As a researcher every so often you unfold an old and dirty parchment and go ‘wow’ as the potential importance of the document leaps off the page at you. But in some cases, before you rush to share your excitement with the archive staff, the gravitas and implications of the document demand a moment of respect and reflection which allows the document to be shared with the quiet solemnity and dignity due to those individuals named.

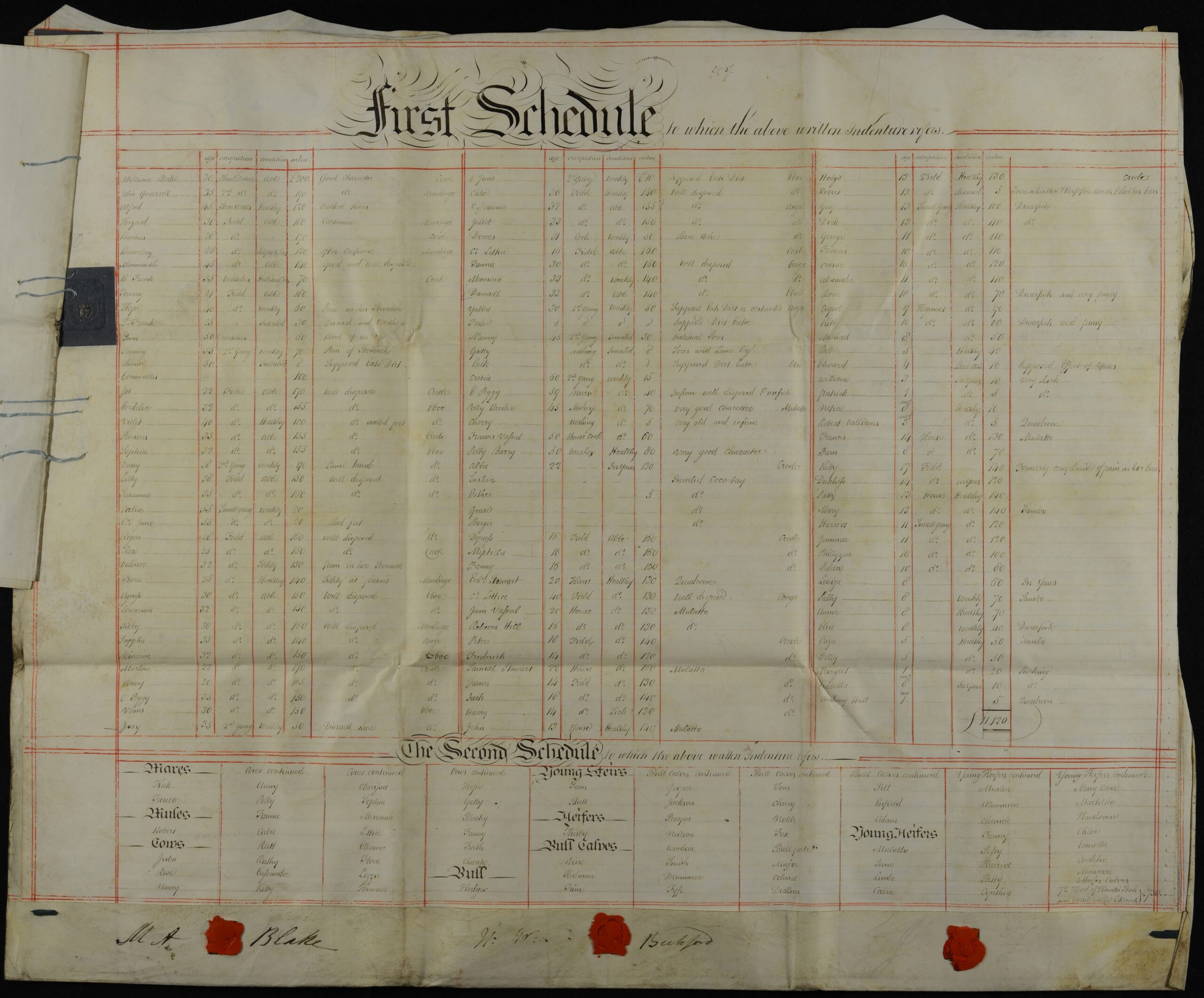

This was the range of emotions experienced when faced with a schedule accompanying the sale of the Mount Carmel plantation, Jamaica from Mary Ann BLAKE and Horace William BECKFORD in 1815. The schedule listed 115 enslaved individuals who formed the most valuable asset of the plantation. The plantation was valued at £10 653 16s 2¼d of lawful British money or £14 915 6s 8d Jamaican currency. This amount comprised:

Enslaved individuals £11 120 0s 0d

Stock (cattle and horses) £ 730 0s 0d

Land and buildings (402 acres) £ 3 065 6s 8d

Horace William BECKFORD, later the 3rd Baron Rivers, had three key connections with Dorset:

- His grandfather, Julines BECKFORD purchased land in Shillingstone and Steepleton Iwerne.

- Julines’ wife, Elizabeth ASHLEY, was the daughter of Solomon ASHLEY (MP for Bridport 1734-41). Solomon’s granddaughter, Mary, the wife of Humphrey STURT of the Critchel estate was Horace’s first cousin once removed.

- Horace’s mother was Louisa PITT. Louisa’s father, George 1st Baron Rivers, was returned as MP for Shaftsbury (1742-1747) and Dorset (1747-1774), serving as the Colonel of the Dorset Militia and the Lord Lieutenant of Dorset. Louisa’s brother, George 2nd Baron Rivers, was elected as MP for Dorset in 1774 and in about 1819 bought an estate at Tollard Royal.

The Mount Carmel plantation was combined with the Shrewsbury plantation which had passed through the BECKFORD family from Peter BECKFORD (Horace’s great grandfather) to Horace. All of this helps explain how a document now catalogued as D-PIT/T/855 is one of the many important historic documents held at Dorset History Centre.

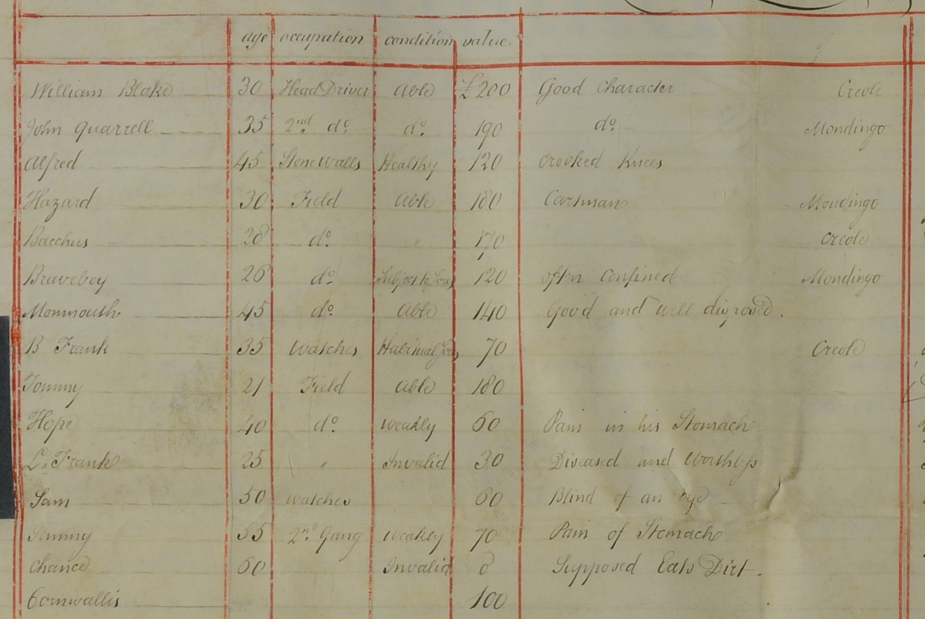

The schedule of enslaved individuals includes a name, age, occupation, condition, a value and some notes including ethnicity. It is this level of detail which makes the schedule more than just a list of names, giving a snap shot of who these individuals were and how the overseer and valuators viewed them.

Descriptions in the document also include:

- William Blake valued at £200, a 30-year-old head driver or supervisor, who was able, of good character and listed as ‘Creole’ (born in Jamaica and possibly of mixed heritage)

- Samuel Stewart valued at £160, a 22-year-old who worked in the house, who was healthy and listed as ‘mulatto’ (first generation mixed race)

- Polly Brodie valued at £80, a 45-year-old midwife, who was ‘weakly’, of very good character and ‘mulatto’ (first generation mixed race)

- Robert Williams valued at £5 a healthy 3-month-old listed as ‘Quadroon’ (3 white and 1 black grandparent)

- Beck with no value or occupation, an invalid, ‘supposed dirt eater’ and Eboe (from the southeast of Nigeria, a first generation slave)

It should be noted that the names of enslaved individuals as recorded can be original or ascribed by an ‘owner’ or merchant.

The table below gives a breakdown of the ascribed ethnicities, at a time of multiple and complex systems of categorising race. Only 60 (52%) of the entries have a relevant entry:

| Ethnicity | Number | % |

| Creole (born in Jamaica) | 20 | 17 |

| Congo (from the Congo area of central Africa – today the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo – first generation enslaved) | 8 | 7 |

| Eboe (from the southeast of Nigeria – first generation enslaved) | 15 | 13 |

| Mondengo (from or near the upper Niger valley, Western Africa – first generation enslaved) | 5 | 4 |

| Mulatto (first generation mixed race) | 6 | 5 |

| Quadroon (3 white and 1 black grandparent) | 3 | 3 |

| Sambo (3 black and 1 white grandparent) | 3 | 3 |

It is reasonable to assume that the total born in Jamaica should include the 12 (11%) mixed race individuals giving a total for Creole of 32 (28%).

Part 2 of this blog will be published on Monday, and will use documents not held by DHC to show how research into families and individuals can be developed from these starting points.

This is a great and valuable piece of research.