On Friday we published a blog detailing the information from one document held at Dorset History Centre. This blog will explore further the history of enslaved individuals in Jamaica and will show how research can be developed using online resources.

—

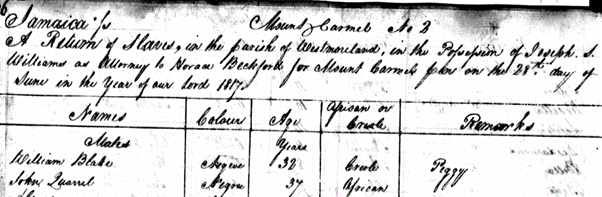

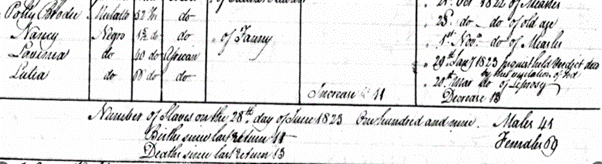

In 1817, two years after the sale of Mount Carmel, Jamaica finally complied with the 1815 Bill requiring the registration of slaves. This was an attempt to ensure that the 1807 Abolition of Slavery Act was adhered to. Using access to Ancestry.co.uk in the Family Search room at DHC the 1817, 1823 and 1829 returns for Mount Carmel plantation (originals at The National Archives, Kew) were viewed. On the 1817 return 14 of the enslaved individuals on the schedule (D-PIT/T/855) cannot be identified. For the identified 101, the table below gives a breakdown of the information given in addition to name and age.

| Number | |

| Colour (ethnicity)

Mulatto Negro Sambo Quadroon |

101

3 89 8 1 |

| African (1st generation enslaved) | 41 |

| Creole (born in Jamaica) | 60 |

| Remark (Mother’s name) | 51 |

Subsequent Returns of Slaves for Mount Carmel, 1823 and 1829, only listed changes to the original registration, but from this we learn of 11 deaths. In all but one the cause of death was given and for Lavinia’s death, 29 January 1823, an inquest was held with the verdict “died by the visitation of God”.

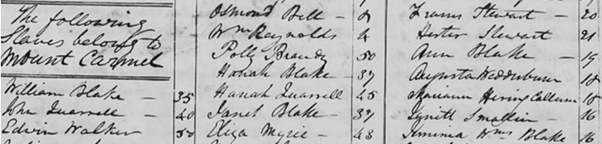

In 1819 Edmund Pope, Rector of the parish of Westmoreland, Jamaica, undertook a mass baptism of “slaves belonging to Mount Carmel”. Of the 101 individuals 38 were male and 63 female – very much what would be expected from the 1817 return. However, only 8 could be conclusively and 22 possibly linked to the schedule. Even this was only possible because this was one of the rare occasions that the Rector recorded the ages, rather than just the baptismal names, which were most likely not the names the individuals had been recorded with previously. Researchers acknowledge that it is difficult to know if a recorded name was the enslaved person’s chosen name, one imposed by their owners or how a baptismal name was selected. To date no other mention of any of these individuals has been identified within the church registers for Westmoreland, with no marriages or burials of enslaved people appearing to be recorded in the church registers (which can be viewed on Family Search).

—

The following case study was created by combining all the information found.

Polly BRODIE was a ‘Mulatto’ born about 1770 in Jamaica. She worked as midwife and was of very good character, but in 1815 her condition was weakly. The 1823 Return of Slaves recorded that Polly died of old age on 23 October 1822. Polly had at least five children all born in Jamaica:

- William Seal aka Cornwallis – born about 1787; only had his value recorded in 1815 and was described as ‘Quadroon’ in 1817.

- Samuel STEWART – born about 1793

- Eleanor STEWART – born about 1795; had at least one daughter, Mary REYNOLDS, a ‘Quadroon’ who died of measles 21 October 1822 aged 11 months and a son who was born 17 June 1828.

- Francis STEWART – born about 1801; had at least one daughter – Jennett, a ‘Quadroon’, born 10 May 1822 and a son, John, born 24 September 1827.

- John STEWART – born about 1802

Although the four youngest were described as Sambo in 1817, in 1815 the three boys had been recorded as Mulatto and Eleanor as Quadroon. The four youngest children worked in the house and, in 1815, were healthy.

The racial identities ascribed to the various members of the family can be illuminated by the views found in the Journal of Lady Maria NUGENT, the wife of the Governor of Jamaica. In 1802 she wrote:

“if our white men would but set them a little better example. . .they [Negroes] would. . . render the necessity of the Slave Trade out of the question, provided their masters were attentive to their morals, and established matrimony among them; but white men of all descriptions, married or single, live in a state of licentiousness with their female slaves”

No matter how abhorrent a list of enslaved people may be, given the absence of recording of the key life events such as baptisms, marriages and burials for most enslaved people these schedules need to be respected, and the names listed spoken. They may be the only record giving a name to those who otherwise would just be recorded as an anonymous group of enslaved individuals.

—

SOURCES:

DHC resources – D-PIT/T/355

Jamaican Family Search Genealogy. www.jamaicanfamilysearch.com

Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery. www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/

Family Search – Jamaican church records. www.familysearch.org

Ancestry.co.uk – The National Archives: Office of Registry of Colonial Slaves Records, 1819-1848 (ref: T 71) www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/1129/