorted historical documents” is likely to be of interest to family historians,5 as will Fowles’s lists of Lyme residents and voters from the years 1782, 1785, 1793, 1812, 1819 and 1833.3 But he also liked to collect more unusual information. For example a list of Lyme nicknames: some gleaned from other collectors of such information, and perhaps not so very useful since many of them cannot be connected to the individuals who bore them.6 There is a file on “Dorset and West Country dialect and folklore” with transcripts, notes and drafts associated with Frank Palgrave.7 Was this the Rev Francis Milnes Temple Palgrave, or his father Sir Francis Temple Palgrave, author of The Golden Treasury, who wrote a poem about the hamlet of Harcombe, near Lyme?

Then there are “brief notes and correspondence regarding witchcraft”, including an exchange with his friend Dr Hudson of Beaminster seeking a modern medical explanation of illnesses which might have caused the witch’s symptoms; on balance Hudson thought the symptoms might all be attributable to “hysteria”1. Fowles also checked on the local families involved: Way (also spelt as Wea or Wey), Traull (also Troll, Trool, Trawl or Thrawl), Callway (also Kellway or Kelaway). Hudson was clearly a close friend who also advised him on appropriate medical symptoms and prognosis for a character in one of his novels.

Finally for this section, it is also worth noting Fowles’s firm opinion of the 1977 jubilee celebrations. He wrote of

“the horrors of the Jubilee;”

“the absurd and Gadarene rush to celebrate … which seems infinitely remote from anything to do with modern Britain and problems;”

and

“so many absurd gentlemen dressed up in their ancient finery: pure theatre, and pure cultural hegemony.”8

—

The Philpot Museum and after

Following his stroke Fowles resigned from the Lyme Museum in February 1988, seventeen years before his death. His successor as curator was Liz Anne Bawden, a town councillor who had also supported the Town Mill campaign; she gave him the title of Honorary Archivist9. As soon as his health permitted he continued with his own writings, researches and journals, as well as supporting the researches and publications of other writers. The Fowles Collection in the Dorset History Centre reflects the outcomes of many of these efforts from both his time as curator and from later years.

Fowles had written the foreward to The First Fifty Years of the Lyme Regis Society, published by Dr Joan Walker in 1984. The Collection contains a file of his notes and correspondence with her10. In 1993 Lyme Voices was published, the memories of Selina Hallett and Ivy Caddy, again with a foreward by Fowles. The Collection contains a file of correspondence, notes and drafts of Lyme Voices, as well as several files of his transcripts11. Hugh Gundry Flambert was recorded in 1903 as a coal merchant in Broad Street; the Collection holds a file of his “notes and transcripts of reminiscences”12. There is a file with a photocopy diary, transcripts, notes and photographs of a James Bridle13. Another file contains “notes and draft text for a Jack Holmes”14.

In Lyme the Henley family had been successive Lords of the Manor, and Henry Henley was responsible for bringing the Fane family of Bristol to Lyme. They dominated the town politically from around 1750 until the Reform Act in 1832. According to Fowles in his 1982 A Short History of Lyme Regis the Fanes “had no human interest whatever in the town and ran it with a ruthless contempt for its ancient freedoms and privileges.” The Fowles Collection holds two files regarding the Fane and Henley families.

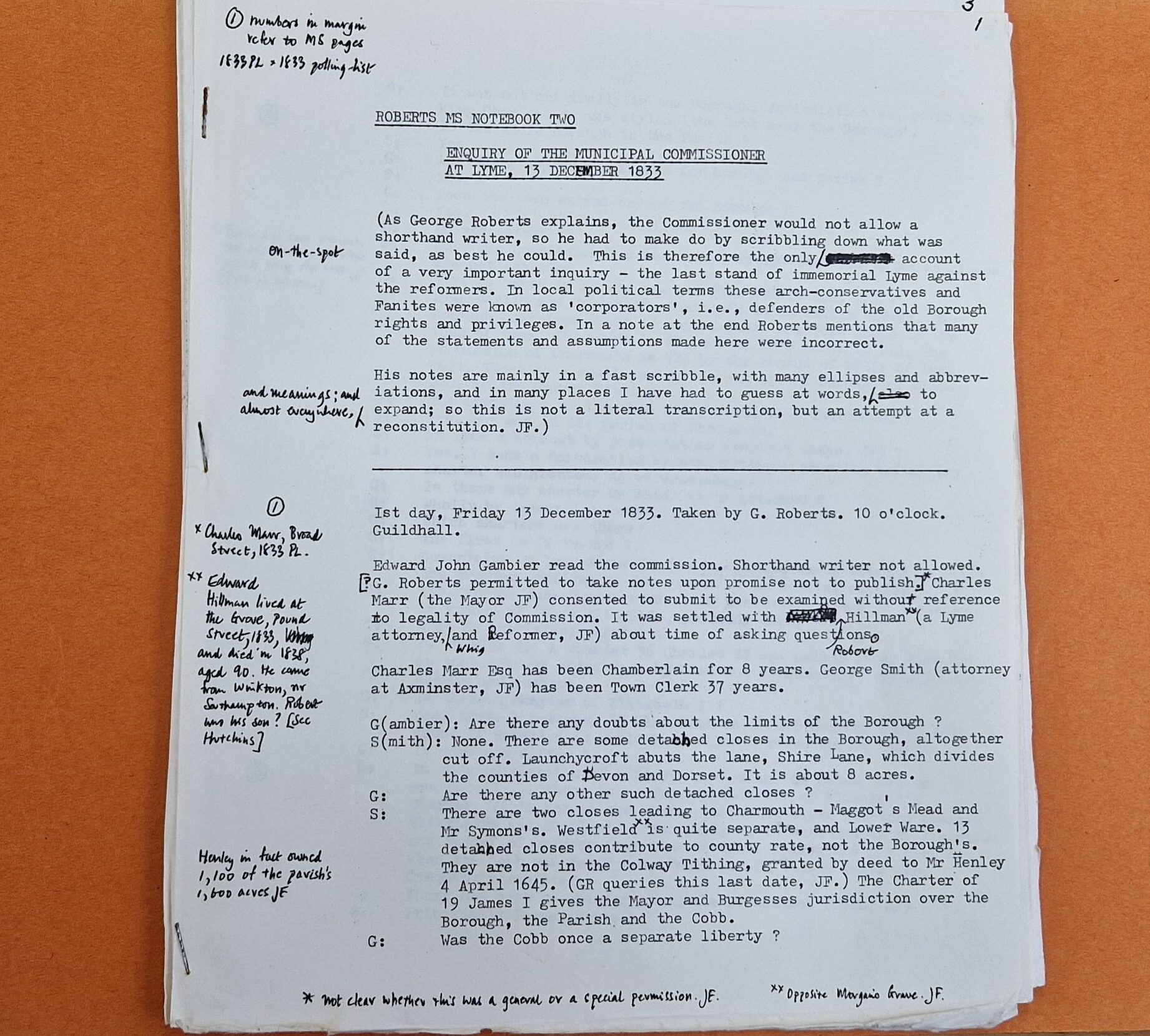

The antiquary and school teacher George Roberts was a notable archivist and historian of Lyme, where he was born and where he served as mayor. Naturally Fowles took a great interest in him and his publications about Lyme’s history, its landslips, the Monmouth Rebellion etc. The Collection contains a notebook of Roberts and also a copy of his Municipal Government of Lyme, whilst in a different box appears “Roberts notebook, annotated.”15

There is a file of notes and a reprint of Lyme Fifty Years Ago, first published in 189216. There is also a manuscript volume of Lyme history, dates and facts compiled by Fowles himself. Other papers apparently relating to the Museum and his work there are listed as “Notebook – Museum”, “Museum pending file: correspondence”, and “Miscellaneous Notes 1978-1988”. A further two files are described as “Very mixed files of assorted notes and correspondence”17. Although these may well be a goldmine of information please be reminded that the Fowles Collection is still uncatalogued, and probably largely unexamined and unsorted, and may be frustrating to consult!

The Lymiad, a previously unpublished Regency poem in the form of satirical letters, of which the manuscript is held in the Philpot Museum, was originally transcribed by John Fowles and he had written an introductory piece Lyme in the 1800s prior to his death in 2005. The Fowles Collection at the Dorset History Centre contains a file of his notes and correspondence relating to the work. It was finally published posthumously by the Museum in 2011, with a long general introduction by John Constable, under the joint editorship of Fowles and Constable. This seems a fitting item to close this blog and this series. Of course, much of the material held at Dorset History Centre remains unexamined, and awaits the interest of anyone keen to understand more about Fowles or Lyme Regis.

—

References:

https://archive-catalogue.dorsetcouncil.gov.uk/records/D-FWL [“D-FWL”]

Charles Drazin (ed.) 2006 John Fowles,The Journals Vol 2 [“Journals 2”]

Eileen Warburton 2004 John Fowles, A Life in Two Worlds [“Warburton”]

1 D-FWL, Box 4

2 D-FWL, Box 3

3 D-FWL, Box 5

4 Journals 2, 20 Nov 1988

5 D-FWL, Box 7

6 D-FWL, Box 6

7 D-FWL, Box 1

8 Journals 2, 28 May, 4 & 8 Jun 1977

9 Warburton p 430

10 D-FWL, Box 4

11 D-FWL, Box 7

12 D-FWL, Box 12

13 D-FWL, Box 10

14 D-FWL, Box 5

15 D-FWL, Box 9

16 D-FWL, Box 6

17 D-FWL, Box 11

—

Missed earlier posts in this series? You can read them here: