February marks LGBTQ+ history month. Our new Principal Archivist Claire has taken some time to reflect on gender representation in historic archives…

—

I have always felt a bit wary of the idea of having separate months for particular communities because of the implication that community is only entitled to be remembered one month out of the year, but of course that’s not the aim! The aim is to remind all of us that people who have traditionally been less visible in society both exist and have a rich history.

One of the projects I found particularly inspiring when I worked in Plymouth was Gendering the Museum: https://genderingthemuseum.co.uk/ a project led by Professor James Daybell of the University of Plymouth. The project has created a toolkit which assists heritage organisations “to uncover the hidden resonances of items relating to gender and sexuality, and … to counter the narrative that gender diversity is a new invention.”

Medicine is one area mentioned by the toolkit where you can uncover changing attitudes to gender, interesting to anyone interested in gender fluidity. The case studies in the toolkit include references to “antimony” which was a poison used as a medicine to help regulate the perceived “instability” of women, linked to an early medical theory of the “Four Humours.” Men were characterised by being “hotter and dryer” than women, and therefore better at controlling their emotions and bodily impulses. These kinds of misogynistic gender assumptions reverberate down the centuries. “Big boys don’t cry” continues to be said by some people, even in the 21st century, but we know that the opposite is true; that bottling up emotions can be damaging to mental health and that crying is cathartic and helps remove toxins from the body.

Using the examples in the toolkit as an inspiration, I have done some digging in the archives at Dorset History Centre, trying to think laterally and using “medicine” as a search term to uncover items of interest for the history of gender identity.

—

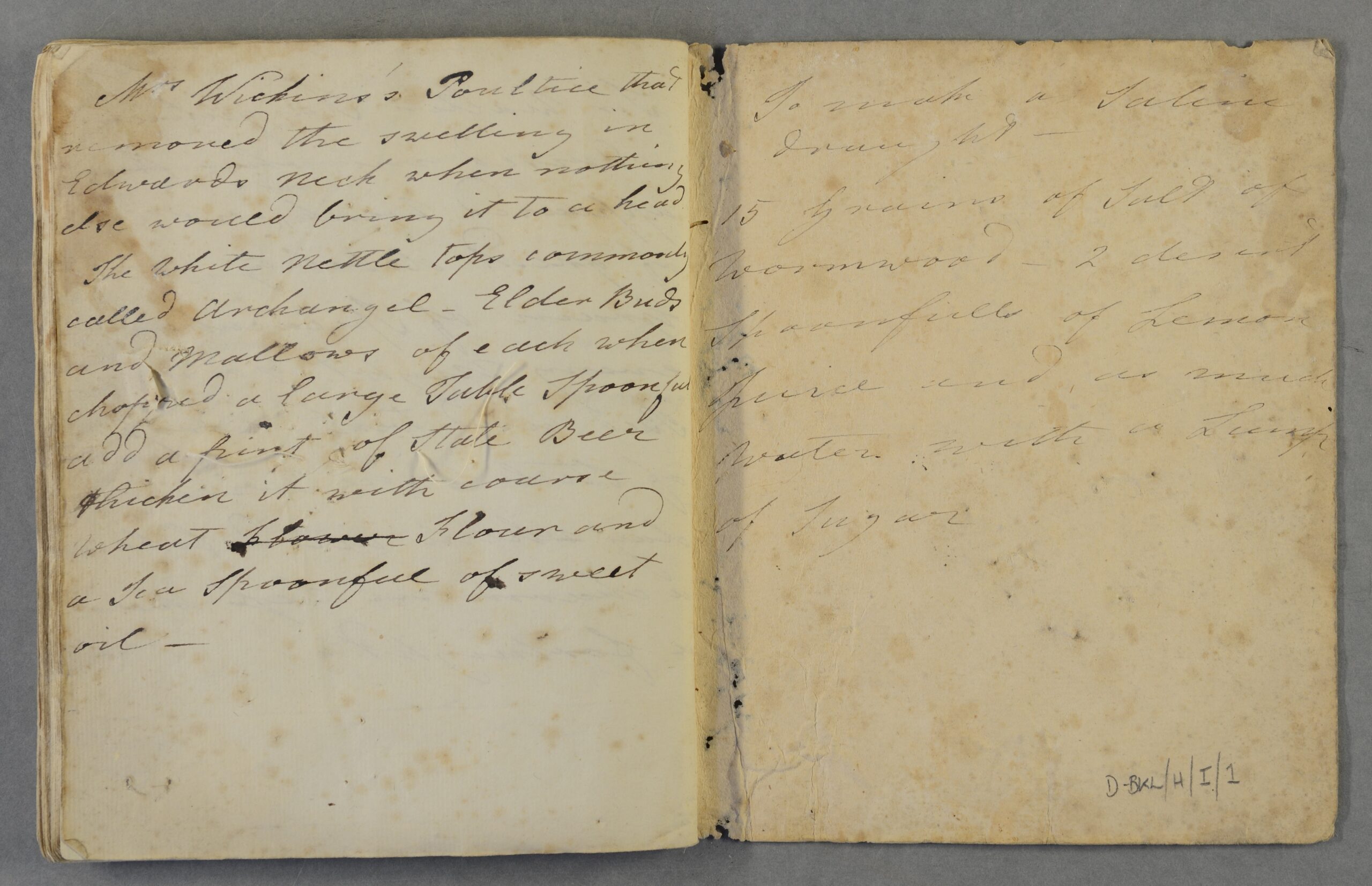

I found a fascinating record, D-BKL/H/I/1, which is a notebook kept by Frances Bankes between 1786 and 1802 in which she describes the medical treatment used for her children. Most of the ailments are not gender specific but then on page 66 is a description of a: “[t]reatment for girls aged between twelve and fifteen.”

“She should eat but little fruit or Vegetables, no acids upon any account, ride on Horseback and wear worsted stockings, take great care not to wet her feet, and whenever she looks or feels a little unwell she should take a Tea spoonful every morning of the Elixer Profiretates [or Proseritates?] which I took myself for near two years. Upon uncommon pains in the stomach a Tablespoonful of Hierapicra may be taken but it is not so safe a medicine as the other. Fifteen drops of the Elixer of Vitriol to be taken in Tea made of Red Roses. For Nervous complaints Mrs Bankes14 Camphire Jellys.”

“Worsted stockings” were fine woollen stockings.

“Elixer Profiretates” I have been unable to translate – but clearly some kind of medical tonic in liquid form.

“Hieraprica” is “a warming cathartic medicine, made of aloes and canella bark.”

(Canella bark is derived from a West Indian tree, and resembles cinnamon.)

Source: https://www.thefreedictionary.com/Hierapicra

“Elixir of Vitriol” is a “mixture of sulphuric acid, alcohol, and aromatics (usually ginger and cinnamon). Whatever the preparation, this elixir was prescribed as a tonic and for stomach disorders.” Source: https://lewis-clark.org/sciences/medicine/chemical-drugs/

“Camphire Jellys [possibly Jelip]” – I believe “Camphire” is camphor, and camphor oil is still used today in aromatherapy to reduce anxiety. (It is not recommended for pregnant women however.)

To see that girls going through puberty in the late 18th century were being encouraged to go horse-riding but not to eat fruit or vegetables is fascinating! We are so used to being told to eat our “five a day!” It is also interesting to see the range of medicines regarded as essential for a teenaged girl’s wellbeing. It is tempting to think that “uncommon pains in the stomach” might refer to menstrual cramps – but of course there is no definitive proof of this. Menstruation was a topic which was taboo for centuries and there were no commercial products to assist with it in the UK until the mid 19th century. According to some online sources, red rose tea is still used today to help with PMS and anxiety as well as reducing bloating and alleviating cramps, so this does lend support to these remedies being aimed at dealing with the side-effects of menstruation.

It takes time and perseverance to find these “gendered” stories. Yet it can be incredibly rewarding to have these more personal insights into how our ancestors lived and how attitudes to gender and sexuality have changed over time.

Have you uncovered any hidden stories like this from the archives? Do let us know in the comments below.