The history of Tyneham in the present tends to focus on its military turning point during the Second World War, when the villagers were evacuated in December 1943 by the military and were not allowed to return post-war. Even now, councils and associations as far as Portsmouth are in deliberations about how to restore the once warm countryside village to an area that has become so famous for its wartime past. However, the story of Tyneham stretches back centuries before this and is rich in a history that is often pushed aside by social historians. One history is that of the apprentices that emerged after The Poor Relief Act 1601, more commonly known as ‘The Poor Laws.’

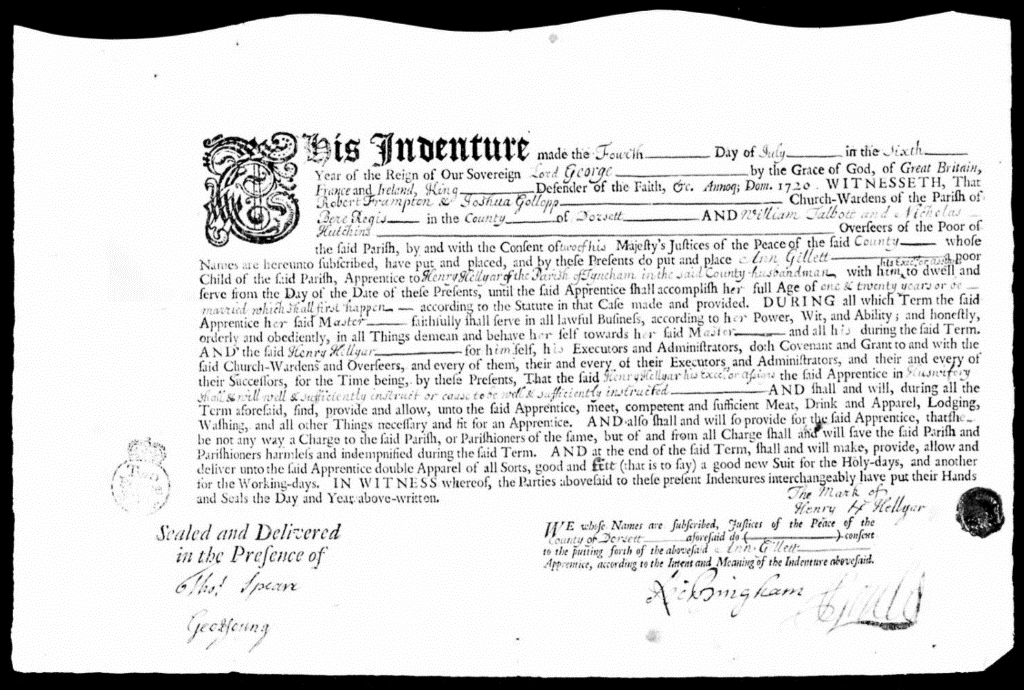

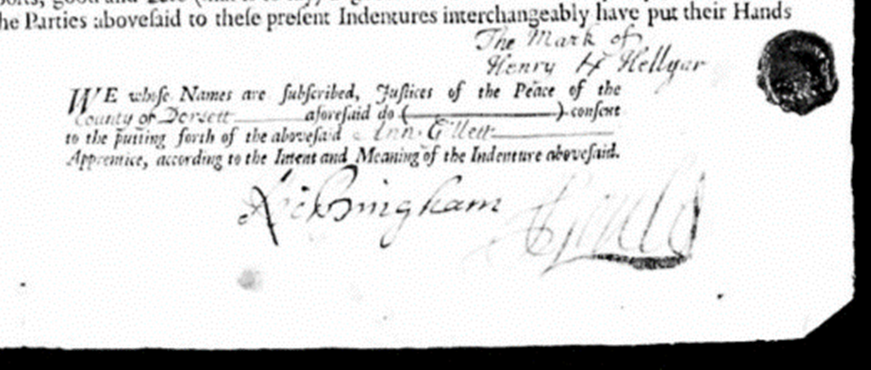

Let us introduce you to Ann Gillett, a girl born on 15th May 1707 in the civil parish of Bere Regis. Daughter to Thomas Gillett and sibling of John and Thomas Gillett, Ann was the eldest child. Thomas Snr was not married as far as we can discover through extensive research of ancestral documents, but the evidence of the four of them being a poor family is that all of Thomas’ children received indentures into apprenticeships across the county. At the age of thirteen, on 4th July 1720, Ann was sent to Tyneham to her new master Henry Hellyar, whereby she would become an apprentice in husbandry until she turned twenty-one or she married. At this time women may have been more motivated to marry in order to have their own household, benefit from a double income or perhaps to leave an apprenticeship, however the start of married life also meant, for many, the beginning of a long series of risk-laden pregnancies.

‘Leave clauses’ tended to vary per case of indenture, all three of the Gillett children had different clauses. John could leave his master once he turned twenty-two and Thomas at twenty-four.

Ann worked in animal husbandry during her time in Tyneham. A much later document held at Dorset History Centre, ‘Animal Husbandry’ by John Bankes V, written as part of his studies in 1955, provides us with detailed notes about the profession and how to appropriately care for young livestock and bird flocks. Such activities would have been part of Ann’s daily life, learning how to rear the young and bring them up for either further reproduction, production of beef or milk.

Ensuring animals did not contract diseases was also important in husbandry but at a lot of the illnesses Bankes speaks of were not yet discovered in Ann’s time. The only probable illness they were aware of in the 1720s was Hand, Foot and Mouth which was first noted in cattle in the 1500s.

—

Apprenticeships in husbandry and agriculture were a common practice in the 17th through to the 19th centuries, due to the nature of husbandry being a continuous task it was useful to have year-round workers. There were, of course, also apprenticeships in other fields ranging from baking and tailoring to making mops, after all, someone had to! For some context, in rural areas around 60% of people between the ages of 15-24 were ‘servants’, a term which encompassed apprentices.

Young apprentices were often hired to fill a gap in the family where a teenager would have contributed. As well as this, a comparatively high age of marriage and having children meant a risk of parents dying before their children reached adulthood ruining the family economy, and it also meant there were many orphaned teenagers that were potential farm servants.

Teenagers filled this role because that is when they became economically useful, any younger and they could not work effectively. While apprenticed, they would be fed and housed, and that also meant that burden was not on their parents during that time, in addition to what they would be paid.

This is not to suggest that the apprenticeships of farm servants were a perfect arrangement, the motivation of the servants was doubted, cautioning against the hiring of lazy people, potential thieves, or even ones who were “…addicted to company-keeping…”. Servants could also be ‘fired’, for reasons such as drunkenness, pregnancy, or just incompetence. It seems to be a common sentiment that servants required near constant observation, and they generally worked long hours including unsocial ones. According to Donald Woodward’s article, Early Modern Servants in Husbandry Revisited, they could even be working on Sundays, and Christmas Day!

—

Why did agriculture and husbandry apprenticeships phase out? There were a couple of important factors, the longer-term reason being increased investment in agriculture, essentially, bigger farms that needed more workers. This made servants who would stay and integrate with the family less cost effective in comparison to hired seasonal workers, that didn’t need to be housed.

There were also the Napoleonic Wars; thanks to warfare on the seas, importing grain became much more difficult and so prices dramatically increased. This meant many farmers, who weren’t growing grain, were suddenly much poorer themselves, and many switched to grain over livestock which was seasonal work.

You can see a parallel to be drawn here with the past and present, in the age of zero-hour contracts it’s easy to draw a similarity in the desire for economic efficiency in hiring seasonal laborers over year-round ones.

In the next blog Ben will introduce you to another apprenticeship story from the collections.

—

Further Reading:

Bankes, John. Animal Husbandry. Self-published – Available at Dorset History Centre. 1955 (D-BKL/H/S/2/38)

Kussmaul, Ann S. “Servants in Husbandry in Early Modern England.” The Journal of Economic History 39, no. 1 (1979): 329–31.

Wallist, Patrick. “Apprenticeship and Training in Premodern England.” The Journal of Economic History 68, no.3 (2008): 832-61

Cunningham, Hugh. “The Employment and Unemployment of Children in England c.1680-1851.” Past & Present, no. 126 (1990): 115–50.

Kussmaul, Ann S. “Servants in Husbandry in Early Modern England.” The Journal of Economic History 39, no. 1 (1979): 329–31.

Woodward, Donald. “Early Modern Servants in Husbandry Revisited.” The Agricultural History Review 48, no. 2 (2000): 141–50.

—

This has been a guest blog written by Molly Butcher and Ben Corben-Hale, who spent four weeks at Dorset History Centre doing work experience. If you would like to contribute a guest blog for publication, please get in touch: archives@dorsetcouncil.gov.uk