A recent set of purchases at auction throw new light on our understanding on one of the most prominent figures in Dorset’s history. The purchases were funded by Friends of the National Libraries with a contribution from Dorset Archives Trust. DHC was delighted to be able to acquire these items which will now form part of the permanent public collection and is extremely grateful for the financial support that was made available by both these charities.

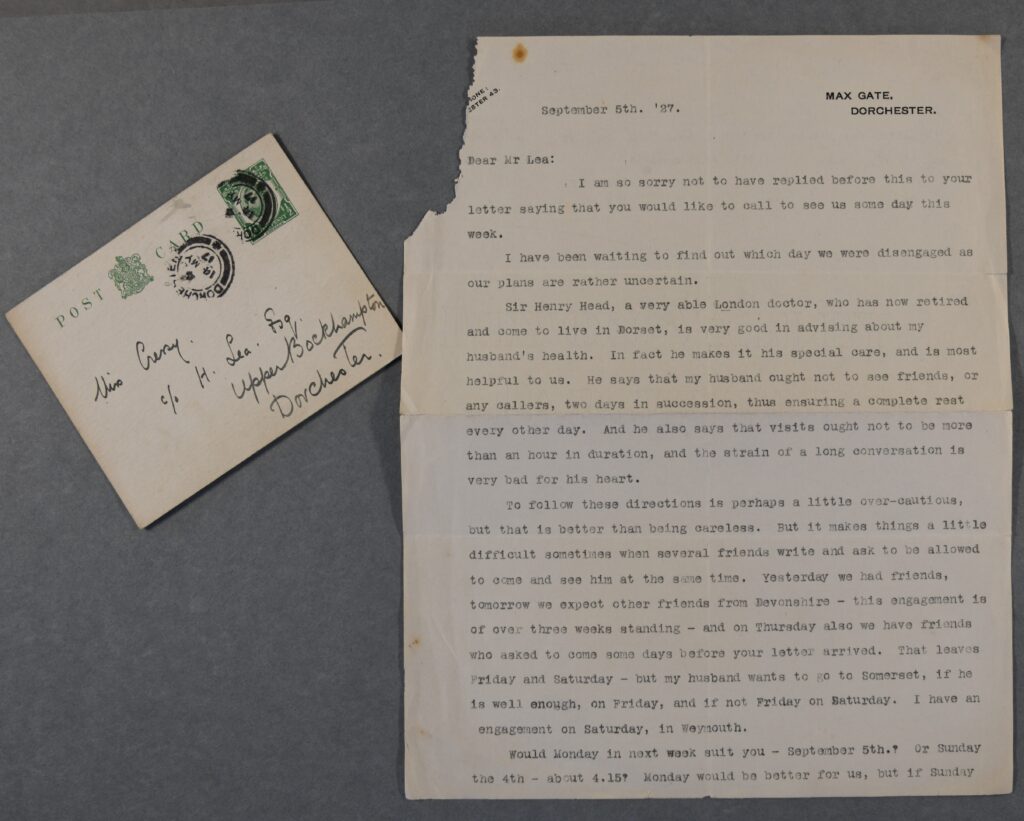

The first of the items in question is a letter written in September 1927 by Florence Hardy to a Mr. Lea of Bockhampton. In it, she describes the deteriorating health of her husband Thomas. She tells of a ‘very able London Doctor’ Sir Henry Head who had retired to Dorset and who was being particularly attentive to Hardy. Sir Henry had advised that Hardy

‘ought not to see friends or any callers, two days in succession…[as]…the strain of a long conversation is very bad for his heart’.

Florence then goes on to list the upcoming visitors and social engagements that the couple anticipated which appears to somewhat fly in the face of the medical advice proffered by Sir Henry. The letter is poignant in that it was written a little over four months before Hardy’s death on 14 January 1928 of a cardiac-related condition.

—

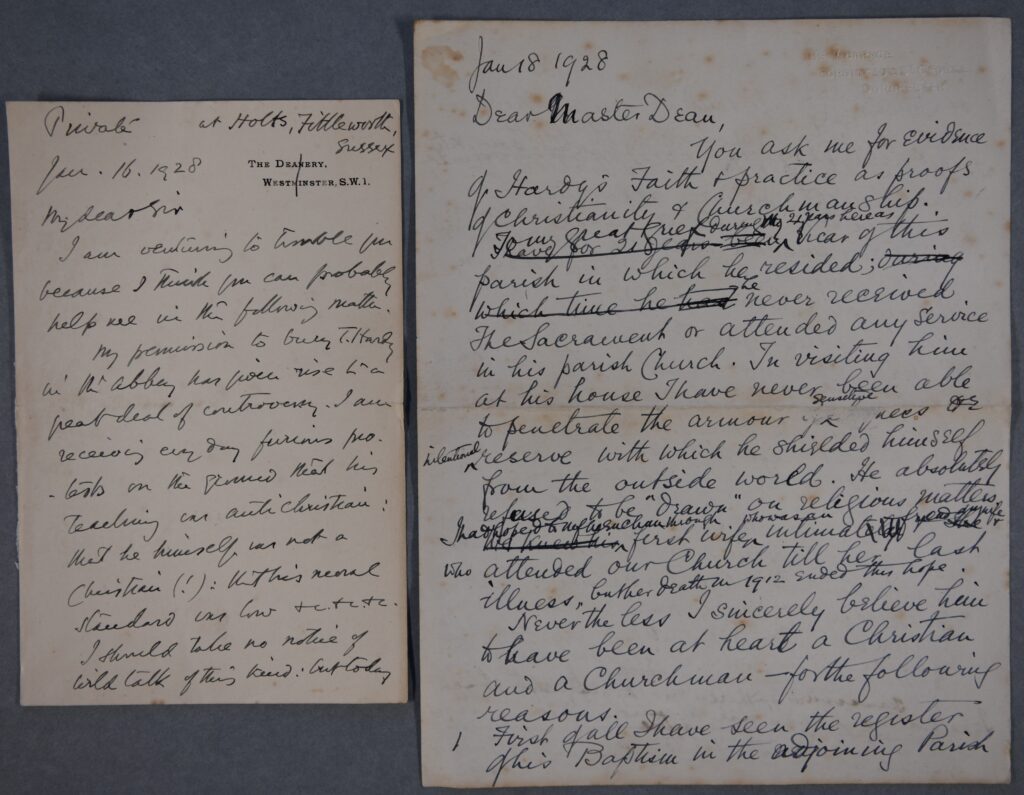

The second item is a pair of Thomas Hardy-related letters dated immediately after the author’s death. The exchange concerns the arrangements for the interment of the author’s ashes at Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey. The Dean of Westminster writes to the Vicar of Fordingdon, the Reverend Richard Grosvenor Bartelot that his decision to permit Hardy’s burial

‘has given rise to a great deal of controversy. I am receiving every day furious protests on the ground that his teaching was anti-Christian and that he himself was not a Christian, that his moral standard was very low, etc.’.

The Dean goes on to say that having previously ignored the criticism, he had now received a letter from the ‘head of a great religious body’ and that he now felt compelled to properly respond to Hardy’s detractors.

The Reverend Bartelot replied that although convinced of Hardy’s essential Christianity, in matters of religion,

‘he had never been able to penetrate the armour’ and that ‘he [Hardy] absolutely refused to be “drawn” on religious matters’.

Bartelot then proceeds to offer six reasons why Hardy (in his opinion) was ‘at heart a Christian and a Churchman’ despite the fact that he had never taken the sacrament or attended services in his own parish church. The justifications quoted by Bartelot focus largely upon charitable acts rather than explicitly religious undertakings. The first of these was given as Hardy’s subscription to

‘the restoration of our church specially allocating his donations towards the abolition of two hideous Tuscan arches erected in 1833 by the Rev H Moule.’

Despite the relative paucity of obvious religious activity, Bartelot points to what he calls ‘the absolute moral rectitude of his [Hardy’s] private life’ as well as his ‘keen interest in church music’.

As we now know, Hardy’s ashes were indeed interred in Westminster Abbey on 16 January 1928. The event was attended by amongst others Prime Minister Ramsay Macdonald, Rudyard Kipling, J. M. Barrie, G. B. Shaw and A. E. Housman. Underscoring Hardy’s undying associations with Dorset, a spadeful of soil, supplied by a local farm labourer Christopher Corbin was sprinkled on the casket.

These letters written about Hardy rather than by him provide fascinating details of the author’s life and the perspectives held on him by others. It is also interesting to note the contentious debate that broke out around Hardy’s religious convictions as the nation mourned the person described by the New York Times in its obituary as the ‘master of English letters’.

What an interesting article. I personally extend a posthumous thanks to Hardy for his keen attention to church renovations in Dorset during his early career. As an historian, I am grateful for the journalistic details he left in relation to St. Andrew’s Church at Lulworth.

Hardy stood in support of St. Andrew’s church recounting its 13th century antiquity after 19th century renovations dramatically changed the fabric. His discussions with the Thackery Turner at Society for Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) were particularly enlightening.

“. . . and it is evident that here was once a building of considerable architectural pretensions, though eighteenth century architects in their efforts of “improvement” considerably marred the beauty of the original design; the tower fortunately remained untouched, as if to put to shame the meanness of more modern innovations on the former beautiful style.”

~Thomas Hardy, 1864