Public enquiries often draw our attention to collections we haven’t focused on before. Last year, we received a request to copy a selection of letters to the Blandford Overseers of the Poor, asking for parish relief. This is a fascinating record of those in a difficult position in the past, which we’ll take a closer look at in this blog.

What was poor relief?

But first, let’s work out the basics. Poor relief in supported provided by the local parish to those who were unable to support themselves. Generally, this was through the supplement of wages, but could also include the provision of food, clothing, or accommodation. Until the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, this system was managed individually by each parish, and it was up to the churchwarden and the overseer of the poor to decide how poor relief was implemented.

Inequal rulings

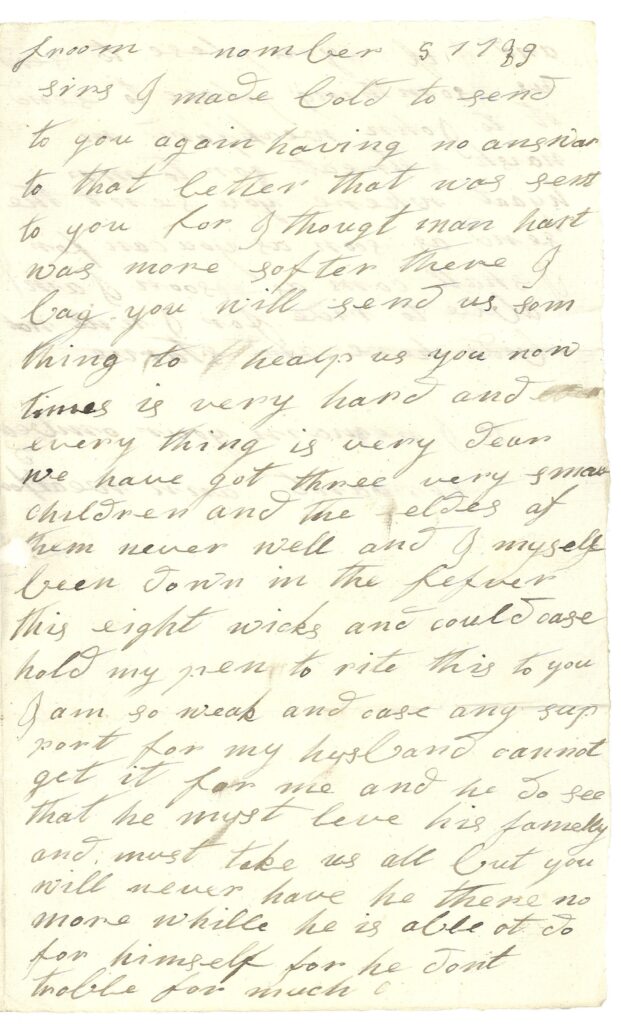

This leads to disparate approaches to caring for those in poverty. Each overseer of the poor would make a distinction between the “deserving poor” and the “idle”. The ill, elderly, and orphaned were considered to be worthy of parish support, but those that were able to work and chose not to were labelled “idle”, and applications for relief were denied. Obviously, this objective system could quickly lead into an abuse of power – local grudges, recent marriages, or large parish donations might swing an unscrupulous overseer, whilst some could be over-zealous in their denial of care. Anne Weakford, an invalided mother of three young children, wrote to the parish following a denied application:

“I thougt man hart was more softer there I beg you will send us som thing to healp us”.

Why poor relief?

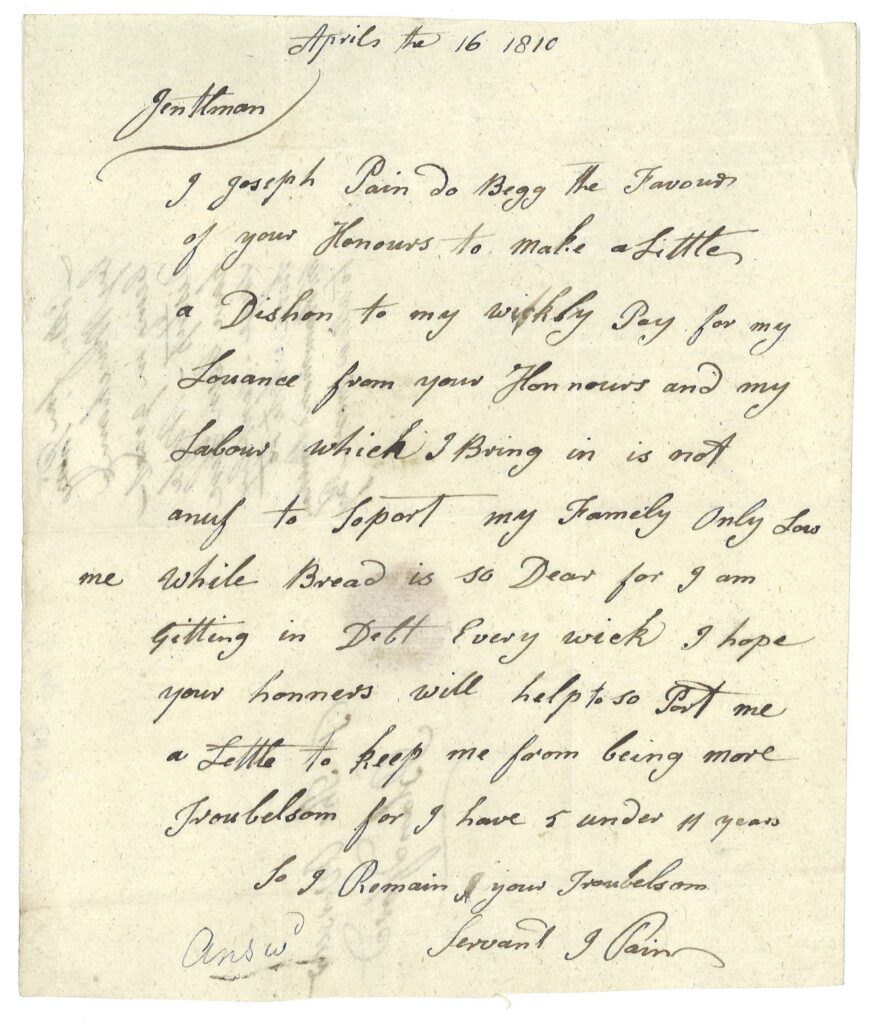

Among the letters to Blandford parish, there are many reasons why parishioners needed to apply for support. The most common was that they were unable to work as a result of injury or illness:

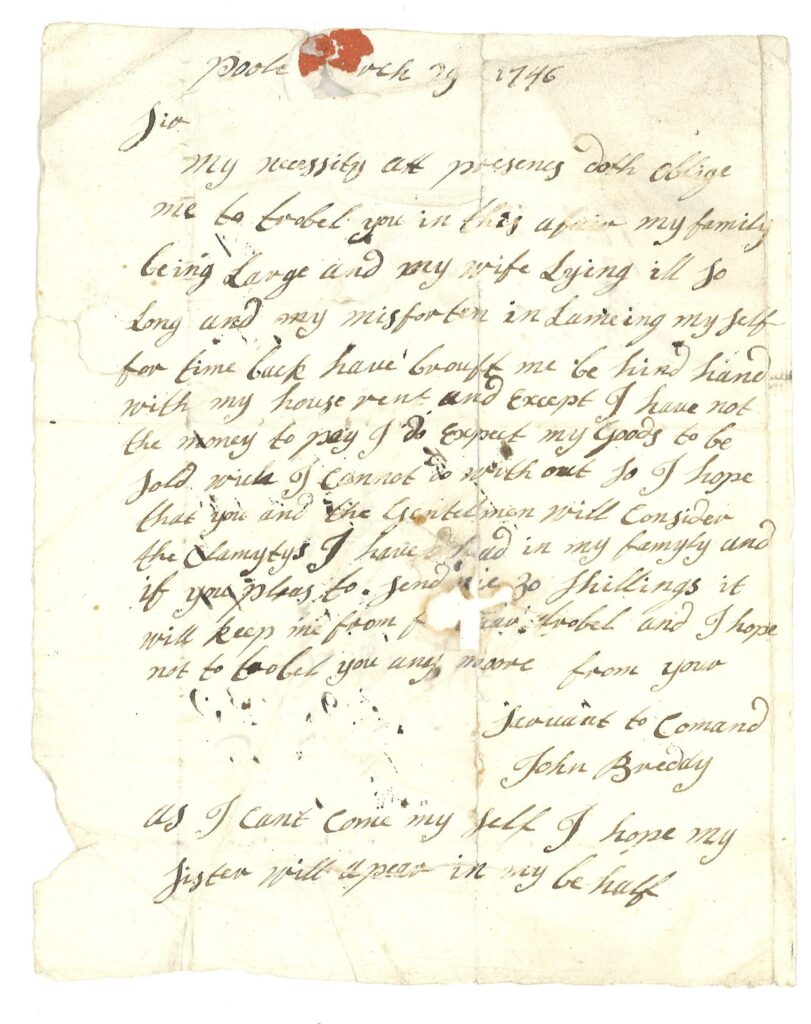

“my family being Large and my wife Lying ill so Long and my misfortune in Lameing myself … have brought me be hind hand with my house rent … Except I have not the money to pay”

– John Breday, 25 March 1746

Others wrote that they couldn’t find enough work, especially during the winter or when the weather was bad.

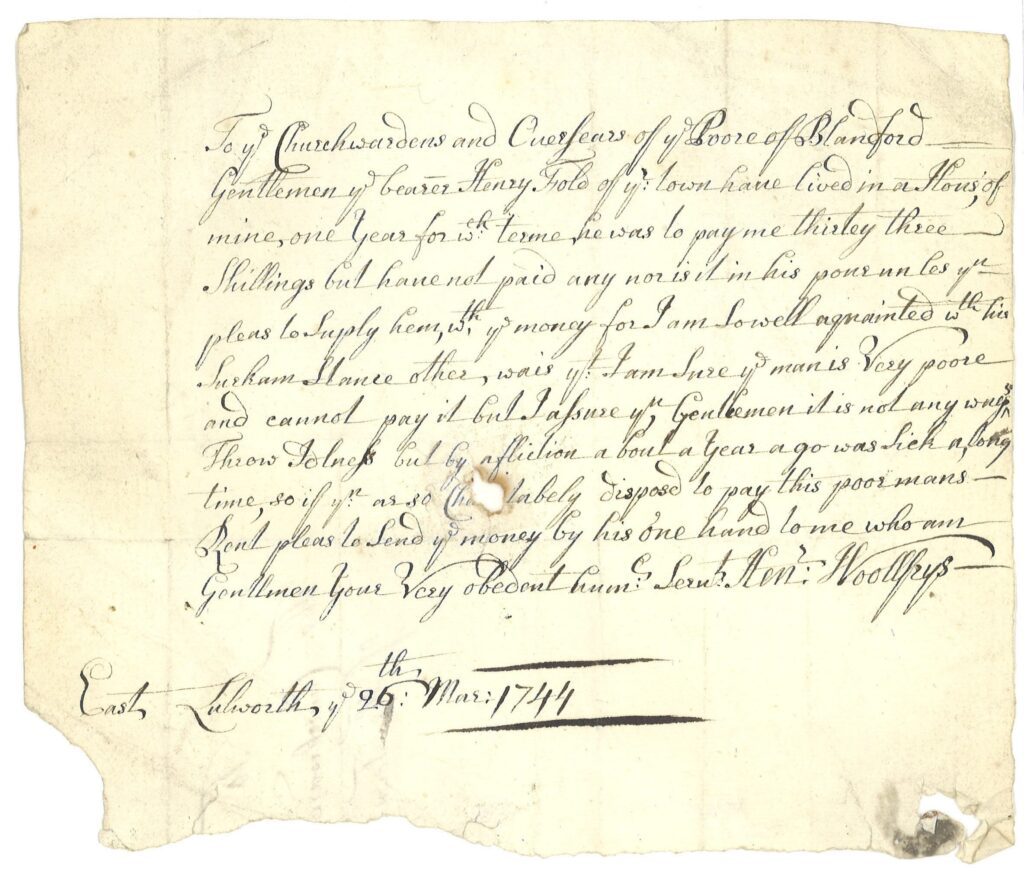

Those who couldn’t write had to ask others to appeal for them. Henry Woolfrys wrote on behalf of his tenant Henry Fold in 1744, and included a character assessment to support his friend’s claim:

“but I assure you Gentlemen it is not any ways Throw Jolness but by affliction a bout a Year ago … if your as so Charitablely disposed to pay this poor mans Rent pleas to Send your money by his one hand to me”

Travelling for work

Poor relief was provided by a person’s “home” parish – that is, the parish they were born and raised in. Many letters in the Blandford overseer’s collection are from other parishes in Dorset, or even as far afield as Bristol and London. Christian Horlock of Golden Lane, London, wrote to his home parish of Blandford in 1780:

“I am sorey that necessity obliges me to Trouble you with these [lines]… letting him kno the destressed situation me and my Family should be in if we had not some Relief from the Parish for I am so very lame that I cannot do anything to help soporte my Family”.

Those whose wages couldn’t cover their needs, or who had been temporarily invalided, might receive wage relief from the parish instead. However, if those who couldn’t work would have to return to their parish, where they would be accommodated in either an almshouse or workhouse. Parents who couldn’t support their children had to decide between leaving their family to return to the workhouse themselves, or sending the children instead:

“if you will not relive us we must send the children home for we are not able to manetan them without some help”

– Mrs Mullet, Bristol

—

These records show us how the local community and government tried to support those in need. It also highlights the lengths people will go to care for themselves. None of the applications are casual – each one is written from a desperate position where the author is fighting for themselves. As Anne Weakford wrote,

“I shall come as soon as I am able to ride for I will not bide here and starve.”

If you want to read more, a previous blog looked at the implications of the Poor Law system for one family, as discovered from one letter.

The letter was the transcripion “it is not any ways Throw Jolness but by affliction” actually reads Idlness, rather than Jolness. The upper stroke of the ‘d’ bend to the left, over the ‘I’, as can be seen for other ‘d’s in the letter.