Our new Reprographics Assistant Tara has been getting her hands on a collection of glass plates, and has been fascinated by what she has found…

—

When I started my job here, I learned of a collection of glass plates that had been donated to DHC and that were part way through being digitised. Having a strong personal interest in glass plates I was keen to take up the mantle of completing the digitisation.

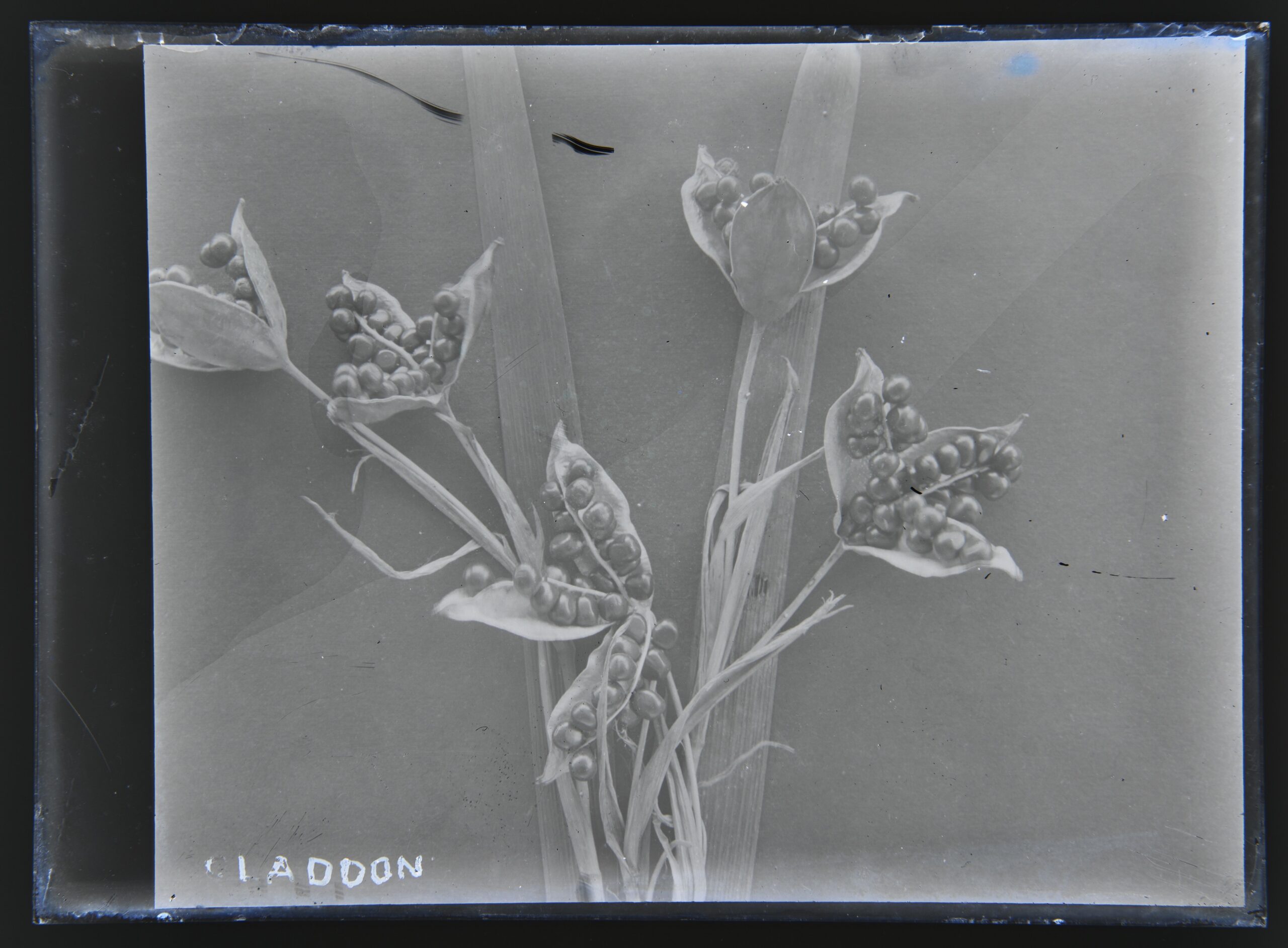

The plates date around the early 1900’s, having found one with the date of 1918 written on it. There is a huge variety of subject matter, from formal group photographs of soldiers to small family groups and individuals, to dog portraits, and landscape photographs of the area, with close ups of local flora.

There is a mystery surrounding this collection, as they were brought to us by a gentleman who told me that had been rescued form the skip by a young builder who had been working on the roof of the Black Dog Inn, Broadmayne, where they had been stored in the loft space. The photographer is unknown. There is a possible link in one of the portraits to Gertrude Bugler, who was an actress in Thomas Hardy’s plays, as there is a striking similarity. The girl in the glass plate portrait appears quite young and could possibly even have been the grandmother of Gertrude.

Some of the plates are in superb conditions, whilst others have suffered some damage through age. The patina of these classic plates is beautiful, the softness of tones, the gentle silvering, and the sheer fragility of the thin glass make them a joy to handle (with gloves!), to hold a piece of history in the hand. Many Victorians believed that having a photograph made of them would steal their soul. They did not understand the technology that allowed a likeness of them to be captured on a glass plate – they felt the camera must be stealing a part of their souls to do this.

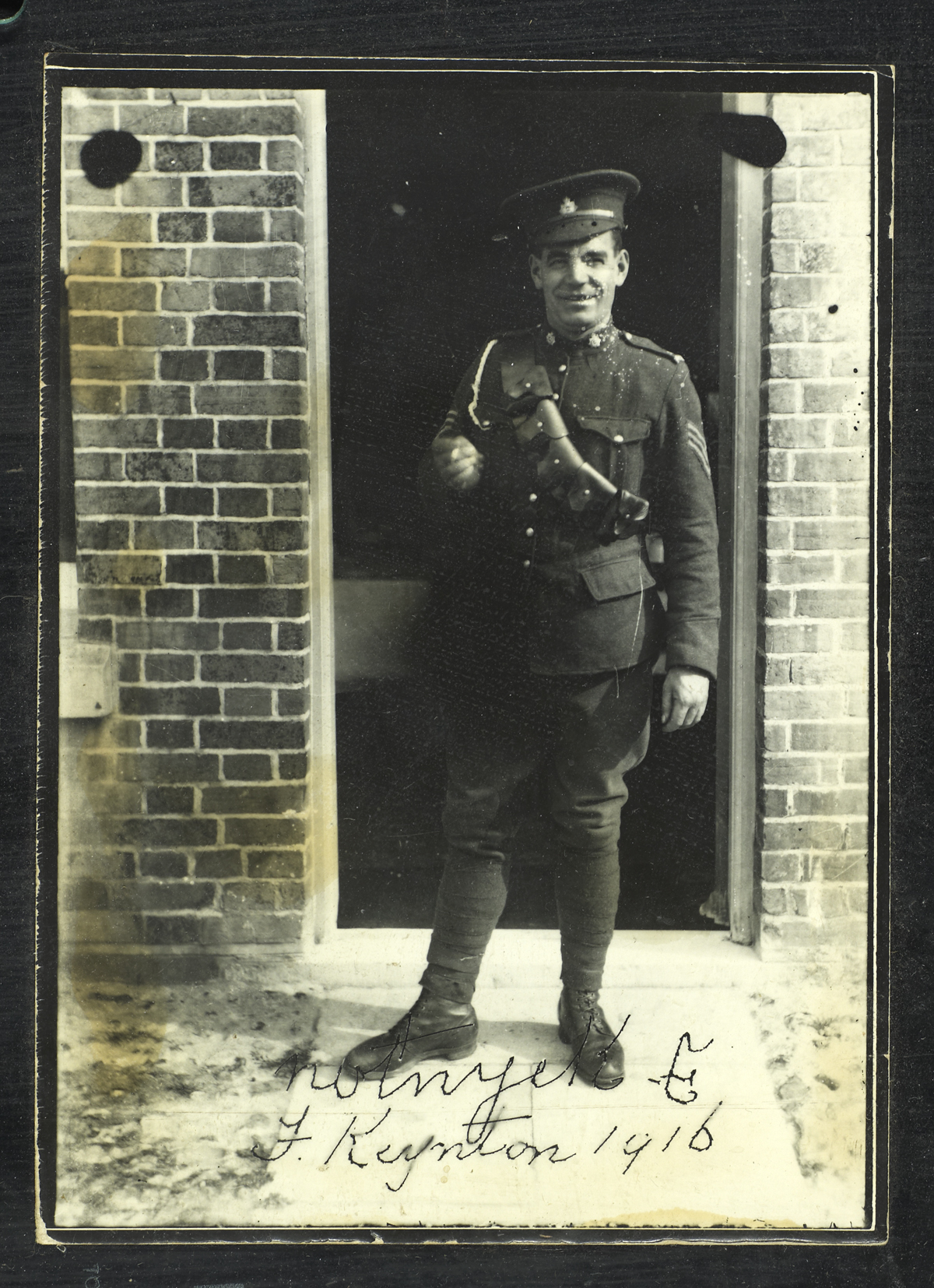

This collection is intriguing, in that we also have another two boxes of photographs and plates from around the same time, also from the Black Dog Inn. The collection I have been digitising numbers 100 with a further set of approximately 60, and approximately 70 black & white photographs. One of the B&W photographs has the name “F Keynton 1916” inscribed onto it. He appears to have been a Sargeant Major. Does anyone know who he might be?

I wonder how it came to be that so many photographs were taken in and around a small village in the early 20th Century at a time when photography was not widely accessible, and one would have to have the means and knowledge to make these photographs. The glass plates are most likely to be dry plates, in which a thin piece of glass was coated in a silver gelatin emulsion. These dry plates enable photographers to have ready made plates meaning they did not need to bring the darkroom with them, unlike the era of wet plate, whereby photographers would have to have all their chemicals and a portable darkroom with them and would need to coat a plate and expose it within 15 minutes whilst it was still wet. I wonder if anyone has any knowledge of the origins of these plates, or knows who the photographer may have been? If you can help to shed some light on them, please do get in contact.

—

These glass plates have piqued our interest and one of our volunteers has done some more digging into the story of Frederick Keynton and the Black Dog Inn, and you can read more about them both in a two-part blog:

The 1921 Census records Frederick and Emily Keynton (plus a few others) living at the Black Dog in Broadmayne. Frederick was 57, and described as a licensed victualler.

Frederick George Keynton was born at Swindon in 1864 and married Emily Jane Whicker at Holy Trinity, Weymouth on the 24 December 1887. He died in 1938, aged 73, and was buried at Broadmayne. Frederick’s father George, who died in 1895, was landlord of the Black Dog before him. According to earlier census returns, Frederick previously lived in Wyke Regis, working as a railway fitter and as an engineer at a torpedo works.

However, I can find no record of a Frederick Keynton serving in the forces during the First World War.

Hi Michael – thank-you for your reply, and watch this space! We have a couple of blogs relating to Frederick coming out in the next couple of weeks!

Re Frederick Keynton

He would have been 52 in 1916 – surely too old to have served in WW1?

Could this have been his son?

Hi Carol – thanks for your comment. As you say, Frederick was too old for conscription in WW1. However, we have evidence of him serving as a volunteer in the Dorset Militia and, as war approached, a Supernumerary Instructor. His previous experience with coastal ordinance and at Whiteheads Torpedo factory would have meant he had plenty of knowledge to pass on. So, I believe we are seeing Frederick in his uniform as an Instructor – Dorset’s Volunteer Coastal Gunners were a long-lasting force and a book is dedicated to their history. Frederick and his wife had no ‘natural’ children, but informally adopted a neighbour’s son. Do check out the next two blogs in this series for the whole story.

I am fascinated by glass plates. The ones I sell are quite different to these!

Do you have any more of the glass plates other than the ones in these three blogs?

Please do let me know if they go on display anywhere. Thank you.

Kind regards

Anna K

Hi Anna, thanks for your comment. We have a variety of glass-plate records here at Dorset History Centre: https://archive-catalogue.dorsetcouncil.gov.uk/search/all:records/0_50/all/score_desc/glass%20plate. These vary in quality, and can be quite fragile; and therefore we don’t typically have them on display, preferring to use surrogate copies instead to help protect the originals. There are also concerns about the effect of light on the plates over a period of time which we have to be aware of when considering them for displays. If you would like to know more about what we hold, please get in touch with us: archives@dorsetcouncil.gov.uk and one of the team can help further.