Between 2015 and 2018 Dorset History Centre undertook the ‘Unlocking the Bankes archive‘ project. During the life of this project, staff and volunteers contributed well over 100 blogs to the project website. As we reach 2024, this project website is no longer functional in the way it originally was, and we have made the decision to close the website permanently.

However, we didn’t want to lose all of the intriguing stories and individual research which had been done by so many people, and we are therefore going to slowly be recycling these pieces onto this blog site going forward, to ensure that these fascinating tales have a home for people to read (or possibly re-read)!

We start off this recycling process with a curious discovery by William John Bankes…

—

It is difficult to imagine the stir which was caused in 1850 when London Zoo received a gift of a male 37 stone hippopotamus called Obaysh. He was the first hippo to have been seen in Europe since the days of the Roman Empire and he attracted up to 10,000 visitors a day. It is hardly surprising then, that 33 years earlier William John Bankes was equally excited when he came across a hippopotamus which he could study at close quarters. However, this was not a live hippo, but one which had recently been killed.

In 1817 Bankes was travelling in Egypt meticulously recording ancient temples and tombs and carrying out his pioneering work on Egyptian hieroglyphs. His insatiable curiosity extended to everything he encountered on his journeys, including the differing tribes-people and the unusual plants and wildlife.

Hippopotamuses were known to live in the upper reaches of the Nile, beyond the second cataract towards Nubia, where at this time only a handful of Europeans had ventured. This hippo, however, had been only a few miles from the Mediterranean, in the very lower reaches of the Nile delta.

In his own notes Bankes records:

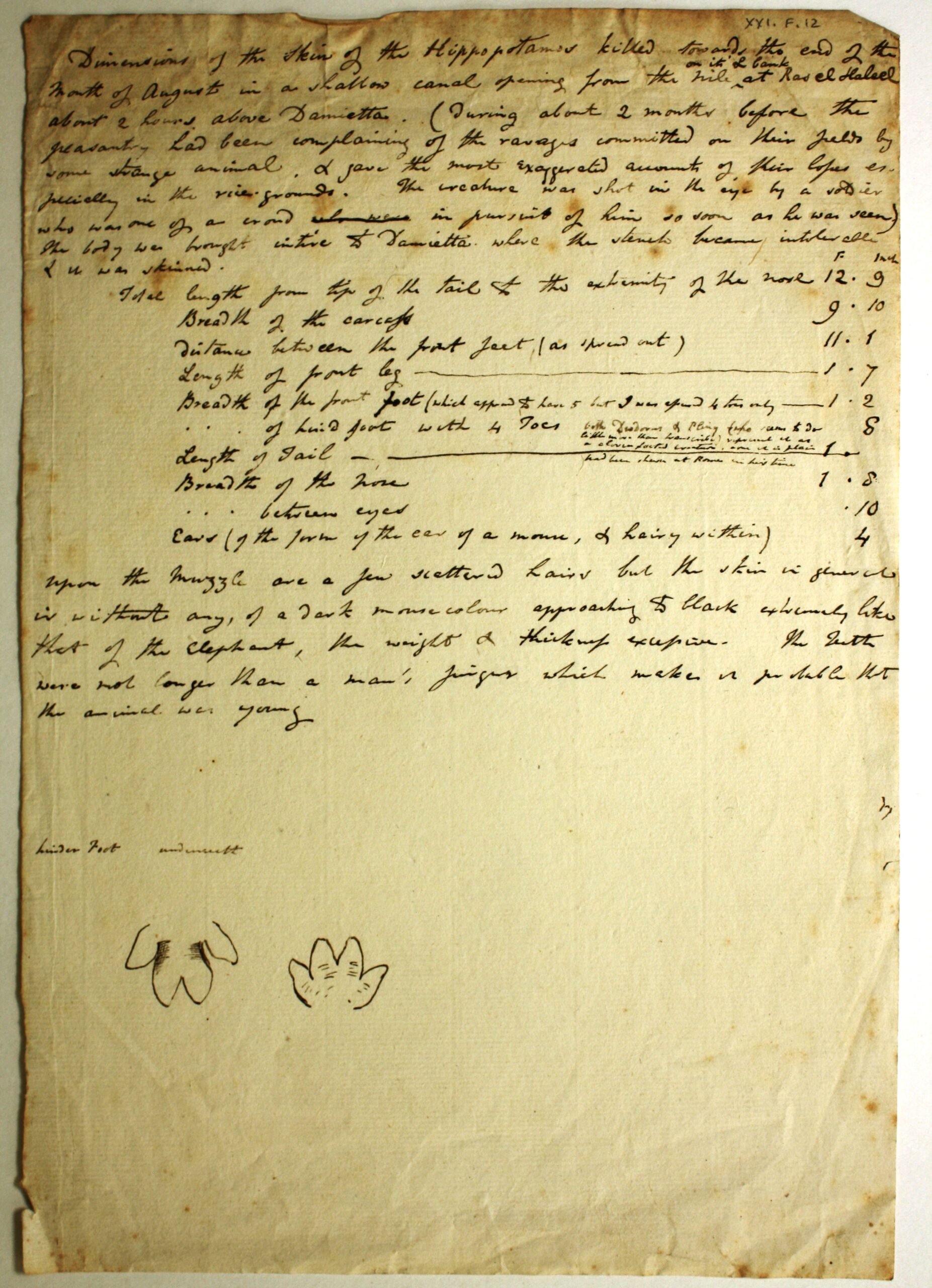

During about two months before, the peasantry had been complaining of the ravages committed on their fields by some strange animal .. The creature was shot in the eye by a soldier who was one of a crowd in pursuit of him so soon as he was seen. The body was brought intire to Damietta where the stench became intolerable and he was skinned.

William then takes detailed measurements, as he was used to doing when discovering a temple:

‘Total length from top of the tail to the extremity of the nose – 12ft 9in

Breadth of carriage – 9ft 10in

Distance between the front feet (as spread out) – 11ft 1in

Length of front leg – 1ft 7in

Breadth of the front foot (which appeared to have 5 but I was offered 4 toes only) – 1ft 2in

Breadth of hind foot with 4 toes – 8in

Length of tail – 1ft

Breadth of the nose – 1ft 8in

Breadth between eyes – 10in

Ears (of the form of the ear of a mouse, and hairy within) – 4in

Upon the muzzle are a few scattered hairs but the skin in general is without any, of a dark mouse colour approaching to black, extremely like that of the elephant, the weight and thickness exceptive. The teeth were not longer than a man’s finger which makes it probable that the animal was young.’

Bankes adds a critical note beside the foot measurement ‘Both Deodorus and Pliny (who seem to do little more than transcribe) represent it as a cloven footed creature. None it is plain had been shown at Rome in his time’. At the foot of the page he draws a sketch of the hind foot to back up his discovery.

William explained in a later letter to his father (D-BKL/H/H/4/59) just how extraordinary his find was:

‘We are so accustomed to associate the idea of the hippo with the Nile, that I believe there are a great many in England who would suppose that the sight of one would be no more a rarity to a traveller in Egypt than that of a jerboa or a crocodile. It is however so far otherwise, that there is no well attested account of another having been seen below the cataracts within the memory of man, in fact the modern Egyptians have no name for it, and the last time I was in this country I remember to have heard even its very existence in the river questioned by previous residents here.’

200 years later, amateur zoologists no longer need to measure putrid animal skins – they can just sit back and watch ‘Planet Earth’!

Author: Fiona Wake-Walker