Burial registers are an incredibly useful resource for those researching family history. Most entries record the name, age and place of abode of the person who has died, but sometimes extra notes are included in the margins. This is the third of three blogs about burial registers, you can read part one here, and part two here!

The views of the Vicar

Some of the notes reflect the views of the rectors, either of the character of those who had died or the circumstances of their death. It is often noted if those who died had served the church, were members of the vicars family or had worked for the rector as a gardener or servant.

There is an indignant note next to the burial entry of 79 year old Anne Trevett in Litton Cheney in 1834. It was written by the Rector, James S Cox, and records that upon her death

‘no less than £21. 14s. 6d. was found in her possession, though she had been on the Parish books for upward of 15 years’

This was the equivalent of around £2150 pounds in today’s money.

The cause of death is noted for all entries on several pages of the Powerstock burial register. Included on these pages is the burial of Benjamin Legg who died in 1862 and in the entry in the column where the vicar has recorded the cause of death he has written ‘Probably worn out by drinking and hard living’. Benjamin also appears in our prison records for 1853 charged with vagrancy and abandoning his family to be supported by the parish, for which he was imprisoned for one month. The family who he abandoned were his wife, Mary, and his five children. Three of whom were deaf and dumb from birth.

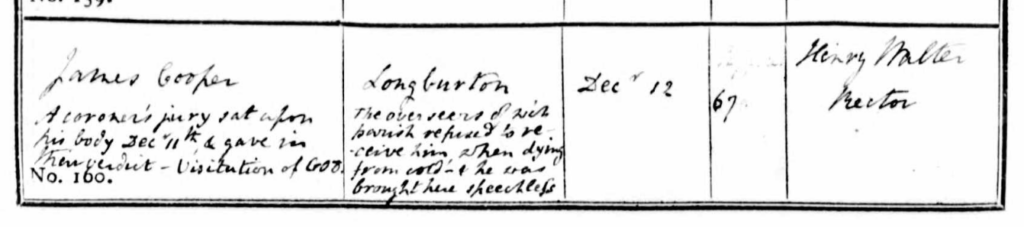

Other entries show more sympathy. Ann Barnes, also from Powerstock, is noted to have died ‘in distressing filth and poverty’ in 1857 and James Cooper of Longburton was buried at Hazelbury Bryan after

‘The overseers of Longburton parish refused to receive him when he was dying of cold and he was brought to the parish of Hazelbury Bryan speechless’.

It isn’t clear whether the last word in this sentence describes the state of James when he arrived in Hazelbury Bryan or how the vicar felt on hearing the circumstances of his death!

Military

Many old soldiers have notes about their military careers included next to their burial entries. A wayfaring man commonly called ‘French Peter’ who is described as ‘very old’ was buried at Fifehead Magdalen in 1864 and was supposed to be a deserter from the French army at Waterloo and in 1915 the burial entry of Robert Ivor Perham records that he had returned to his home from Australia to fight for his country in the First World War.

John Willdin, aged 81, was buried in Broadwindsor in 1820 and had declared that he was a soldier at Sint Eustasius, a Dutch island captured by the British in 1781 by naval forces commanded by General John Vaughan and Admiral George Rodney. The battle was infamous because the commanders were accused of neglecting their military duties in the interest of taking loot. The note in the register states that Willdin never got his prize money.

Daniel Rose died in the workhouse at Cerne Abbas in 1840. He was apparently on of only 33 survivors from his regiment who fought at the Battle of Bunker Hill in Massachusets during the American War of Independence. The battle took place in 1755 and, although the British were successful in taking the hill after the Americans ran out of ammunition, British losses were far higher than those amongst their enemies.

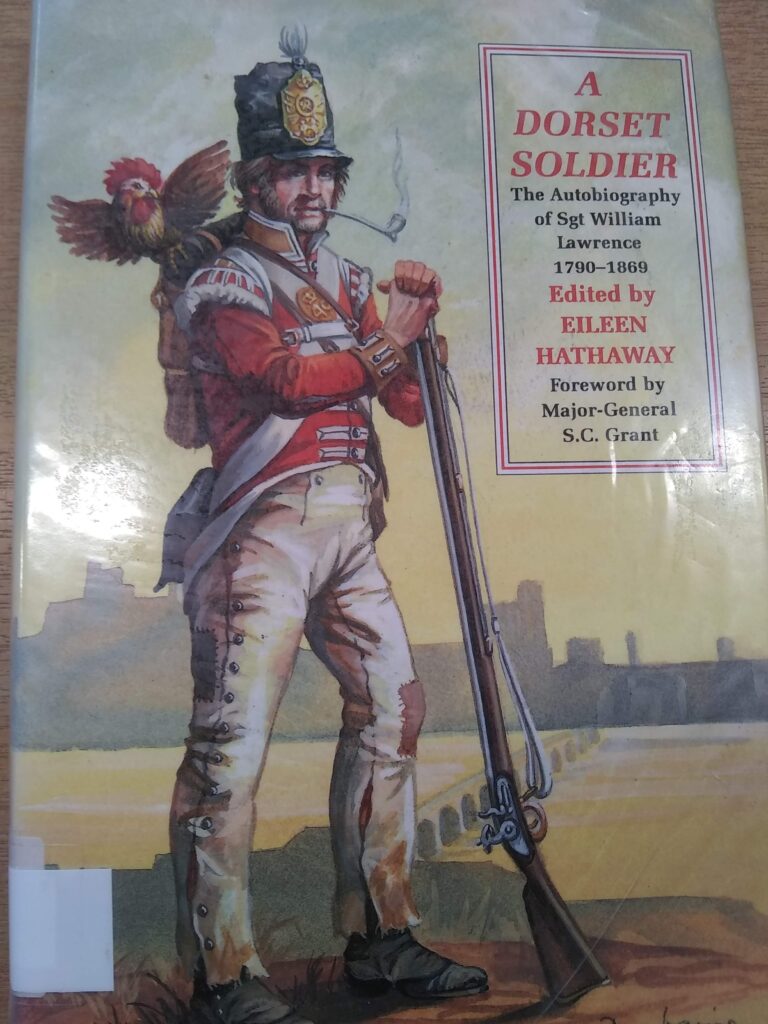

Sergeant William Lawrence served in the 49th foot in the Peninsular war and in Waterloo and his burial entry records he was under fire at nearly every engagement in the war and earned the Waterloo Medal and Peninsualr Medal with 10 clasps. In his later life he wrote down his memories of the war and we hold a copy of these in a book in our reference library. He was buried in Studland in 1869.

It does have to be remembered are written by a vicar, usually many years after these conflicts took place, and they may not always be accurate. William Fendall was buried in Child Okeford in 1888. Next to the entry is a note that says his horse was killed with the last bullet fired in the Crimean War, but is this interesting tale true? It seems unlikely as Fendall would have been 60 at the start of the Crimean War. He was definitely a soldier, but in the 1851 census and on his daughter’s marriage certificate from 1855 he is described as ‘Late Lieutenant Colonel in Her Majesty’s 4th Dragoons’, which suggests he had retired long before the end of the Crimean War in 1856. It is possible that he donated a horse to the regiment, that went to the Crimea without him, or perhaps the vicar who wrote the note got confused and the horse was killed at the end of a different conflict, or maybe it was just a soldier’s tall tale. We will probably never know.

Other notes

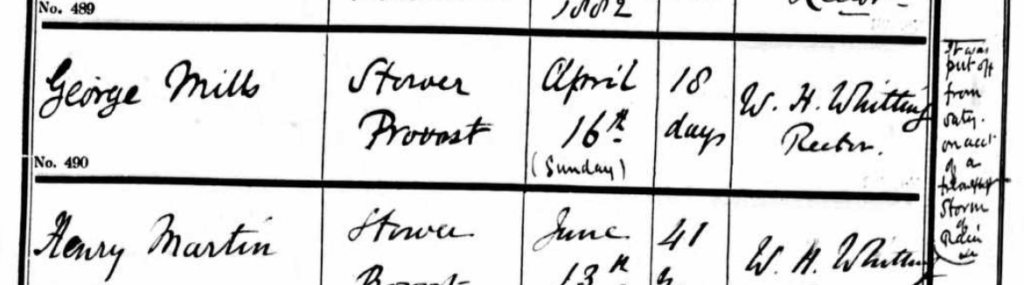

Not all notes in the registers are about the person who was buried. There are several notes about the funerals, whether this be a record that they were delayed by bad weather or the fact that the church bell was broken whilst being tolled for a death because the Sexton had tied the bell rope to the clapper.

Some notes are not linked to any of the burials, such as three notes on a double page from the Winterbourne Whitchurch register for the years 1866 and 1867, which record a very eventful time for that church.

The first note from January 11th 1866 records that there was a great storm of wind and snow that much injured the old yew trees in the church.

The second note describes the replacing of the bells in the church, one of which had cracked in 1840. The note describes how

‘They were rolled by wooden levers and rollers through the church and were hoisted with some difficulty through the Belfry and Bellchamber floors’

Finally there is a note that in March 1867 the organ was destroyed and the nave roof very much injured when a charcoal burner put to dry the organ at the west end started a fire. The night was calm, but it wasn’t until 10pm that the fire was put out with much difficulty.

The Vicar must have been wondering what could go wrong next, but there are no notes like this on later pages so either there was no more damage to the church or the vicar stopped recording it in the burial register!

—

We hope that we have shown what a rich source of information some record sets can be! What strange things have you found whilst searching parish registers? Let us know in the comments below!

Thank you I loved the 3 part blog on the burial register’s. Brilil.ant