Talk to any bookbinder or book conservator about their favourite parts of a binding and the likelihood is that endbands will be pretty high up on the list. Found at the top (headband) and bottom (tailband) of the spine, endbands have both structural and decorative features and are extremely enjoyable to make.

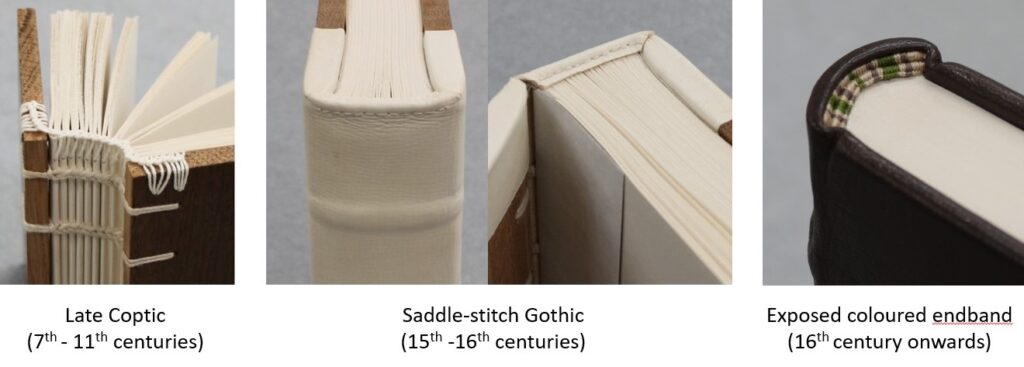

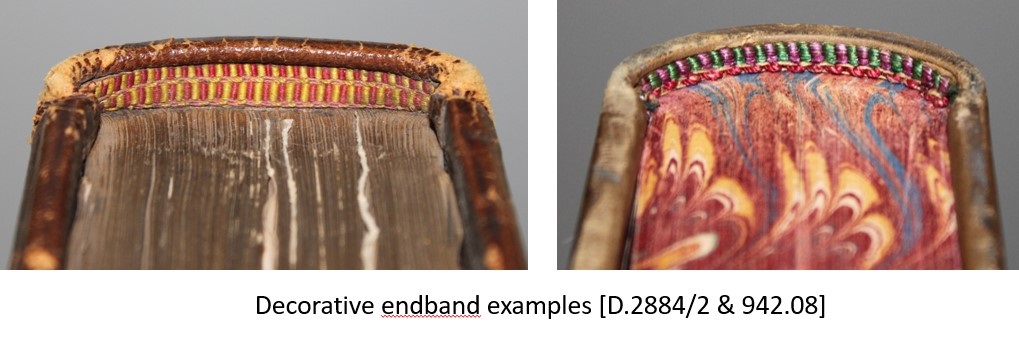

In Medieval times, when the first books as we now recognise them were being constructed, endbands were part of the sewing, extending across the spine of the text-block (the pages of the book) and incorporated into the boards, providing structural support to the binding. As time progressed they evolved, consisting predominantly of a core made from vellum, leather, catgut, rolled paper or cord, and wrapped or woven with silk or linen thread. In the 15th century the core was laced into the boards and leather was wrapped over the top of the endband and sewn through, making them invisible. From the early 16th century, the leather was formed into a ‘headcap’ over the endbands, leaving them exposed and providing a decorative feature of the binding. Later, the core of the endbands were cut off in line with the text-block and were no longer laced into the boards. At this point they became more decorative than structural.

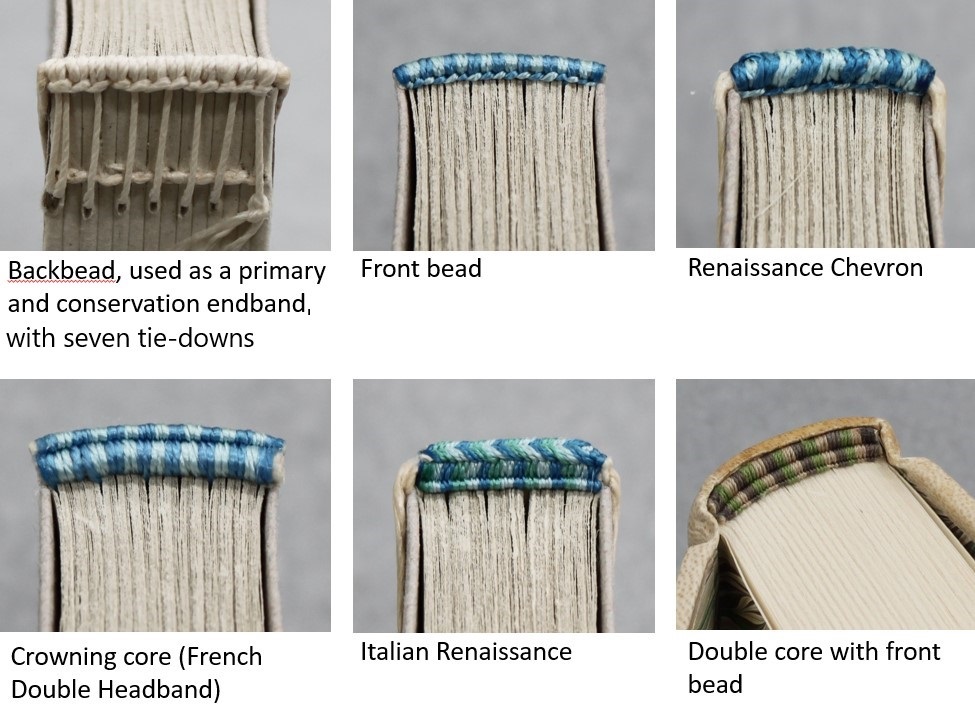

Endbands may consist of more than one core and there are various techniques of wrapping the thread. In the finest bindings, endbands had elaborate designs and multiple tie-downs. Tie-downs are where the wrapping thread is sewn into the text-block – the more tie-down stations, the more structurally stable. However, these are labour-intensive and as time was money, in cheaper bindings you’ll sometimes find an endband tied down just three times. The cheapest bindings had no endbands at all.

By the nineteenth century, endbands were more often ‘stuck on’; decorative cloth wrapped around a core to look like a sewn endband, and adhered to the spine. These were cheap to make in great lengths and cut to size as required. They serve little structural service but could often be very decorative and made to match the text-block edge decoration.

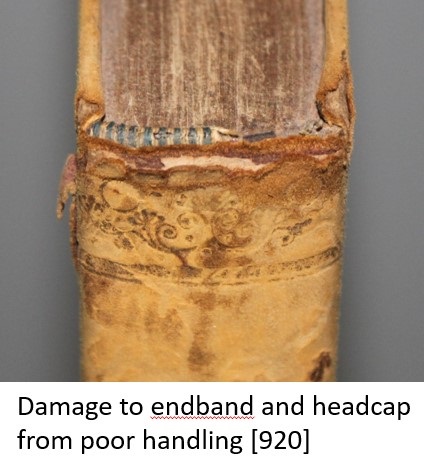

Endbands are commonly missing from the head of a book as they’re often used (incorrectly!) to pull a binding off a shelf. When repairing a book where the endbands are missing, it is sometimes possible to find the remains of the tie-downs still attached to the spine, and from this evidence a conservator or bookbinder can recreate them in the same colours originally used.

The next time you find yourself in a library or amongst old books, take some time to look at the endbands and see what they can tell you about the age and perceived importance of the book when it was bound, as well as the skill of the binder who made it. You might even be tempted to make your own!

I have found all the articles concerning book-binding most interesting and very well illustrated.Takes me back to tying headbands (only very simple ones) at night school in Twickenham where there were professionals in the Printing Dept. who were very patient with us. Sorry I don’t live in Dorchester for I would be enrolling as a volunteer for basic work.

This article is really interesting for understanding development of endband through the history. Thank you for this great information.

I wish someone would actually show how to stitch a backbead endband. The internet says nothing about how to do it!