Between 2015 and 2018 Dorset History Centre undertook the ‘Unlocking the Bankes archive‘ project. During the life of this project, staff and volunteers contributed well over 100 blogs to the project website. As we reach 2024, this project website is no longer functional in the way it originally was, and we have made the decision to close the website permanently.

However, we didn’t want to lose all of the intriguing stories and individual research which had been done by so many people, and we are therefore going to slowly be recycling these pieces onto this blog site going forward, to ensure that these fascinating tales have a home for people to read (or possibly re-read)!

This time we have the thoughts of Henry Bankes about the summer weather in 1817…

—

In recent years we have experienced exceptionally hot summers. With temperatures rising to well over 30 degrees Celsius, everyone’s had something to say about the heat.

As did Henry Bankes II. In June 1817, he wrote in his diary: a ‘week of uncommonly hot weather’. You might be thinking, “So what? That’s normal for June isn’t it?”

But the point is that in 1817, the weather had not been “normal” for two years.

Why?

In April 1815, Mount Tambora erupted in Indonesia. The cloud of ash was so large, it blocked out sunlight and affected global weather conditions for the next three years. It caused famine, disease and unrest around the world. The eruption was labelled as one of the “largest eruptions of the last 10,000 years” and caused an estimated 100,000 deaths in the local area.

1816 became known as “the year without a summer”. Many states across America saw snow and frost in June; rice crops failed in China; and in Ireland it rained for eight weeks straight. Indeed, it was this bad weather that inspired Mary Shelley to write Frankenstein whilst on holiday in Switzerland.

In the diaries…

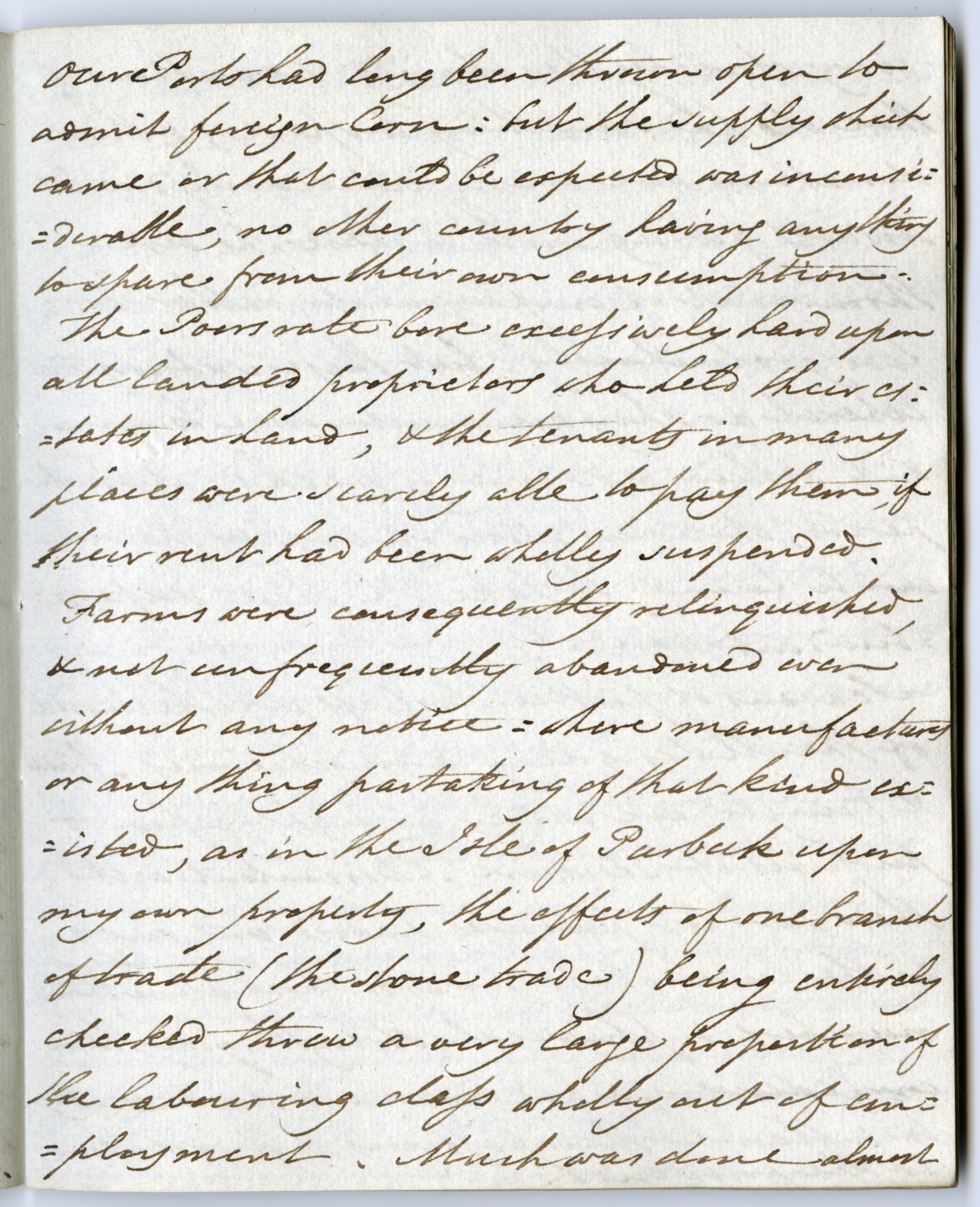

Henry Bankes writes in his diaries (D-BKL/H/H/1/98):

‘September 1816: a general calamity …extended over the whole continent of Europe, as well as of America, of most unseasonable weather and a deficient harvest….’

He goes on to say:

‘The grievous effects of the unfavourable harvest were felt throughout the kingdom as heavily as elsewhere. I never remember so long a continuance of wet weather during the whole summer and autumn, which delayed everywhere the carrying in of crops, prevented the corn coming to maturity, and in many counties rendered it unfit for the food of man.’

The knock-on effects of these failed harvests were disastrous.

‘Farms were… relinquished and… abandoned even without any notice.’

‘… in the Isle of Purbeck, upon my own property… the stone trade…threw a very large proportion of the labouring class wholly out of employment.’

It could be argued that 1817 was one of the grimmest years in British history. Looking through Henry’s diaries, we can see the rioting and unrest:

- January – There is an ‘assassination attempt’ on the Prince Regent on the way from Westminster

- March – Textile workers demonstrated in Manchester

- June – An armed uprising known as The Pentrich Rising took place in Derbyshire

- November and December – The trial of the rioters from The Spa Field Riots occurred in Islington

No wonder that Henry (an active M.P. for Corfe Castle) was alarmed. Hunger and distress could lead to “disturbances”, even to revolution. After all, that’s what had happened in France in 1789, wasn’t it?

‘Discontent with their own lot produces hatred and envy in the lower class towards those above them.’

“Gagging Acts” were quickly passed by March, restricting public meetings and publications. The suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act followed; suspects were imprisoned without trial. 26,000 troops were deployed around the country to maintain order.

What Happened Next?

Better harvests in 1817 & 1818 relieved hunger & distress. Repression succeeded; threats of revolution receded. But not entirely. In 1819 there was the Peterloo massacre, and by the 1820s there were rebellions and uprisings in towns and cities across the country. This fragile tinder-box had been exposed to a spark from a volcano’s eruption in Indonesia.

Author: Roger Lane