In January 2024 Dorset History Centre will be undertaking two collections weeks and we will be closed to the public for this period.

Whilst staff and volunteers will be getting on with the important work we have to do during this period, we have this two-part guest blog for our readers, from Martin Gething…

—

James Frampton (1769-1855), the squire and Lord of the Manor at Moreton, Dorset, is notorious for being the landowner who sent the Tolpuddle Martyrs to court in 1834. What is not so well known, though, is that James Frampton found himself ‘in the dock’ in 1843.

A farm track, or a Public Highway?

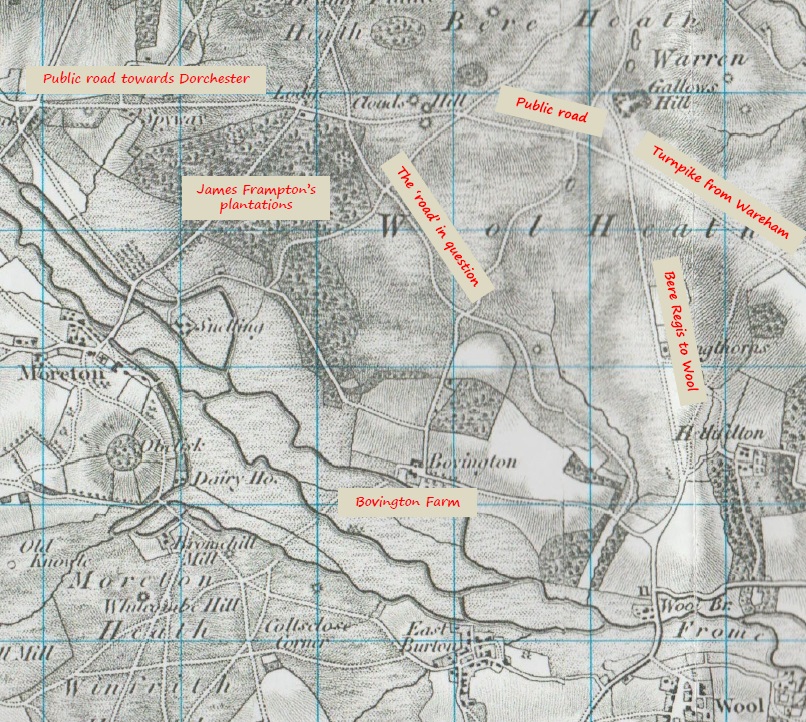

It concerned a farm track across a part of Wool Heath that Frampton owned. There was a Turnpike road – now called Puddletown Road – from Wareham to near Clouds Hill, which had been extended westwards as a public road towards Tincleton and Dorchester. From Clouds Hill there was a path heading south across the heath, that connected the public road with Bovington Farm.

James Kellaway, a labourer on Bovington Farm (which was not part of Frampton’s property), was not happy with the state of the path, and, egged on by an attorney based in Wool named John Carter, brought a complaint against Frampton that he was ‘not maintaining the public highway’. Frampton rejected the claim on the basis that it was nothing more than a farm track for the convenience of his tenants and himself, and had never been a public road.

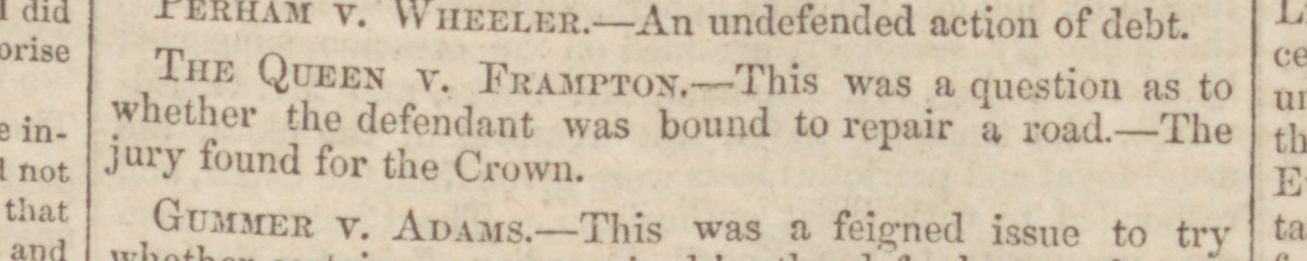

John Carter lodged a similar complaint on behalf of the residents of Wool, and the two cases became Carter v. Frampton and Kellaway v. Frampton. However, common law defines a Highway as ‘a way over which there exists a public right of passage, that is to say a right for all the King’s [Queen’s] subjects to pass and repass without let or hindrance’, and so the two were combined as Queen v. James Frampton Esquire and brought to the Dorset Assizes in 1843.

Dorset Summer Assizes, July 1843

As part of the evidence presented on behalf of James Frampton – it is unlikely he attended the hearing himself in person – it was stated that there were “various tracks across this Heath […] have been made at different times by the neighbouring people with Waggons and Carts in fetching Timber from the adjoining Woods of the Framptons, or in the carriage of Turf which is cut and sold to them from the Heath in the Autumn, and is the principal source from whence they derive their fuel during the Winter Months. They are also traversed by the tenant of Bovington Farm for his private convenience, but it has never been considered as any Road for the purposes of the Public.”

To support his claim, Mr Frampton called on various tenants to give evidence that the track had always been boggy and rutted, and hence was not suitable for general use, and that they had directed anyone going to Bovington to go eastwards to Gallows Hill and then south along the road from Bere Regis.

Nevertheless, James Frampton lost the case.

The court imposed a fine of 6 shillings and 8 pence and ordered Frampton to repair the road (which must surely have cost much more than the fine!).

1844 – Road repaired

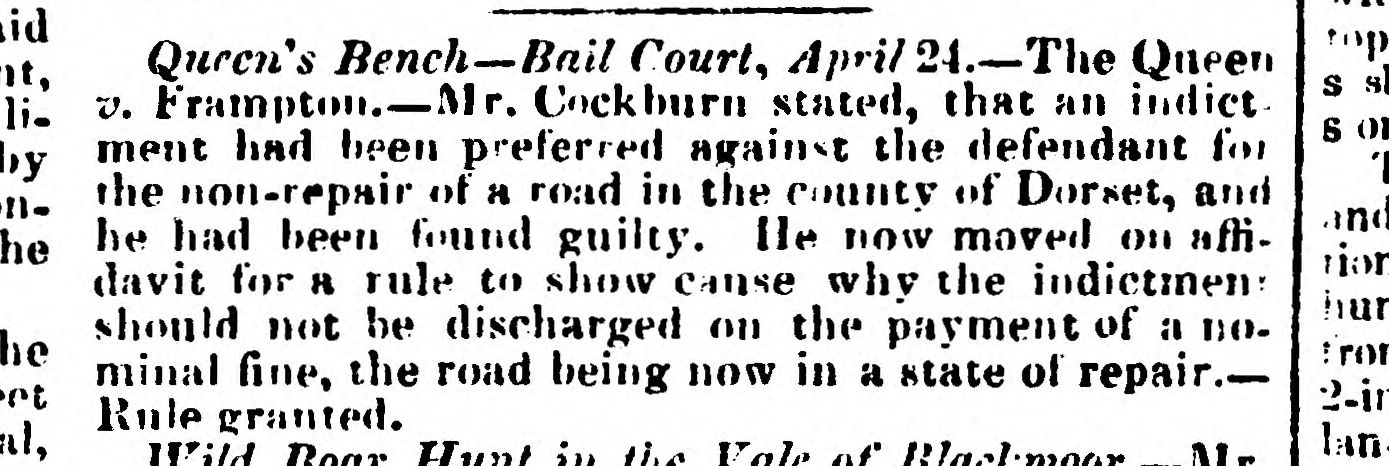

The following year two certificates signed by magistrates and an affidavit signed by a bailiff were presented on behalf of James Frampton on 24 April 1844, stating that the road was now in a good state of repair, and a ruling was obtained that he could be discharged from the indictment, having paid the 6s 8d fine.

Formally, it was a Rule nisi (‘unless’): namely that the case would be considered discharged unless the prosecution could “provide satisfactory evidence or argument that the decree [Rule] should not take effect” (Wikipedia).

—

In part two of this blog (which will be released on Friday), Martin will explore what happened next for Frampton and the law…