In our last Gypsy Romany and Traveller blog, we took a quick look at some of the problems you might encounter when beginning your research into any GRT ancestors. This time, our volunteer has taken a look at some of the problems when searching for people on the census…

—

One of the many advantages of visiting Dorset History Centre is being able to access the census returns for 1841 to 1911 using the computers in the Family History room. But if your ancestors were Itinerant Travellers, you may be frustrated to find that they don’t seem to appear in a census. This blog gives you some ideas as to why they might not appear and provides some background information on how information for the censuses was collected in the nineteenth century.

Within Dorset none of the census returns appear to have been lost or destroyed, but still errors crept in.

- Mishearing was likely if the household schedule was completed by the enumerator because there was no one literate in the household to complete the form – so many Ellens appear as Helen.

- Mis-transcribing was likely to be the result of the enumerator making an error when copying the information from the household schedules onto the enumerators schedules. It is only for the 1911 census that the household schedule is available to view. The vast majority of the earlier household schedules were destroyed.

- False information could be the result of deliberate action – so many times the ages of husbands and wives were given to narrow their difference in age. However, if no one was at home a neighbour might have been asked for the information and they may have just made a best guess, especially on ages and place of birth.

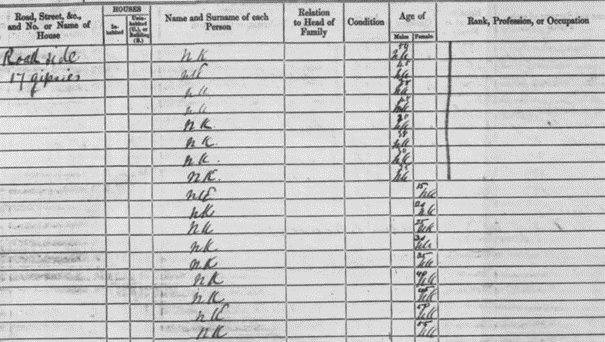

Another reason for not finding an ancestor on the census returns could be that the enumerator had explicit instructions not to include them. This is particularly important if you are looking for members of the travelling communities who were virtually invisible on the 1841 and 1851 census as enumerators were not specifically asked to enumerate those not living in ‘normal’ or permanent households – sheds, tents, caravans and the like – until the 1861 census.

A conscious effort was made to employ local men as enumerators in the hope that fewer errors would occur. However, many enumerators considered they were over-worked and underpaid for what was about a fortnight’s intensive work.

It is likely that an explanation was recorded for each established building if there was no completed household schedule- for example ‘building uninhabited’ or ‘occupants away’. But for tents and caravans and those who slept where they could, the completion of a household schedule becomes a lot more complicated. Where were families when the household schedules were handed out? Were they still there when the enumerator returned to collect the schedule? Did the enumerator even know that there was a temporary settlement on a roadside, in a field or on a common? Did they feel safe approaching a temporary settlement of strangers and insisting on collecting what was considered personal information?

An 1861 census enumerator in Kinson, Dorset seems to have tried their best, adding in what can only be approximate ages when all they knew was how many people and whether male or female.

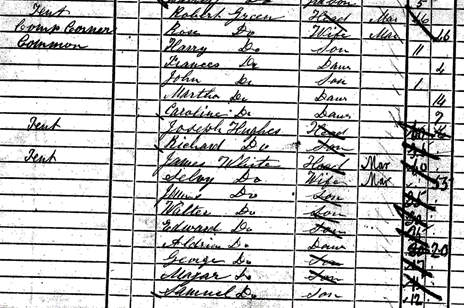

Ten years later for the 1871 census the enumerator for Redhill, Kinson managed to record names, relation to head of household and ages but not occupations or place of birth.

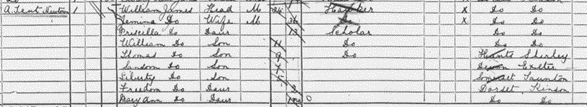

20 years later the 1891 enumerator has a completed schedule, but how much was down to co-operation from those living in the tents or the persuasive powers of the enumerator? Having the place of birth helps any family researcher find baptisms and understand the distances their family travelled and may even help distinguish between people with the same name.

—

Further reading:

www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/census-records/

Christian, Peter & Annal, David (2014) Census. The Family Historian’s Guide. London: Bloomsbury / TNA (2nd Edition)