At the time of the First World War 16 nations mobilized over 65 million soldiers; of these 8.5 million were killed, over 21 million were wounded and nearly 8 million were recorded as captured or missing. The First World War brought new, more brutal and more catastrophic methods of warfare and the condition known as ‘shell shock’ became much more commonplace on both sides. In Germany over 600,000 servicemen were treated in military hospitals for nervous diseases, whilst in the UK 80,000 cases of war neurosis were diagnosed. By the end of the conflict approximately 200,000 British veterans were in receipt of pensions for war related nervous disorders. (Data from 1914-1918 Online International Encyclopedia of the First World War)

During the first two years of the conflict, public and political concern was raised about the treatment of returning soldiers suffering from ‘shell shock’ and from what we now call PTSD. The War Office planned to treat men with such conditions in the mental section of Netley Military Hospital near Southampton and allocated an additional 2000 beds in war hospitals. However once these spaces became full servicemen were treated in asylums alongside those classed as ‘pauper lunatics’. This was seen as demeaning and disrespectful to men that had fought for King and Country so the Army Act gave soldiers the special status of ‘Service Class’. These patients were treated differently in the asylums. Higher maintenance charges were paid for by the War Office, not their local parish. The patient received an extra payment of half a crown for extra comforts and were allowed to wear tweed suits to distinguish themselves from the pauper patients. They also had financial support when ‘on trial leave’ from the asylum and most importantly they received a war disability pension.

Such measures sound very fair, practical and beneficial but Dorset County Asylum records held at DHC show that it was not easy to gain such classification, especially if the symptoms manifested themselves a few years after the end of the war.

Here are the contrasting stories of three such soldiers whose records form part of the Herrison Collection.

DANIEL PATRICK MOORE, age 36 and married, was admitted to Herrison on 4th May 1918 into pauper class but was transferred into Service Class by June of the same year. He had come from Dykebar War Hospital in Paisley and was treated and discharged on 24 April 1919.

—

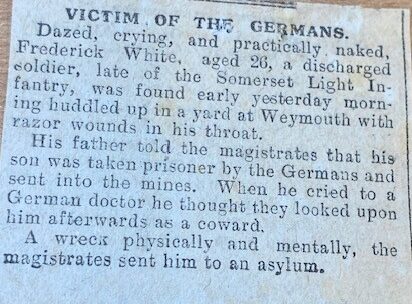

FREDERICK JAMES WHITE was admitted to the asylum on 2ndApril 1919. He was age 26, single and described as a discharged soldier. He presented as suicidal and the supposed cause of his condition was ‘War prisoner in Germany’. (NG-HH/CMR/4/32/7036)

Unfortunately Frederick was not awarded the classification of Service class as his condition was not considered to be as a result of his war service. He died at the asylum as a pauper lunatic two years later.

—

ALFRED MONTAGUE RYALL, age 24 was admitted on 14thMarch 1923. He was single and lived on the family farm at Cann near Shaftesbury. He had been unwell for some time and had previously received treatment at the asylum in 1921. The supposed cause of his illness on his admission papers was ‘nervous debility probably due to military service.’ Alfred suffered from delusions, violent outbursts and stated that he had ‘many terrible ideas come into his head’. However he was admitted as a pauper patient without any of the benefits of Service Class status.

Ten days after his admission a letter from the Shaftesbury Union set out their refusal to pay Alfred’s maintenance stating

‘this is an ex-service man, and from the opinions expressed by members of my Board, who are personally acquainted with the man…it is clear to the board that this man’s mental condition is solely due, and aggravated by, his military service’.

They sent a copy of the letter to the Minister of Pensions requesting that ‘they should treat the man as a Service Patient’ (NG-HH/CMR/4/33/1571).

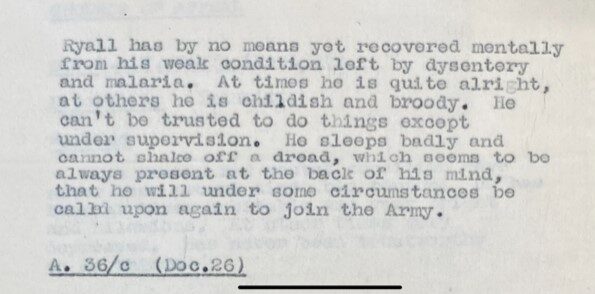

This was rejected by the Ministry of Pensions arguing that his disability was not caused by serving in the war, but rather by pre-existing feeblemindedness/dementia. Alfred’s case then went to a Pensions Appeal Tribunal, the papers of which are found amongst his admission papers. These documents summarize a troubled war service joining the RASC in Europe in 1916 and later serving in East and South Africa. Alfred suffered from malaria, dysentery and neurasthenia (fatigue and anxiety). He spent much time in and out of medical facilities during the war and was finally invalided to England in February 1918.

Alfred’s parents described his condition to the Appeals Tribunal stating:

The grounds for appeal provided evidence from Alfred’s pre-enlistment doctor, a neighbour and a property agent that had known him for many years. All these witnesses contested that Alfred’s manner and health was dramatically altered as a result of going to war.

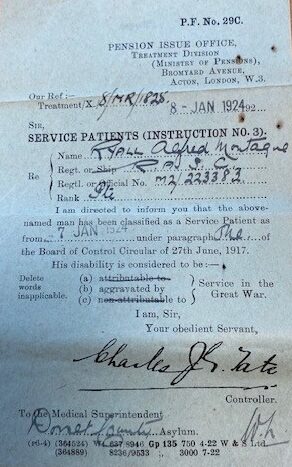

Whilst the tribunal documents do not state the official outcome of the appeal, I did find a small but not insignificant piece of paper tucked away amongst Alfred’s papers showing that from 7thJan 1924. Alfred was at last classed as a Service patient and thereby entitled to a War pension.

By 19 January 1924 Alfred is discharged ‘on trial’ back into the care of his parents and is recovered by March of the same year.

The reluctance of the authorities to automatically admit Alfred into Service Class when he first entered the asylum in 1923, in comparison to the treatment of Daniel Moore admitted in 1918, could be explained by Peter Barham, author of Forgotten Lunatics of the Great War. In his book he highlights a trend in the latter years of the war and beyond. He believes that the Ministry of Pensions wanted to ‘roll back pension awards’ as the country faced the austerity of the 1920’s. He states that ‘less than 150 servicemen admitted to asylums were rejected classification as Service patients in 1918, but by the mid 1920’s over 60% were being refused’.

At least Alfred eventually got the support he so rightly deserved.

—

You can discover more about shell shock through the work of the Imperial War Museum.

—

This was a guest blog written for Dorset History Centre by Jane Ashenden, a volunteer at DHC. If you would like to promote your local community event, or tell us about some research you have been undertaking, please get in touch: archives@dorsetcouncil.gov.uk

Great research Jane. The ongoing issue of support for ex-service people can be observed in records following other conflicts such as the Napoleonic Wars and seen in post WW1 workhouse records.

Thanks for drawing these individuals to our attention in such a concise context.